Read Part 6: Japanese Americans in Southern California - Part 2 >>

The various Japanese American groups that appeared in Los Angeles

In the previous issue, we introduced how Japanese who immigrated to Los Angeles resisted anti-Japanese pressure and organized the "Southern California Central Japanese Association" to protect their rights, and played a role in that organization until the start of the war. In addition, various Japanese-American organizations were established and were active in Los Angeles in various fields, including economy, education, and religion, from before the war through the postwar period, and even after the war.

Below, I would like to introduce the roles and activities of these organizations, which are summarized in detail in the "Centennial History."

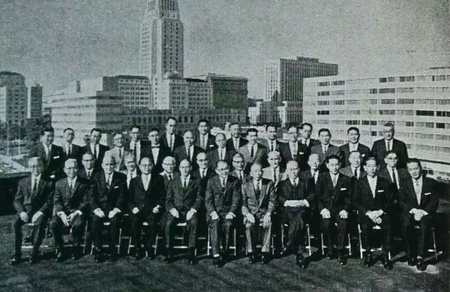

The most representative of these organizations was the Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Southern California, which was established in September 1949, four years after the end of the war, and held its first board meeting on September 13th at the Miyako Hotel.

Its purpose was stated as follows: "The Chamber shall have as its primary objective the promotion of the economic, social and general welfare of all Japanese Americans residing in Southern California by encouraging quality products, skills and services and by fostering good citizenship (Article 2)."

In addition to its functions, the organization also had a trade department, an agriculture department, a social department, a culture department, an education department, a lecture department, a general citizen department, and a youth department. The following are listed as "Nissho's services".

- Assistance with filling out naturalization applications

- Assistance with establishing permanent residence

- Foreigner address registration assistance

- Receiving visitors from home country, guiding them around, and holding welcome parties

In addition, since the end of the war, she has been collecting and sending out supplies and donations (50,000 dollars) to help Japanese war refugees. She also provides consultations and translates letters for Americans who have left their war brides behind in Japan.

The first barber was in 1900

The history of Japanese inns and hotels being run by Japanese people is long, with the Rafu Japanese Inns Association being organized in 1906. Before the war, 360 establishments, including hotels, were members of the association, and even after the war in 1947, there were 400 business operators. In 1949, the Rafu Hotel and Apartment Association was formed. "The association aimed to make economic advances by purchasing various items at low prices and reducing expenses, and since its inception, it has set up research departments for laundry, linen, soap, etc., which have helped to streamline the management of business operators."

Looking at the history of Japanese barbershops, the first one was opened in San Francisco in 1891 by a barber named Nishijima Isamu, and in Los Angeles in 1900, a barber from Hiroshima named Yanagi Kikutaro opened one on Los Angeles Avenue in Plaza Park. The Rafu Barbers Association was founded in 1910. At the association's heyday in around 1939, there were over 80 barbershops. By 1960, that number had dwindled to 33, with nearly half of the employees being second-generation Japanese.

A prefectural association dedicated to the welfare of fellow natives

The Centennial History details the Prefectural Association as "an organization second only to the Japanese Association." Originally organized for the purposes of social interaction and mutual assistance, Prefectural Associations later took on a political nature, such as by serving as the electoral body for the Japanese Association's executive elections, which at one time caused friction between Prefectural Associations.

After returning to its original purpose, in the 1930s it also began to take care of things like "helping the elderly and needy of the prefecture's residents and funerals for those with no relatives." There were many prefectural associations established by around 1915, including those in Fukuoka, Wakayama, Hiroshima, Okayama, Yamanashi, Yamaguchi, Tokyo, Chiba, Nagano, Ehime, Kumamoto, Miyagi, Fukushima, Tottori, Okinawa, Aichi, Fukui, Ibaraki, Gifu, Tochigi, Shizuoka, Iwate, Shimane, and Oita.

Looking at the number of members in each prefectural association in 1926, Hiroshima had by far the largest number with 1,200 members, followed by Wakayama, Kumamoto, and Kagoshima with 400 each, Fukuoka with 350, Okayama with 300, and Fukushima with 200.

After the war, as the second and third generation grew, there was an atmosphere that "it's too late for a prefectural association now," but the need for a prefectural association arose to "take care of needy prefectural residents and funerals, provide relief to disaster victims in hometowns, and welcome visitors from Japan," so it was reorganized around 1950. To promote friendship again, the picnics that were popular before the war were revived and were a huge success.

In addition to the prefectural associations, some groups have changed their name to "XX Clubs," and they are very active, with 20 groups having been organized as of 1960, just before the publication of the Centennial History.

Women's groups also award fertility prizes

Women's organizations were also established early, with the "Rafu Japanese Women's Association" organized in 1904. Many other women's associations were subsequently established under prefectural associations, religious organizations, etc. The "Japanese Women's Association of Southern California," which changed its name and continued into the prewar period, was involved in a wide range of activities, including promoting friendship between the United States and Japan.

One unique postwar project was the "Child-Bearing Mothers Awards," which recognized 52 mothers who lived in Southern California and had more than 10 children, and awarded prizes such as the "Child-Bearing Seven Lucky Children Record" (recorded by Toyotake Yoshitayu).

Other organizations include the Southern California Gardeners Association, which was founded in 1938 as a union for the gardening business, a specialty of Japanese people. The gardening industry began around 1900 with work such as weeding and mowing lawns. A survey in 1905 found that there were 179 Japanese gardeners in Los Angeles, and the number has since increased, leading to economic growth. By around 1946, after the war, the number had reached 3,000.

Other than these, various religious groups have a large presence, including Christian, Tenrikyo, Seicho-no-Ie, Konkokyo, and Sekai Kyuseikyo (Buddhism is introduced elsewhere).

One unusual move was the launch of the "North American Hyakudokai" in February 1984. The decision to establish the group was made at a welcome party held in September of the previous year for the former Minister of Education and Hiroshima University President, Tatsuo Morito. One of the founding members was Shinichi Kato, editor and author of "Centennial History."

(Note: Honorifics have been omitted. Quotations have been made as original as possible, with some modifications. Place names are based on the notation used in the "Centen-nen-shi.")

© 2014 Ryusuke Kawai