After Bryce’s dad, Tameo Kanbara, was released from the prisoner of war camp in 1946, there were only two choices: move east of the Rocky Mountains or to war-torn Japan.

To be sure, the government’s plan was to make sure that Japanese Canadians were dispersed across Canada so as to protect them from whatever imagined threat we represented. Every means possible was used to make sure that a post-war community like there had been in Vancouver never formed again anywhere in Canada.

At the end of WW2, there was absolutely no reason why JCs should have believed anything that the federal or BC government told them. Most had lost all material possessions, including homes and jobs. The most desperate and disillusioned then, perhaps, were the ones who went to war shattered Japan even despite knowing the extent of the destruction and the hardships that survivors were enduring. Burdening those families anymore was a tumultuous decision made at a most catastrophic time: to stay in the country that scorned them or to take up the government’s offer of a one-way ticket to Japan. Either way, it was a choice that no one should ever have to make.

Tameo Kanbara is a little known hero from those days. He was one of the organizers of the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group that had the audacity to put up resistance when the evacuation order to round up and imprison all Japanese Canadians who were living within the 100-mile exclusion zone was issued. We were all not so compliant.

Their resistance, however, gave reason for authorities to put some Issei and Nisei rebel “gambariya” like Tameo, into the POW camp in Angler, Ontario, where German POWs were also imprisoned. After he was finally released in 1946, Tameo followed the exodus of JCs eastward, thousands of kilometers even further away from the BC coast into the industrial heartland of Ontario where, even there too, they were prohibited from living in cities like Toronto.

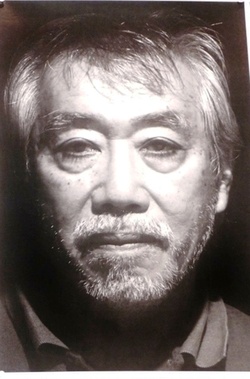

Today, Tameo’s son, Sansei Bryce Kanbara, 66, is a well respected artist, gallery owner (You Me Gallery), and active community member in Hamilton, Ontario where he was born and raised and continues to live and work. The city of about 500,000 is located 80 kilometers west of Toronto on Lake Ontario.

Can you first tell us a little about your family background? Where are they from in Japan?

The Kanbaras come from the village of Urasaki in Hiroshima-ken and Shimodas from Tsuru, Kumamoto-ken. My mother Fumiko Shimoda was born and raised in Port Moody, BC. She was the second of eight children. My father Tameo was born in Vancouver, “nisan” in a family of at least five children (there is a rumour of another sibling, a daughter, dying tragically in a gun accident). At the age of six, he was sent along with his younger brother Kenji to the family homestead for his education. He returned to Canada when he was 16 and his first language was Japanese.

As my parents entered old age, they began to reveal details about their experiences that they felt were not suitable for my ears when I was young. Their accounts of the pre-war and internment years which they had always spoken about to my sister and me, became fuller and more poignant. My mother was around 22 and managing the Holly Lodge Grocery on Davie St. in Vancouver which the family had bought just a couple of years before the war as a means to establish a financial base when she met my father at a Japanese language class he taught at the Buddhist Church. They were engaged to be married and the Shimodas were planning to build a house for them in Port Moody when the internment orders were declared.

Where were they interned?

My father and Yukio Shimoda (my mother’s “nisan”) initiated the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group resistance to the evacuation orders and were captured by the RCMP and sent to Angler POW camp (north of Lake Superior), followed by their brothers Haruo and Mits Shimoda, Kenji and Akira Kambara (sic). The rest of the Shimoda family was sent to Slocan (Bay Farm) and then to New Denver for the duration of the war.

How did they get to Hamilton?

When my uncles Haruo and Mits Shimoda were released from Angler, they eventually made their way to Hamilton as did many Japanese who headed east. Hamilton was a resting place for families while the unwelcoming attitude of Toronto subsided. The Shimoda family stayed in Hamilton and the city became home.

Where was the JC community located there?

I’m not the best person to provide an answer but I have learned through conversations that there were a number of JCs who lived either briefly, or for many years on the short streets north off of York Blvd., Grieg and Oxford for certain. And further east where York becomes Cannon St. there were rental units (on Mary and Elgin, for certain) that many JCs seemed to have passed through. A JC couple named the Dates owned a large stone building and rented to JCs such as my mother’s family when they arrived. I always wondered how they had the money to buy such a handsome building. There are stories about Mr. Date and his extramarital dalliances that surface from time to time when my mother and her siblings talk about those days. They remember the address of that stone building on the corner of Cannon and Mary which is still there and may be a heritage building.

What did your father do for work?

My father worked in International Harvester’s foundry for over thirty years. When he retired, he and my mother took a trip to Japan—the first time he had been there since he left as a teenager, and the very first time for my mother. I accompanied them on their second and final trip there in 1992 just after the last members of the family in Urasaki, two unmarried aunts, suddenly died and left the house vacant. I’ve tried to maintain the house over the years and make it available for stays by JCs and artists.

Can you describe your journey to becoming a curator and gallery owner?

I studied Art History and English Literature at McMaster University and shortly after graduation, I rented a small room above Nishizaki’s grocery store in an old downtown building on Rebecca St. in Hamilton, determined to make art work. I worked shifts at Dofasco and whenever I was not at work, I went to my room to make drawings and paintings. I was a founding member and first administrator of Hamilton Artists Inc, an artist-run centre that a small group of Hamilton artists started in the 1970s. We flew by the seat of our pants and learned how to organize exhibitions and run a gallery (The Inc, btw, is thriving today in a purchased and renovated building).

In around 1988, I became Exhibition Curator at the Burlington Cultural Centre, and later worked at the Ontario Arts Council, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. These job stints left me disillusioned about the public art system. I bought the small storefront building on James St. North on a block of mostly vacant buildings and opened You Me gallery in 2003. Ensuing arrival of other galleries has established the street as an art district and spurred the dramatic revival of a beleaguered north-end neighbourhood.

Life Support installation, 500 sheets of drywall, McMaster University, Nuclear Reactor precinct (2004)

How much was being Japanese Canadian part of this? I remember you had a show called something like “About Nikkeiness”. Any insights from that show that you can share?

When I look back, I can see a long JC thread that goes back to early ethnic-identity works I made just after university—they’re images that appeared unexpectedly, mostly solitary, “kimonoed”, Asian-looking people which others have described as self-portraits. I was really interested in how other JCs, and particularly JC artists, addressed their ethnicity and this lead to my involvement in the Hamilton JCCA and over the course of many years, to various roles at the provincial and national levels of JC organizations.

In the 1990s I was Executive Director of the Toronto Chapter NAJC for a couple of years which gave me the opportunity to combine JC and art interests. We organized the Ai Symposium in 1994, the first national get-together of JCs in the arts, and revived the Shadow Project at Toronto City Hall to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the end of WW2. I met Toronto JC artists Kazuo Nakamura, Heather Yamada, David Fujino, Louise Noguchi, and Akira Yoshikawa when I was part of the Centennial Art Exhibition Committee in 1978 and have coordinated/curated a string of JC exhibitions and projects since then: Shikata ga nai, Japanning, and many shows at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre where I’ve been doing curatorial work for a while now.

Can you describe the art scene in Hamilton?

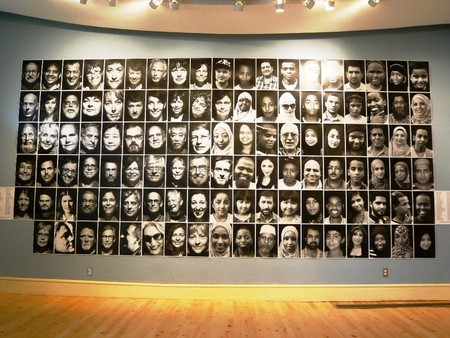

I have lived in Hamilton all my life. Lately, I’ve been working with photographers (I’m not a photographer) on projects that attempt to create interaction among Hamilton’s diverse (and insular) communities. We’ve done photo exhibitions of families at dinnertime, residents in neighbourhoods affected by steel plant emissions, and right now, we’re exploring ways to collaborate in a similar way with urban Aboriginals. I’m on boards of organizations with mandates and programs to challenge racism and promote inclusion, but it seems to me that change happens when people begin to interact with one another at a personal level. In the past decade the exploding art scene in Hamilton has drawn national attention. There are strong forces pulling it in all directions, and it’s both exciting and perplexing to watch the changes. The influx of artists from Toronto and further afield makes for interesting artistic and social chemistry.

Taking a look at the Canadian art scene, can you tell us about some Nikkei artists who have had an impact on it?

The Nisei triumvirate of artists is Roy Kiyooka, Kaz Nakamura, and Tak Tanabe. They were born in the same year, 1928. Nobuo Kubota was born later, as were Shizuye Takashima and Walter Sunahara and Aiko Suzuki. All are gone except Tanabe, and each of them was an against-the-grain model of individuality and creativity. Every JC should know about them and their work.

Any up and coming Nikkei artists who we should keep an eye out for?

If your eyes are open, you’ll see them. In general, Nikkei are slow to recognize and appreciate the artists among them.

Is there anything uniquely Japanese Canadian about their art that you can put a finger on?

I think if you are JC, JC art should make you self-conscious in one way or another. It makes you reflect on being who you are, why you are doing what you do.

Do you have a personal motto?

Turning Japanese is easier said than done.

From an art point of view, what aspects of our identity need to be explored?

I’ve always felt there’s an untapped Japanese Canadian aesthetic that comes from the Issei and Nisei—the way they fashioned their surroundings by improvising shelters, gardens, household implements, and amenities with materials at hand. Using scrap lumber, my grandfather built house additions, ofuro, and rowboats so the family could fish and row across Burrard Inlet (in British Columbia). I don’t know where he learned to do those things. My father once made a lawn rake from wire coat hangers. I’ve seen photos of JCs in theatrical and musical events in the camps; they practiced odori and ikebana and haiku as routine activities. Many of these things were JC adaptations of refined Japanese traditional craft and lore. There’s something unadorned, familiar, and appealing about them—a JC kind of “wabi-sabi”.

* Learn more about the You Me Gallery at http://www.youmegallery.ca/

© 2014 Norm Ibuki