Between 1942 and 1945, 1,771 Japanese nationals and their descendants in Peru were deported to the United States. The Peruvian government, allied with that of the U.S. during World War II, authorized the capture of “potentially dangerous enemies”—Japanese, Germans, and Italians—to be sent to concentration camps in the U.S.

One of the deportees was Mitsuya Higa. He was 12 or 13 years old when his uncle Rensuke, owner of a chicha factory, decided to surrender himself to the authorities. [Note from the translator: “chicha” is a Peruvian beverage derived from maize.] He had been in hiding in a cabin surrounded by a plantain plantation in a plot of land owned by a Japanese family, near the Baquíjano y Carrillo cemetery in the city of Callao, adjacent to Lima. Dogs watched over the place.

The risk that he would be found was minuscule. But the police, who had been searching for him, made him a proposal through his family. That in turn enticed him to abandon his hiding place: if he surrendered, they would allow him to be deported with his wife and children.

Why did he accept the offer? Perhaps because he was fed up with living clandestinely, as if he were a criminal (or was his prosperity in Peru considered a crime?), separated from his family, and he believed that since they were going to be imprisoned in the United States, they would at least remain together.

Rensuke was “lucky” if we compare his case with those of the Japanese who didn’t even have the chance to let family members know they were going to be expelled from the country.

Mitsuya’s parents owned a shop on a street where trucks drove by carrying the imprisoned Japanese to the port of Callao, the point of departure to the United States. When they passed by the establishment, some of the Japanese would throw little pieces of paper at a surprised Mitsuya. “Otosan! Otosan!” they shouted. He would then collect the pieces of paper and run back into the store to hand them to his parents. What had been written on those little pieces of paper? The names and addresses of the wives of those men being transported like cattle. As soon as they finished reading the messages, Mitsuya’s parents would go inform the wives that their husbands had been captured.

Sometimes, desperate Japanese women arrived at the store, holding photos of their husbands, suddenly gone missing, to ask if they had been seen in the passing trucks.

Back to Rensuke: what he didn’t know (how could he have known?) when he decided to leave his hiding place was that—Mitsuya recalls—he would sail aboard the last ship carrying the deportees. The very last one. That shows the randomness of things (or fate).

Rensuke had a son, Rentoku. He and Mitsuya were very close, always playing and running around together.

After Rensuke surrendered himself, his family began preparations for their departure. Rentoku then suggested to his cousin Mitsuya that he travel with them. “We’re going to see the cowboys,” he explained.

Mitsuya was seduced by the “invitation.” The Higa family was going to be sent to a concentration camp in Texas, which for him was the land of the cowboys, whom he admired due to the American movies he enjoyed watching.

One of his heroes was actor Tom Tyler, who was featured in Westerns directed by John Ford, among them Stagecoach. He was going to meet Tom Tyler and other cowboys! “I was happy, thrilled. To me, it was an adventure,” he recalls today, nearly 70 years later.

Rensuke talked to his younger brother Renzo, Mitsuya’s father, asking if he would give permission for his son’s trip. He received his brother’s consent, and right away they began getting Mitsuya ready for the long voyage to Texas.

His parents ordered a suit especially for the occasion, and bought him little crochet slippers. They placed his belongings in a suitcase. Everything was ready for Mitsuya to begin a new life in the land of Tom Tyler.

On the day of the departure, Rensuke stopped by to pick him up, but Mitsuya was unable to accompany his uncle. His mother stopped him from going. While Mitsuya was saying his goodbyes, she put her arms around him and squeezed him tight, as if she wanted to meld as one with her son. “Okasan was hugging me, crying, and she wouldn’t let me go,” he remembers. And thus he forever remained in Peru.

Mitsuya smiles while remembering how naive he used to be. After becoming an adult, he was able to comprehend the tragedy his uncle had to endure, extricated from the country where his children were born and where he had built a new life—the immigrant who lost everything he had amassed after decades of labor and that, at the end of the war, returned with his family to an impoverished and destroyed Okinawa, where all that was left were mouths to feed.

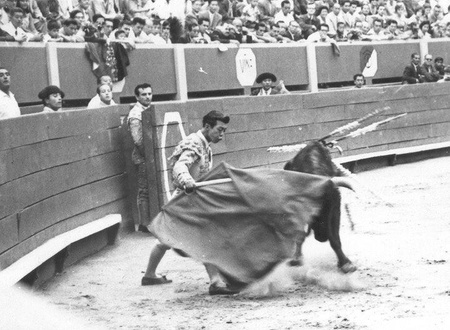

Whatever happened to Rensuke? Mitsuya can’t remember. Or perhaps he prefers not to because he has chosen to keep in his mind the picture of his proud uncle atop a racehorse—the man who took him for the first time to the Plaza de Acho, the oldest bullfighting arena on the American continent, unaware that many years later his nephew would become the first toreador of Japanese ancestry in history.

© 2014 Enrique Higa