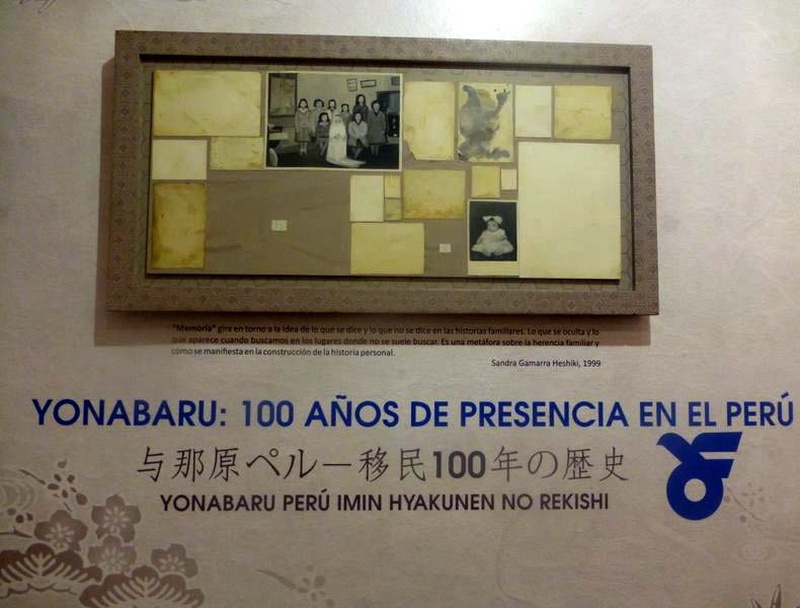

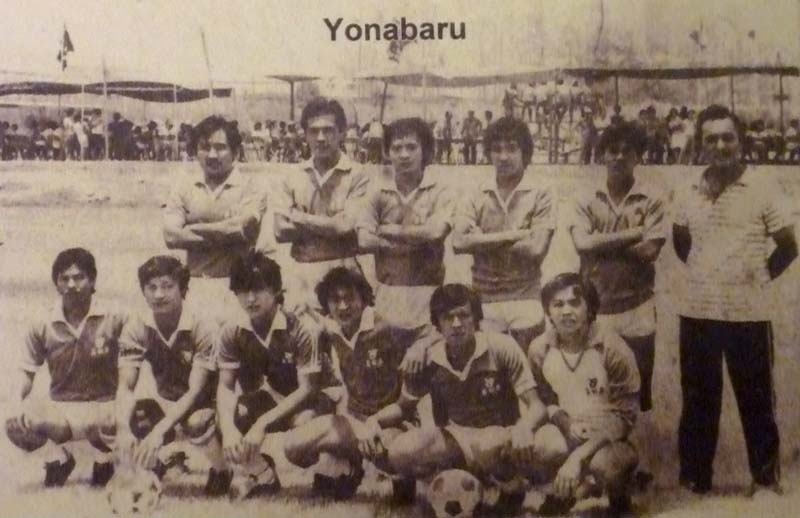

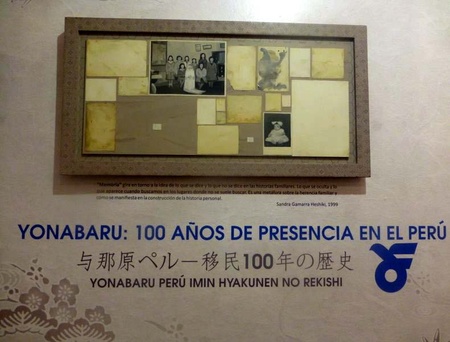

“Yonabaru: 100 Years of Presence in Peru” is the title of the exhibition that opened last Wednesday, September 12 at the facilities of the Peruvian-Japanese Association in Lima. It is an exhibition that tries to tell us the history of the Yonabarunchu community in Peru, since this year commemorates the 100 years of the arrival of the first group of Yonabarunchu to Peru. But, it is not a boring exhibition about history, it is a dynamic exhibition told through the photographs and objects that are on display.

The first time I saw the exhibit, I felt like I was walking through a time warp. The photos and objects were arranged chronologically and when I saw them I could recreate and imagine, for example, the moment when my grandparents arrived in Peru or when they opened their first cafe or they made me remember what my mother told me about her school days. , where I had to take the tram to get to Hoshi Gakuen, which was a Japanese school in Lima where many Issei children from Yonabaru studied. Anyway, there are so many memories that came to mind on the day of the inauguration.

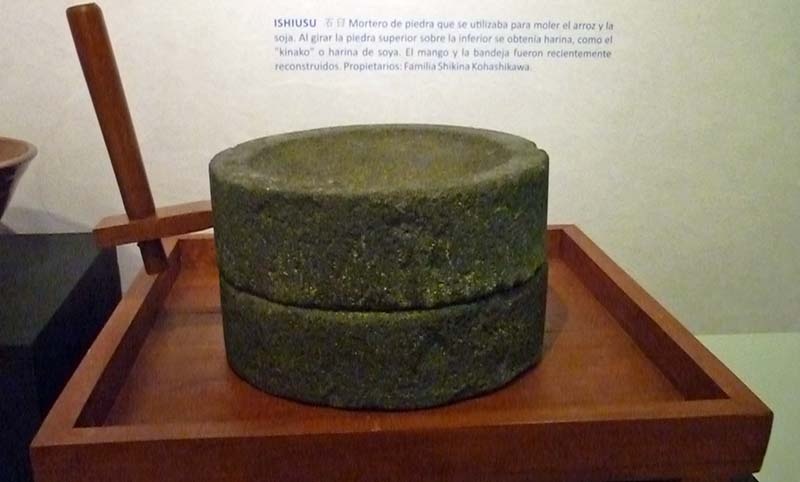

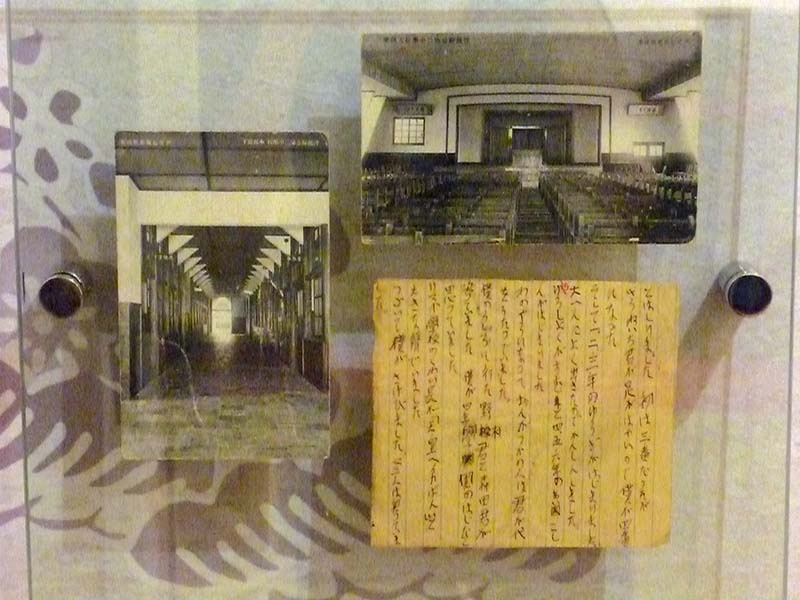

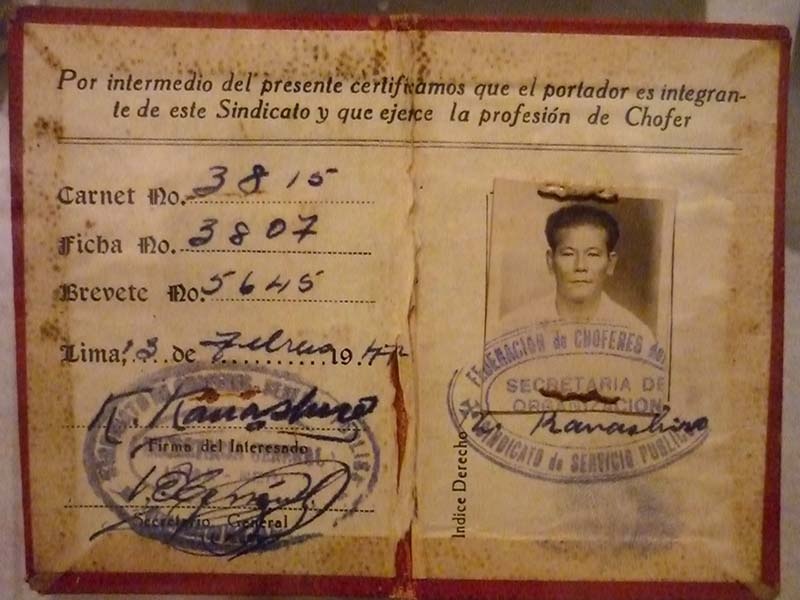

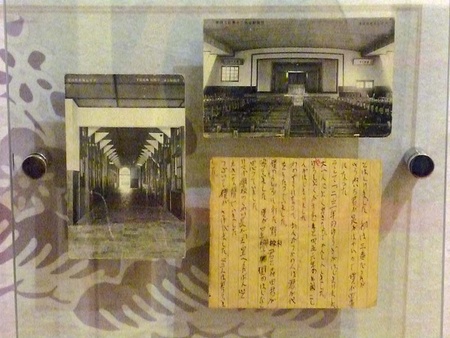

For several months, the organizers of the exhibition held a call among the members of the chojinkai and asked us for old photos of our grandparents or the things they had used (clothes, documents, objects in general) and many, like me, asked. We started looking through the old family albums and dusting off the things that were already almost forgotten in some corner of the house. We gave them our best family treasures, which were photos, old documents such as koseki , old passports, work contracts, objects brought with them from Yonabaru, such as suribachi , ishiusu , koto , the clothes they wore. Anyway, the list is quite long but I think many of us felt proud of the things we kept at home and said: “Look, this is what my son used” or “This photo was taken more than 60 years ago.” . The organizers had the difficult task of selecting the most suitable objects or photos for this exhibition.

While looking for photos or things of my oba for the exhibition, I felt like I was reconnecting with the past. I found old photos, in black and white, where my oba or my oji appeared, but accompanied by many people that I did not know, but whose faces were repeated in one and another photo or documents that I did not know were stored in my house. It seemed as if I were putting together a puzzle, where each photo or document was like a piece of a whole puzzle that was our grandparents' past. My mother no longer remembers many things that my oba told her and I, at that time, was too young to retain everything I heard from my oba . As for this exhibition I was lucky enough to collaborate not only by lending photos or old things, but also by searching for information about the history of the yonabarunchu , I took the opportunity to reconstruct that past and give meaning to all those scattered memories that I have of my oba .

Although she told us little about Yonabaru, I remember that she always said that there were farms and that my oji used to climb trees when he was a child. And with all that, I imagined it as a small country town, which had nothing interesting about it. And now that I remember it, my oba always talked about the farm and the sweet potatoes. Here in Peru, she liked to eat parboiled sweet potatoes, even more so if they were purple ones, because she said that was what was eaten the most in Yonabaru and Okinawa. And I also remember that my mother told me a rather romantic story about my grandparents' arrival in Peru, saying that it was to spend their honeymoon here, although the first thing they did when they arrived in Peru was work on the Paramonga ranch.

I searched in books and the internet and asked acquaintances, thus finding information about Yonabaru and I realized that my grandparents' town was more than a farm and many trees. I did not know, for example, that Yonabaru was known for its traditional 400-year-old Tsunahiki festival or that Yonabaru was one of the stations through which the Naha-Yonabaru railway passed when Okinawa still had a railway system that linked to almost the entire island before it was destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa. Or that Yonabaru is known for manufacturing red tiles or Akagawara or that it is the town of the “ Basha sunchaa ”, as the people who ran the horse-drawn carts were called in the pre-war era.

Well, I didn't think that my grandparents' town would have had so many attractions, I thought it was a town very far from the capital and almost forgotten, or as my mother said, "a very inaka town."

I shared some of that data with the organizers and, together, we reconstructed that story of Yonabaru, the one that our grandparents have surely told us since we were little, but that we often forget over time and that generally we do not find it in books, but in oral tradition.

In my house we have many old photos, mostly of my grandparents, and I think we have kept them until now only by chance. We had them stored in family albums tucked inside boxes that almost always remained closed and that's how we forgot about them. Actually, this was a scene that was repeated in other families.

If it weren't for this exhibit, I'm sure I wouldn't go through those photos again. After years I opened those old albums again and began to look and select the best photos I had of my oba. When I delivered the photos to the organizers, many of them taken at the chojinkai meetings in Lima, I was surprised that other people had the same photos and where their oji or oba appeared. For me it was a somewhat curious situation because in a group photo my oba could appear and also the oba of another person whom I had barely met that same day. It was as if history were repeating itself, where our oba had met many years ago and now it was us, their grandchildren, who met many decades later. Or the time a lady recognized her grandfather in a photo I had and it turned out that he was a distant cousin of my friend . And the funny thing was that this was the first time I had seen that lady! But really, all this should not surprise me, if I have always heard my oba say that all Uchinanchu people are like a big family. This was probably why she said it.

With all the material ready, the organizers set up the entire exhibition as a time tunnel, where we would imaginarily travel through time through the photos and objects. At the opening of this exhibition, many people reunited with their friends, acquaintances and family and even their old schoolmates. Really, it was a night of reunions with the people and history of our grandparents.

But what seemed most significant to me about this exhibition is what lies behind it, which was the collaboration of several people outside the chojinkai , lending objects, documents and even correcting data that oneself did not know, all so that this exhibition, organized by Yonabaru Chojinkai of Peru, be a success. I have met some people who did not hesitate to help me when I asked them if they knew anyone or knew about something and even their willingness to lend objects they had in their homes for this exhibition without wishing they had met me before in person, only through social networks! . But they told me: “I would be happy to collaborate.” People like Rubén with grandparents from “ Naichi ” or like Ángel, who was also from another “ sonjin ” or like Nora, an Okinawan Argentine who showed that distance is no impediment. In short, I believe that this feeling of cooperation and trust is part of the icharibaa choode that is talked about so much and that characterizes the Okinawans and their descendants.

I really learned a lot from this exhibition, which allowed me to learn a little more about my grandparents' town and allowed me to reconnect with my origins and feel proud of it, while still recognizing all the hard work and sacrifices that our grandparents went through in Peru, making all that effort worthwhile and now we honor them in this exhibition.

* Yonabarunchu = person born in Yonabaru (southern Okinawa)

** All photos have been originally published on the Facebook of the Okinawan Association of Peru and are property of Rubén Kanagusuku (Peruvian Nikkei journalist from the newspaper Peru Shimpo), who kindly allowed me to share them for this article. You can view the rest of the photos the photos in this link:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Asociaci%C3%B3n-Okinawense-del-Per%C3%BA/269515980318

© 2014 Milaguros Tsukayama Shinzato