Haiku that crossed the ocean with immigrants

When Professor Hosokawa Shuhei (International Research Center for Japanese Studies), who won the Yomiuri Literature Prize in 2009 for his book Tooku arite tsukuroku (What We Make in the Distance) (Misuzu Shobo), an interpretation of Brazilian immigrant literature, gave a lecture here, he said, "I hear that Western newspapers do not generally have literary pages that publish works submitted by citizens. But literary sections exist in Japanese newspapers, and even in Japanese-language newspapers overseas. This shows the cultural level of the Japanese people." I was impressed.

The book uses "nostalgia" as a keyword to provide an overview of immigrant literature. For example, in the phrase "Buried one meter away from Japan," the author explains the unique feelings of immigrants that arise during the funeral of a relative: "One meter of closeness is no comfort to either the living or the dead. The humor and sadness of this phrase lie in the fact that the poet makes the effort to state this."

* * * * *

"I came here thinking it would be my last time," said Eliza Kobayashi (93), a second-generation Japanese woman, as she arrived at the reception desk accompanied by her two daughters at 9 a.m. on October 19.

This was the scene just before the start of the 36th Nenpuku Ki, 26th Kiyoko Ki, and 4th Ushidoji Ki All-Brazil Haiku Competition (hosted by the Sao Paulo Mokage Haiku Association and supported by Asahi Publishing Co.) held at the Junior High Association Hall in the Liberdade district of Sao Paulo. Portraits of the three deceased were lined up on the altar, and tropical fruits, whiskey, and dekopon were also offered in the beautiful light of many yellow chrysanthemums.

A total of 47 people, including Elisa's direct disciples, disciples of Elisa, and even modern haiku poets, came from over 1,000 kilometers away, including Nabirai and Dois Irmãos in Mato Grosso do Sul, Rio City, and the interior of the Sao Paulo region, to participate in the event and spend a day immersed in haiku while remembering the deceased. 23 haiku were submitted from the Japanese haiku magazine "Kunenbo," and four of them were selected as special winners.

In the early days, only some cultural figures

The first Japanese-language newspaper in South America, the weekly Nanbei (South America), first published in January 1916, already had a haiku column, written by publisher Hoshina Kenichiro, who had relocated from Hawaii. Haiku also began along with the history of immigration. The following two haiku poems, written by Uetsuka Shuhei (pen name Hyokotsu), the "father of immigration" who looked after the immigrants on the first immigrant ship, the Kasato Maru, out of concern for the situation of people deserting from farmland, are extremely famous in the area.

"As evening falls, I cry in the shade of the trees and pick coffee" (Hyokotsu)

"I think of the immigrants who escaped at night, the withered field stars" (Hyokotsu)

The prewar agricultural magazine Nougyou no Tomo (Friends of Agriculture) appointed Suzuki Nanju as the editor, and the activity of writing poems about flowers, birds, the wind, and the moon in Brazil was naturally woven into all Japanese media. First, haiku societies were organized around prominent haiku poets, which then became the basis for the establishment of haiku circles in newspapers and magazines, and from there the launch of haiku magazines.

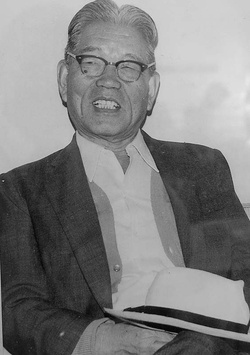

At first, haiku was mainly written by intellectuals, but thanks to the efforts of Sato Nenpaku (1898-1979, real name Kenjiro, Niigata) and others, it gradually spread to ordinary immigrants. He was selected for the Hototogisu contest for the first time in 1921 (Taisho 10), and was a talented student of Takahama Kyoshi, the "genius of the Hokuriku region," and was expected to have a bright future.

He received a parting poem from Kyoshi saying, "Work in the fields and develop the country of haiku," and in 1927 (Showa 2), he traveled to Brazil and settled in the Second Aliança Colony in the interior of the state of São Paulo. He dedicated his life to spreading descriptive haiku to the Japanese community.

The Alianza settlement, which is celebrating its 90th anniversary this year, is known for being the place where many intellectuals who were influenced by the wave of Taisho democracy settled. At the time, the area was also called the "Ginza Strolling Immigrants" because intellectuals who would hang around Ginza at the time would set out to reclaim virgin forests with their belongings such as pianos and gramophones.

The literary magazine "Okabo" started in the Alianza settlement

"Thunder, child of the sea of trees on all four sides" (Nenbura)

"The foreigners I employed are immigrants, and the autumn is full of cotton" (Nenpaku)

Other poets who settled in Alianza in 1926 included Kimura Keiseki, also of the Hototogisu school, and Iwanami Kikuji, a poet of the Araragi school who looked up to Shimaki Akahiko as his teacher and the local "father of tanka."

In July 1929, the Japanese-language newspaper "Nippo Shimbun" established a Japanese-Brazil haiku column called "Okabo," with Keiseki as a selector. Until then, there had only been haiku meetings and individual publications, but this was the first newspaper haiku column in which the works were selected by a judge, and it gained a great deal of momentum.

With Keiseki and Iwanami at the core and support from Nenpuku, Brazil's first literary magazine, Okabo (a joint magazine of haiku and tanka), was launched in January 1931. At first it was printed by mimeograph but then switched to movable type and publication ceased after the 12th issue, but it produced many successful writers after the war.

Around 1936, the term "Brazilian seasonal theme" began to be used, and a focus on a style that emphasized the uniqueness of the region was born, and the "Flower and Bird Research Society" was organized in the city of São Paulo, with Gyosetsu as its leader.

Sansui-kai welcomed Kimura Keiseki, who had come to São Paulo from the interior of Aliança, and in 1937 (Showa 12) published the haiku magazine Southern Cross with him as publisher and editor. However, Keiseki passed away and the magazine ceased publication after the third issue. Brazil's first collection of haiku, Keiseki Kuushuu (Collection of Kimura Keiseki's Posthumous Manuscripts), was published in 1939.

Until before the war, the focus was on cultural figures who had learned to compose haiku in Japan.

© 2014 Masayuki Fukasawa