“If California has made any contribution to sport on a national level, it is in the democratization of pursuits that were previously the prerogatives of elites,” noted the dean of California history Kevin Starr in 2005. “Most of the champions of the twentieth century who come from California first developed their skills in publicly subsidized circumstances: municipally supported swimming pools, golf courses, and tennis courts in particular, where middle class Californians, thanks to the recreational policies of Progressivism, were introduced to these previously social register sports.”1

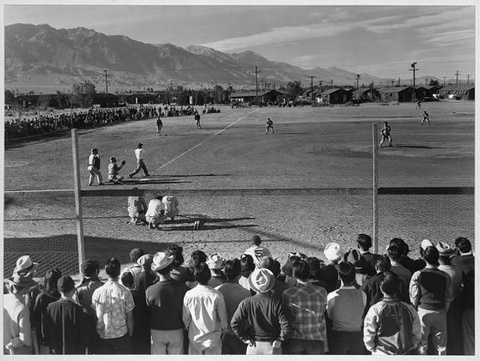

Baseball game at Manzanar War Relocation Center | Photo: Ansel Adams, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Indeed, even under the weight of racism, groups denied equal access to mainstream U.S. society found sports as a means to greatness and, in part, as a declaration of their commitment to America. Take two-time gold medalist Highland Park native Sammy Lee, or Hall of Fame baseball player and former South Pasadena resident Jackie Robinson, both of whom labored under the auspices of segregation and racism to assert their own, and by extension their fellow Korean and African Americans’, claim to equality. Indeed, Southern California has proven a vital region for promoting the interests of racial and ethnic equality through athletics.

Undoubtedly, figures such as Lee and Robinson remain critical to postwar civil rights battles, yet more ordinary but nonetheless important examples have often gone ignored. For Japanese Americans, Southern California and baseball, though never producing a luminous icon on par with Lee or Robinson, served as critical factors shaping Japanese American identity, binding ethnic enclaves across the West Coast, forging ties with Japanese culture, and promoting civil rights. Moreover, in the face of debilitating internment policies, baseball provided a way to mitigate the trauma of forced incarceration.

However, before one delves into baseball’s meaning for Japanese Americans and Southern California, Japan’s embrace of the sport needs to be discussed. In the late 1800s, the Japanese government engaged in a process of industrialization and modernization commonly referred to as The Meiji Restoration. Promoting a new industrialized economy and hoping to stake a claim internationally as a global power, Japanese officials established a constitution, created a legislative diet, and urbanized. Turning away from the more isolationist nature of the Tokugawa period, officials sought to simultaneously assert Japanese culture while advocating a set of ideals based on patriotism, industrial productivity, modernization, and teamwork. Baseball fit neatly into this dynamic.

With the combined efforts of American Horace Wilson and Meiji official Hiroshi Hiraoka, baseball flourished across Japan. In 1871, Hiroshi established the Shimbashi Athletic Club, the first of its kind in the nation, and soon the sport expanded in the Japanese imagination. Americans too saw in baseball the symbol of national ideal and by the 1880s, the sport became widely viewed as “the ‘watchword of democracy’,” notes historian Samuel A. Regalado in his compelling 2013 work, Nikkei Baseball: Japanese American Baseball from Immigration to Internment to the Major Leagues.2

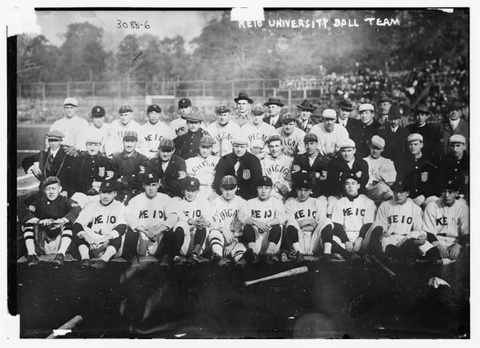

Keio University baseball team in Tokyo, with visiting players from Chicago White Sox and New York Giants, 1914 | Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Americans like Wilson wanted to export baseball as a means of spreading democracy and opening markets, while simultaneously promoting individualism and teamwork. With that said, such attitudes came with more than a touch of colonialism. Baseball, argued historian Edward M. Burns, “would fire the imaginations of foreign people and stir their countries from sluggishness and from enslavement to outworn habits and institutions.”3 In the Philippines, American officials oversaw the development of a physical education program meant in part to instill American values and “discipline,” through sport. Baseball occupied a central place in this configuration. Colonial governors sponsored nationwide baseball tournaments, and by the 1920s more than 1,500 schools fielded teams across the archipelago. Ultimately, basketball would win the hearts of Filipinos, but from 1910 to 1930, the U.S. heavily promoted its national pastime among its colonial subjects.4

Whatever the colonial associations, Japan saw similar promise in baseball, believing the sport to be an important part of exerting Japan’s new international image. Meiji leaders supported the sport’s ability to reshape the image of Japan while also facilitating international connections. As industrialism and Japan’s standing expanded between 1880 and 1910, so too did baseball’s popularity among the nation’s citizens.

Undoing tropes assigned to Asian nations and their peoples has long been a struggle. In the 1970s, the late great Edward Said documented the West’s tendency to portray Eastern nations as feminine, sensual, and erotic, which within the context of gender relations of the nineteenth and twentieth century assigned Asia and its residents to a secondary status, in comparison to the rational, masculine, and scientific West. Known as Orientalism, this theoretical formation facilitated European imperialism and created an uneven dichotomy for Japanese leaders and its people. Baseball, its inherent masculinity, pushed back against such negative idealizations, or to paraphrase Harvard historian Akira Iriye, Japan went from sensual exoticism to masculine competitiveness.5

Unfortunately, for many Japanese farmers, modernization efforts resulted in the loss of whatever lands they had for cultivation, as industrialization resulted in higher property taxes that pushed 300,000 farmers from the fields. From 1885 to 1907, 155,000 Japanese traveled East to Hawaii and the American West Coast. Hawaii provided the first stop for many of these migrants, with nearly 25,000 settling there by 1896. Unsurprisingly, Japanese baseball leagues first emerged in the U.S. territory and often featured multi-ethnic/racial competition, as caucasian, Filipino, Portuguese, and Japanese laborers exhibited their skills on the diamond. As more Japanese immigrated to California, Washington, and Oregon, the leagues followed. By 1900, over 24,000 resided in mainland America, with just over 10,000 in California alone. San Francisco fielded the first U.S. mainland team comprised of Japanese American players in 1903, with the creation of the Fuji Athletic Club.6

As baseball grew in popularity in California throughout the nineteenth century, the California League was developed in the 1880s, which eventually morphed into the Pacific Coast League (PCL) in 1903. “For more than half a century,” points out Starr, this league proved an “extraordinary popular and successful venture in terms of the number of cities represented, of successful stadiums, and of notable players,” among them Joe DiMaggio of the San Francisco Seals, and Ted Williams of the San Diego Padres.7 Banned by segregation, Japanese American leagues developed alongside the PCL, and though they produced few, if any, players of the stature of Williams or DiMaggio, they nonetheless sutured the community’s urban-rural diaspora across the state and the West Coast.

While the first clubs formed in Northern California, by the 1920s and 1930s the best team, the San Fernando Nippons (later the Aces), could be found in Los Angeles. Likewise, by the mid-1930s worthy competitors such as the San Pedro Skippers emerged from Japanese American enclaves around Los Angeles. Southern California’s weather enabled year-round play, which helped to give coherence to the Japanese American community across the “vast” expanse of Los Angeles.8 In this way, these baseball clubs cultivated Japanese American civil society in an era of “yellow peril” and anti-Japanese legislation, which ranged from discriminatory state laws prohibiting Asians and newcomers from land ownership, to immigration legislation like the 1924 Johnson and Reed Act, which more or less banned citizenship for Asian immigrants.

Clubs soon emerged in Fresno, San Jose, Stockton, and elsewhere, including Portland, Seattle, and their hinterlands. Japanese American presses, like San Francisco’s Nichi Bei Shimbun (1899) and L.A.’s Rafu Shimpo (1903), played critical roles in baseball’s popularity, while contributing mightily to the kind of civil society so important to American immigrant groups by providing first generation Japanese, commonly referred to as Issei, with information on local enclaves and news from Japan.

Notes:

1. Kevin Starr, California: A History, (New York: Modern Library, 2005), pg. 299.

2. Samuel A. Regalado, Nikkei Baseball: Japanese American Baseball from Immigration to Internment to the Major Leagues, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013).

3. Ibid.

4. Rafe Bartholomew, Pacific Rims: Beermen, Ballin in Flip-Flops and the Phillipines’ Unlikely Love Affair with Basketball, (New York: New American Library, 2010)

5. Samuel A. Regalado, Nikkei Baseball, 2013.

6. Ibid.

7. Kevin Starr, California: A History, pgs. 300-301.

8. Ibid.

*This article was originally published on KCET Departures’ website on January 10, 2014.

© 2014 KCET; Ryan Reft