Identifying the Copier

If we were to imagine the copier and burier of the Lotus Sutra Stone Scripture based on the results of the examination described earlier, the person would be a detainee, conversant with the Lotus Sutra, skillful in coping and burying Buddhist scriptures, and an able calligrapher (it is actually quite artful work).

A single likely candidate emerged from a search of articles appearing in the Heart Mountain Sentinel: the Rev. Nichikan Murakita, a detained missionary in the Nichiren lineage (more precisely, a Honmon School of Hokkeshu). A leader of the Heart Mountain Buddhist Association and of the detainee community generally, he was one of the calligraphy teachers in the concentration camp whose lectures on the Lotus Sutra were mentioned frequently in the camp’s newspaper.

A brief biography of the Rev. Murakita, based on research materials from both Japanese and U.S. sources, is as follows:

Yoshitaro Nichikan Murakita, a monk of Hokkeshu (Honmonha); born January 10, 1907 (Meiji 40) in Sakaida City, Kagawa Prefecture, his father a manager of a farm garden; ordained by the Rev. Nikkyo Kenshouin at Honmyoji Temple in Udazumachi; entered the sect’s school in March 1926 (Taisho 15) and taught by the Rev. Nichiji Fukuhara in Hongakuji Temple, Osaka.

After graduation in March 1929 (Showa 4) entered Toyo University (Oriental Literature, Ethics Department, Special Course), Division 2, graduating in March 1932 (Showa 7); stationed in San Francisco as a special missionary teacher in the United States in September 1933 (Showa 8) and later entered the University of California, Los Angeles (Graduate School?), receiving, according to detainee-provided information recorded in the camp’s official registry, the degree of Master of Arts.

Leaving the university upon the outbreak of the Pacific War; competent in both Japanese and English and good in calligraphy; built California Mountain, Nichirenji Temple, becoming abbot of it in Los Angeles in 1940 (Showa 15); worked for Hollywood Japanese School (Seirin Nihongo Gakuen), a middle school; retired from it upon leaving the U.S. in 1943 (Showa 18).

Detained upon the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941 (Showa 16) at the Santa Anita Assembly Center and sent to the Heart Mountain concentration camp on September 3, 1942; active as a Nichiren sect missionary, one of the leaders of the Heart Mountain Buddhist Society, a calligraphy teacher, and a member of Kagawa Prefectural Association.

About a year after concentration encampment, left to return to Japan with his wife Masako on August 24, 1943; returned to Japan by the ship Teia-maru, a diplomats’ exchange ship; conscripted in Japan, but later released; lived in Hongyo-in, Tacchu (a supporting branch) of Honnoji Temple, Kyoto; became abbot of Honmyoji Temple, Udazu, Kagawa Prefecture.

Passed away at the age of 76 on June 10, 1983 (Showa 56), his last rank being Deputy Archbishop (Gon-Dai Sojo).

It cannot be clearly determined whether this instance of copying (a part of) the Lotus Sutra and burying it in the concentration camp’s cemetery was carried out by the Rev. Murakita alone, or in cooperation with fellow detainees. Given his leading position in the camp, it is conceivable that he received assistance from Nichiren sect followers, calligraphy students, or volunteers of the Kagawa Prefectural Association. If so, the rather laborious work of collecting the stones (examination of photographs and maps suggests they were collected from the banks of the nearby Shoshone River, where they would have been polished smooth by the force and pressure of the water), producing the Stone Scripture, transporting it from copying place to cemetery, and burying it in a metal drum underground could be carried out comparatively smoothly. It is not, however, impossible that the work was carried out by a single individual by use of skillful means.

Because subsequent research has revealed that the Rev. Murakita was the only Nichiren sect monk detained in the Heart Mountain concentration camp, it seems certain that no other teacher of the same sect copied the Lotus Sutra Stone Scripture now belonging to the Japanese American National Museum. It appears that he was unable to complete all volumes of the work due to his having been released from the concentration camp after about a year of detainment.

The fact that his copying practice seems never to have been reported in the camp’s newspaper suggests that the work was carried out by the Rev. Murakita as a completely private aspiration and action, without any publicity. He did not seem to talk about his concentration camp activities, including this copying practice, even after his return to Japan. Until now no record or report of this activity has been found.

Cultural Tradition of Scripture Copying and Modern Examples

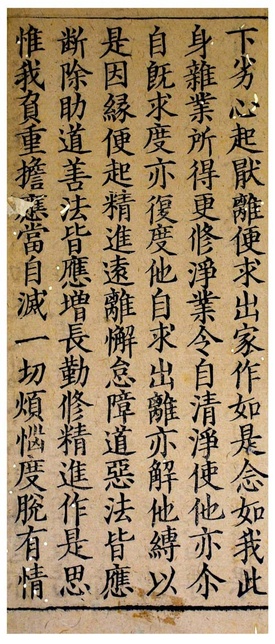

[inline:Chinese_printed_sutra_sm.jpg]

While not directly related to the Stone Scripture under consideration, a brief discussion of the Buddhist cultural tradition of scripture copying and burial will put the Rev. Murakita’s moving effort into context.

In ancient India, Buddhist scriptures were transmitted orally from master to disciple, generation by generation. Eventually the practice of copying scriptures developed, and one finds, especially among Mahayana texts, mention of the merit produced by copying scriptures such as the Lotus Sutra. The dissemination of Chinese translations based on the original Indian texts is thought to have been facilitated by the invention and wide availability of paper in China beginning in the second century, C.E.

The Chinese language scriptures by which Buddhist teachings were transmitted to Japan from China to Korea from the middle of the 6th century were all “copied scriptures” (sha-kyo). The Japanese government set up an official scriptorium in Nara, the 8th-century capital, for the extensive copying and wide dissemination of these Buddhist texts. Gradually, in addition to studying and understanding the contents of the scriptures, the act of copying itself came to be considered an important Buddhist practice producing great merit. The practice was adopted by devout renunciants and lay people alike, spreading throughout Japan with a variety of texts, objectives, and distinctive forms such as the ritual burying of the copied texts.

In the Heian Period, for example, the construction of burial mounds to preserve sealed copies of important scriptures became popular. With the contemporary awareness of “the coming of the Degenerate Era” and the faith in Maitreya Buddha as the coming future Buddha, the practice of burying scriptures was undertaken to preserve the texts until the time of Maitreya’s descent some “5,670,000,000” years later. This time capsule concept is termed a “Scriptural Mound of Buried Scripture.”

Variations of the activity continued from the Kamakura Period (c. 1185-1333) to the Muromachi Period (c. 1336-1573) as people known as the “Sixty-Six Saints” traveled throughout Japan’s 66 provinces, encasing scriptures within shrines and temples or burying them in scriptural mounds. This “going around counties and enshrining scriptures” was widely practiced, and “Scriptural Mounds of Enshrined Scriptures” can be found in many places now.

In the Azuchi-Momoyama (c. 1573-1603) and Edo Periods (c. 1603-1868), copying scriptures onto small stones (rekiseki) and burying them together underground became quite fashionable. Accessible to people with limited financial means, this practice was undertaken in many places, with many remains extant, and may be considered an expression of the popularization of Buddhist belief.

Even today, the hand-copying by brush of Buddhist scriptures in temples is alive and flourishing all over Japan. Among Pure Land followers, parts of the Pure Land Scriptures such as the Amidakyo are frequently copied. Parts of the Lotus Sutra or, because of its shortness and superb content, the Heart Sutra, are popular among Nichiren, Tendai, and Zen practitioners. In this way, the ancient cultural tradition of copying scriptures continues to this day.

I would like to present here three additional unique and valuable instances, undertaken in modern times, that will recollect the Buddhist nexus with the scriptural copying of the Rev. Murakita.

The first instance is a tower titled “One Character per Stone Lotus Sutra Tower,” located in Seattle on the U.S. west coast. It was built in prewar 1931 by members of the Japanese Nichiren sect on the burial spot of a stone scripture featuring a portion of the Lotus Sutra. This site, probably known to the Rev. Murakita and seeming to have had some influence on him, is thought to be the first instance not only in the United States, but anywhere outside of Japan, of the construction by Japanese people of a tower marking a buried Lotus Sutra stone scripture.

The second instance is a scriptural mound built on a place named Kyo-ga-dake (Scripture Hill), located between the 5th and 6th stations of Mt. Fuji. This is said to be the site where Nichiren Shonin, the founder of Nichiren sect, enshrined the Lotus Sutra, praying for the protection of the nation. Because the site had become quite desolate, the Tokyo Betsuin (Annex) of Minobusan, the head temple of the Nichiren sect, newly built the scriptural mound there.

Volunteers from the Tokyo Betsuin congregation copied important portions of the Lotus Sutra, one character per stone, put the stones into small bags, and carried them to the Kyo-ga-dake to be enshrined underground. At present, this site of the outer precinct of Minobusan consists of the hall enshrining the congregation’s statue of worship, a standing bronze figure of Nichiren Shonin, and the newly built spititual mound, its stone room containing the Lotus Sutra in Sanskrit in 12 fascicles in addition to the new stone scripture. (Materials supplied by the Rev. Kyoukou Fujii, Prof., Univ. of Hokkaido, abbot of Tokyo Betsuin, Minobusan, noted with gratitude).

The third instance is the “O-daimoku Tower” built by the Beikoku Betsuin (U.S. Annex) of the Nichiren sect in Los Angeles (Rev. Shokai Kanai, then abbot) in April 2003, in commemoration of the 750th anniversary of the founding of the sect (2002). Included at this site are tanzakus (long strips of paper) on which are written the o-damoku “Nanmyohorengekyo” (mantra of “Devotion to the Lotus Sutra”) and a major portion of the Lotus Sutra itself in Japanese and English. The copiers included Japanese people, Japanese Americans, and many Americans. The Betsuin newsletters, a list of the Betsuin membership, and a record of the copiers were buried together with the texts. (Materials supplied by the Rev. Shokai Kanai noted with gratitude.)

In Conclusion

This is the 65th year after the conclusion of the Pacific War, during which Japan has enjoyed economic prosperity and peaceful living. A few of the young are said not even to know of the war between Japan and the U.S. However, observances of atomic bomb suffering in Hiroshima and Nagasaki every year in August remind us of the miseries caused by the war and of our vow for peace.

As noted earlier, a chance encounter introduced me to the Stone Scripture housed in the Japanese American National Museum, and I undertook the solving of its enigma. In this process I was given a glimpse of the suffering of Japanese immigrants since 1868 (Meiji 1), including racial discrimination and especially their unreasonable detainment in U.S. concentration camps.

Today the living realities of Japanese Americans during wartime are almost unknown in Japan. However, I consider this detained living, though not a deprivation of life, to be “the Third Passion”—paralleling the suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to be long remembered and told continuously.

The history of the introduction and dissemination of Japanese Buddhist sects in the United States begins in the middle of the Meiji Era (end of the 19th century) and is halted at the outbreak of the war. The next chapter begins with the Japanese Americans’ liberation and return home after four years’ detainment, the restoration of their temples, and the resuming of cultural and religious activities.

But the period of hard detained living in concentration camps during the war is completely missing from this history. The Buddhist activities of 120,000 Japanese Americans among the ten U.S. concentration camps must have developed uniquely in each place, as observed in the Heart Mountain concentration camp. Researching and recording the realities of this blank period and enlightening Japanese and American people will be one of the important future tasks for specialists in the history of overseas propagation of Buddhist sects and of the problems faced by Japanese immigrants in the United States.

For now, I publish this paper desiring that as many people as possible learn about this instance of the Heart Mountain concentration camp, a part of which I have been able to clarify. I hope the facts and background presented here will be correctly presented and explained when the Lotus Sutra Stone Scripture is exhibited at the Japanese American National Museum or other U.S. institutions in the future, and I expect knowledge and understanding about this subject to spread wider as a result.

* Dr. Mori wishes to acknowledge and express his appreciation of the special cooperation of Ms. Nancy Araki, volunteer Mr. Henry Yasuda of the Japanese American National Museum; Mrs. Toshiko McCallum, then reference librarian; Ms. Susan Fukushima, then reference librarian of the Hirasaki Resource National Center in the same museum, et al., in this research and study.

*This article was originally published in the Interreligious Insight, Vol. 9, Number 1, July 2011.

© 2011 World Congress of Faiths, Common Ground, and Interreligious Engagement Project