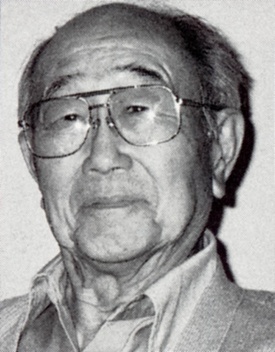

Harold Ikemura loves to tell stories about his years in the fishing fleet. At 83, he recalls with astonishing detail the particulars of his long life and of his years at sea. “I love fishing,” he says with delight.

As a teenager, Ikemura went trout fishing along the San Gabriel River with the sons of a prominent Pasadena Japanese American family. Dr. Takejiro Itow, one of the founders of the Japanese hospital in Los Angeles, also had a daughter, Sumi, she eventually became Ikemura’s wife.

Ikemura, who was born in Riverside and grew up in Hollywood, California, didn’t care much for his studies at UCLA. But he had a hot rod and loved machinery, so he applied to a diesel school. The school turned Ikemura down. They promised jobs to all their graduates, and couldn’t guarantee a job to the son of a Japanese gardner. Ikemura was finally accepted after he managed to convince the school that he wouldn’t depend on them to supply him with a job.

After Ikemura graduated from the diesel school, Dr. Itow, who had a second office in the Japanese fishing community on Terminal Island, suggested to Ikemura that fisherman could make good money. “Oh boy,” says Ikemura. “Right now I went right down to Terminal Island and the Japanese Fisherman’s Association.”

Eventually Ikemura landed a job on a fishing boat. On his first boat, the Panama, he proved his mechanical abilities. “When I saw the engine, I told him (the owner) that the water circulation outlet was not correct. He remarked something like ‘what do you know about anything?’ but when we got to San Diego Bay, something went ‘ping’ and the cylinder head cracked.” On another trip, Ikemura was aboard the San Lucas when it began to sink in the Gulf of Mexico. Ikemura and his shipmates were able to reach Cabo San Lucas in a small boat skiff.

Fishermen hooking tuna on the fishing boat, "San Lucas", at sea. Tuna caught by fisherman are in the large hold behind them. Terminal Island, CA, c 1930s. (Gift of Dentaro Tani, Japanese American National Museum [94.191.1])

Ikemura’s knowledge of engines meant that he soon became an engineer, and then a chief on a variety of fishing boats. A chief is the person responsible, says Ikemura, “for keeping the boat alive. The chief was responsible for all the boat’s mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and refrigeration systems—the skipper figured out where the boat should go and pointed it at the fish.”

Ikemura was about to become chief on a brand new boat out of San Diego when the war broke out. “And that was that,” he says. “Of course the government confiscated all the good boats for their use. Being a citizen, I thought I was going to be able to go on fishing. But I found out different.”

Ikemura and his wife were first incarcerated in Santa Anita, then at Poston, Arizona where their first son was born. They transferred to Gila River, Arizona in order to be near his wife’s family. Ikemura was drafted while in the camp at Gila River, Arizona and after basic training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, was transferred to Minneapolis and served in the 442nd RCT before being sent to Japan as part of the occupation army.

The Japanese presence in the west coast fishing industry was virtually destroyed by the effects of wartime incarceration. Few of the first-generation Japanese fishermen returned to fishing, although some Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) came back to fish out of San Diego. On his return from Japan, Ikemura and his wife moved to Coronado where their next two sons were born and where they lived until 1952 when they built their present home in San Diego. Ikemura got a job as chief on the Santa Barbara for a couple of years and then joined skipper Dan Marks as a member of the crew of the South Coast.

“I got on that boat,” Ikemura says, “and it was a little heavy, and I thought uh-oh, by this time next year I’ll be looking for a new job. But they hated for you to quit after one trip, and there was 4% available on the boat. So they gave me that 4% and raised my wages to a share and three quarters and I stayed. Fishing was going bad and so forth, but for some reason our cannery kept operating. One year all the canneries quit operating but our cannery kept operating with just two boats. When the cannery sold the boat, I bought another 10% and I had 14% and stayed on that boat for twenty-one years. Of course I had offers from other boats and better jobs, but Dan Marks was a very good skipper and we never had one bad trip.”

Ikemura bought a partnership in a new 550 ton capacity tuna seiner in 1970, but it was never quite the same. Ikemura shows a visitor a large framed photograph of the South Coast. “The romance sort of went out of fishing when we converted the South Coast to seining in 1965,” he says. When they were fishing with poles that big fish would go pitter pat on the deck and the whole crew would get excited.”

He looks at the wall of photographs, focusing on a picture of three fishermen struggling to land a tuna. “I still go trout fishing when I can,” he says. “I really love to fish.”

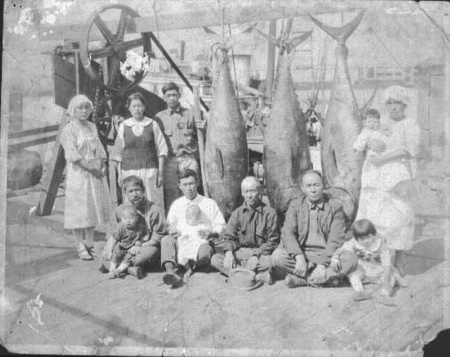

Crew of "The Patricia" posing with catch of tuna. Three large tuna hanging from beam. Morro Bay, CA, ca. 1925. (Gift of the Shimazu Family, Japanese American National Museum [92.130.4])

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Spring 1997.

© 1997 Japanese American National Museum