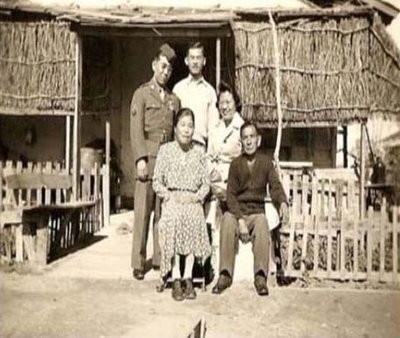

The story of my middle name brought pride and also pressure to me at a young age. My middle name is Chiyoko, named after my grandmother Chiyoko, my father’s mother. My grandmother suffered from stomach cancer before I was born. She tried to stay alive to see me born but passed away a few months before my birth. My parents described to me how sad the family was with the death of my grandmother but I brought happiness back to the family. My parents’ favorite memories of me as a baby were taking me to my grandpa’s house where he would sing and dance with me.

Throughout my childhood I spent a lot of my time with my grandpa who lived a hill away from me with his sister, my great aunt, and his daughter, my aunty. My grandpa and great aunt were both widowed and being at their home was a mix of somberness and politeness, and yet also filled with love.

After dinner, my grandpa, great aunt, brother, and I would watch the Wheel of Fortune TV show and guess the answers. Then my grandpa would go to his room and turn on his karaoke machine. He loved singing Japanese enka songs in his room. I never went into his room to watch him sing. Even though I didn’t understand Japanese and could not understand what he was singing, I could hear the sadness and longing in his voice. I would fantasize he was singing to my grandma.

My grandpa and I had similar energies where we could be quite friendly and outgoing, but predominantly we were introverted. I would quietly observe him day after day playing the solitaire card game. Finally one day I asked my grandpa if I could play solitaire. So he taught me. Then the routine changed and we would sit quietly across the table together playing solitaire before dinner. On one occasion, I asked him, “What does Chiyoko mean?” He didn’t know. Instead he grabbed a piece of paper and wrote my name in Japanese kanji for me to have.

Since my grandpa didn’t know what my middle name meant, I looked it up on the internet. I found that Chiyoko meant “the child of a thousand generations.” Seeing the definition of my name on the computer screen again brought pride and pressure to me. I knew I was named after my grandmother for a reason and again felt connected to her. But could I live up to that name, and make the generations before me proud? Could I become a strong woman like my grandmother?

This brings me to this year. I was a 29 year old woman living in Seattle, Washington feeling completely confused about what to do with my life. For the past two years, something started stirring in me that told me I needed a change. Therefore I started trying a lot of new things. I started to test myself physically again. I went back to judo, a sport I once excelled in. I entered my first tournament in over ten years. I was surprised to be paired to fight with a 17 year old in which I lost. My ego was hurt but when I looked at her, I saw that she was me when I was 17. I could see her love and desire for the sport that I no longer possessed. I was proud of myself for trying but realized it was no longer my calling.

At the same time, I decided to apply to a Ph.D. program. I was terrified. Instead of taking a year or two to research graduate programs and prepare like my peers, I rushed through the process in three months. I was sure that once I made a decision, the universe and my grandmother would grant me what I wanted. If I got into a Ph.D. program, my destination would be set for the next few years and I could move closer to my family in California.

In April, everything started to hit me. I got the news that I was waitlisted from the Ph.D. program. At the same time, a friend of mine passed away. I called my family, crying over the phone, upset at the cards I was dealt. My father assured me that patience was the key and the timing was not right. That is not what I wanted to hear. I was angry. I didn’t want to wait any longer. I prayed to my grandmother for guidance. Why didn’t I get what I wanted? What am I meant to do? What is she trying to teach me?

After the storm of April in my life, I decided to let go of the pressure I put on myself. I didn’t know what was next for me and frankly, I didn’t want to know anymore. Then opportunities started to occur. I was surprised when my boss asked me to attend a conference in Washington D.C. in June. Then another boss offered me to attend a leadership training in July.

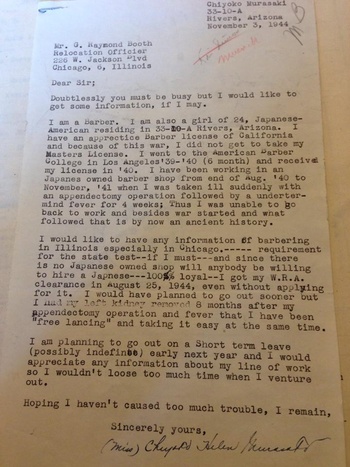

When I went to Washington D.C. in June for work, I knew I had some personal business to do involving learning about my grandmother. The U.S. National Archives in Washington D.C. had records of the Japanese WWII internment files and I decided to go there to find my grandmother’s file during WWII at the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona.

I was not expecting the overflow of emotions that came over me to read the Japanese internment files of my grandma who was around my age at the time. Even while she was put in this unjust place, she wrote letters to the camp administrators asking if she could relocate to work as a barber and would anyone hire a Japanese woman. Over and over she would get rejected, but she kept trying. This added another layer to my family’s story because I realized she must have encouraged my grandfather to become a barber after the war. Together, they were able to open up their own barber shop in Los Angeles. This proved to me her tenacity and savviness to get what she wanted.

In July, I went to Los Angeles to attend a leadership training for Asian Pacific Islanders in my career. The leadership training allowed me the opportunity to reflect and assess my life and where I wanted to be, and to meet mentors who showed me how to get there. It made me see my values and how important it is for me to have the strength of my family and community. If my grandmother could be in an internment camp, in poor health, facing racism, and could still go after her goals, then I too can accomplish my goals. As I said my good bye to my mentor, she took me aside and said, “You’re ready for a change. I’m sure you’ll end up back here in California.”

Perhaps my grandmother saw that I learned my lesson because things started to change. When I returned to Seattle from the leadership training, I received an email to apply for a job in California. Then very quickly and unexpectedly, I was offered the job and was making arrangements to leave Seattle to return to my family in California.

When I moved to Seattle six years ago, my grandfather gave me a card wishing me luck and awaiting my return. Since then my grandfather has passed away and I think about how he has impacted me. As this past year has been a personal journey for me to discover what I want, to be comfortable with fear, and push through my fear for change, I have called upon the strength of my grandfather and grandmother. I now understand why I am named Chiyoko, “child of a thousand generations,” and walk with courage to know my grandparents are always with me.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee Selected this article as one of their favorite Nikkei Names stories. Here are the comments.

Comment from Susan Ito

This piece reflects the bond between a granddaughter and her Japanese grandfather. Although they do not share a common language, I was moved by the scene in which she listens to him singing karaoke in Japanese, and can hear the longing in his voice. When she questions him about the origin of her middle name, Chiyoko, he responds by writing it out in kanji. She later learns of the strength and tenacity of her grandmother and draws upon that as inspiration to persevere during challenging times. She finds that being a “child of a thousand generations” means drawing inspiration from her ancestors and family as she grows into the future.

Comment from Andrew Leong:

Chanda Ishisaka reflects upon mortality and living on, the burdens and the strengths of a name that means “child of a thousand generations.” Brave in its description of difficult emotions of grief and hard-earned realizations, Ishisaka’s story celebrates what is given by a name, without falling into sentimentalism.

Comment from Tamiko Nimura:

Chanda’s essay explores the question of Nikkei names, taking the question beyond simply “how did I get my name?” but deeper, into the question, “how will I carry the legacy of my name with me?” It is notable for the transformation of its speaker and its ability to convey scenes with just the right amount of detail (for example, the grandfather singing enka while the grandkids watching Wheel of Fortune is a great scene). I also appreciated how this essay speaks across generations.

© 2014 Chanda Ishisaka