Read Part 2 >>

In the late 1970s, the American hibakusha continued their fight for retribution in front of the federal government to no avail. By 1978, numerous bills had been introduced by 25 to 30 members of Congress but none were ever passed.1 Behind all of these rejections was the continuing idea that the American hibakusha, “were part of an enemy nation at the time of the bombing.”

When discussing any form of aid provided by the U.S.A. towards all atomic bomb victims it has been speculated that, “whoever provided medical care to the survivors would be accepting moral and historical responsibility for what had happened to them. Hence the American insistence that the Japanese government be the ones to make treatment available.”2 This idea may also be applicable to the American hibakusha, who would eventually have to rely upon the Japanese government for their financial aid.

While the federal government could not justifiably declare that they did not have enough money, as they had up to that point spent over $80 million just studying the effects of radiation on the hibakusha in Japan,3 they did have other reasons. The most notable reason was the longstanding policy of the American federal government to not give out money, “on an ex gratia basis, arising out of the lawful conduct of military activities by US forces in wartime;”4 since no American hibakusha or activists ever even claimed that the bomb was in any way illegal or unnecessary, they were prohibited from using the Federal Tort Claims, under which they could sue the government for damages inflicted by the U.S. government.

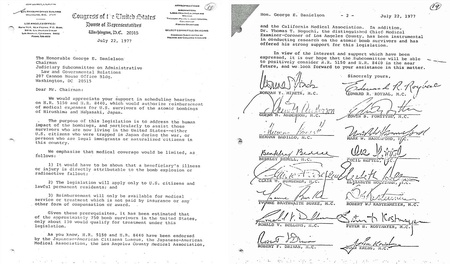

In order to circumvent this policy, the American hibakusha activists began to integrate the idea that there was a “moral obligation”5 for the federal government to provide free healthcare. In addition, Congressman Norman Mineta added that the usage of the atomic bomb made the case of the American hibakusha a special one, one that garnered financial compensation from the Federal government.6 Although this argument may have appeared to be a potent argument to the audience of the subcommittee meeting, which was composed almost entirely of the movement’s supporters, the American federal government’s notable lack of understanding with regards to the effects of radiation may have detracted from Congressman Mineta’s argument.

Notable confusion with regards to the effects of radiation can be shown through the hearings of the “atomic veterans” (veterans who had been sent into Hiroshima just days after the bomb) and “downwinders” (Americans who were exposed to radiation as a result of being near a test site, as well as American uranium miners); as well as in the American media. While the veterans and “downwinders” couldn’t be rejected due to the idea that they were part of an enemy nation, the American government instead claimed that their illnesses were not necessarily caused by radiation.7 It was not until 1988 that the American government would detract this (now known as being inaccurate) argument and pass the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act compensating both of these groups, but not the American hibakusha.

The American media served only to further convolute the already enigmatic atomic bomb. The government even had a hand in this obscuration, “Beginning in 1945, United States officials prevented wide distribution of most images of the bombs’ destruction, particularly of the human havoc it wrought, and suppressed information about radiation, its most terrifying effect,”8 although later in the 1950s and ’60s with the explicit images from the Korean and Vietnam Wars, the realistic images of sufferers would be openly displayed through the American media, the same cannot be said about the atomic bomb. In addition, the general enormity of the bomb made it impossible for it to be properly understood and shown through the somewhat censored media.

The confusion surrounding radiation and the bomb could to an extent also be seen in the experiences of the American hibakusha. In the previously mentioned letter from Mr. Featherstone, written in 1978, to Mr. Kuramoto, he does claim that it would be difficult to, “singl[e] out and determin[e] the relationship of the A-bomb experience to current health problems.”9 This statement in the letter is quite inaccurate because in 1971, Dr. Noguchi had in fact proven that many of the American hibakusha were suffering from radiation related illnesses; he did so by introducing a document that would be unanimously passed by the California Medical Association.10 Despite this, Mr. Featherstone and others within the government during the late 1970s still have felt that radiation had not necessarily caused the American hibakusha’s (or the “atomic veterans”/“downwinders”) illnesses. Although arguments like Mr. Featherstone’s may not have appeared in the actual hearings of the American hibakusha there still may have been an air of skepticism among those who rejected passage of the bill.

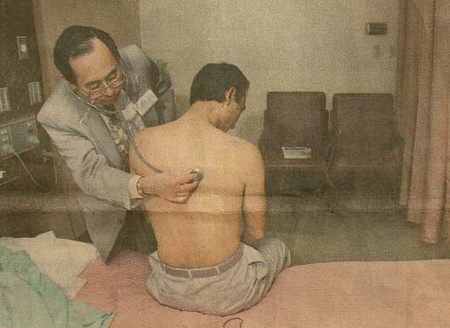

While the American hibakusha would never receive the compensation from the source they thought they would, eventually the American hibakusha employed the assistance of the Japanese government. Japan had already passed a bill by the 1970s entitling all atomic bomb survivors, regardless of nationality, to free healthcare as long as they were living in Japan. Very few of the American hibakusha sought this compensation and remained in their homeland of the U.S.A. paying exorbitant rates for less specialized care. In a movement spearheaded in part by Dr. Inouye, Japanese doctors began coming to the U.S.A. once a year to provide treatment to the American hibakusha. Initially only about a hundred hibakusha claimed this treatment, but over the years it would expand to include nearly all of the American hibakusha. A few of the American hibakusha, those who needed extensive treatment, were sent to Japan for free where they could receive treatment from doctors who were experts in radiation related diseases.

These Japanese doctors and the treatment they provided essentially ended the fight for free healthcare from the U.S. government as hibakusha could access all the treatment they needed. In addition, by the 1980s, the American hibakusha felt more American than ever, the bills continued to appear annually in Congress until its main sponsor, Congressman Roybal, took a new position in 1992. In many ways they were also no longer the “lost” Americans, as the American hibakusha began speaking openly at anti-nuclear protests, and served as first-hand witness to the atrocities of nuclear warfare. As Reverend Hamaoka would put it, “In the larger context, the survivors’ goals have been fulfilled.”11

The American government did eventually help the American hibakusha financially, though not directly, by allowing the Japanese doctors to practice medicine in the U.S.A.. However the Federal Government neither apologized nor revised their standing that the American hibakusha, regardless of their citizen status, were part of the “enemy nation” when the bomb was dropped. While a bill compensating the American hibakusha may have eventually passed in Congress, especially following the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, the declining fervor on the side of the American hibakusha keeps this notion as mere speculation.

Throughout all of the hearings the American government remained skeptical of the effects of radiation and consistent in viewing the American hibakusha as members, during WWII, of an enemy nation; which ultimately prohibited any form of direct compensation. While both Dr. Inouye and the American hibakusha’s routes to attaining their goals came with unexpected challenges, only Dr. Inouye achieved the full American dream. He did help to lobby and fight for the American hibakusha but in the end they achieved what can only be described as an incomplete victory.

Notes:

1. Transcript of H.R. 8440 from Dr. Inouye’s collection, p. 20

2. Lifton, p. 309

3. “The American Hibakusha,” Race, Poverty & the Environment (online; jstor, 1995), http://www.jstor.org/, 4.

4. Letter from Mr. Featherstone from Dr. Inouye’s collection, p. 1

5. Transcript of H.R. 8440 from Dr. Inouye’s collection, p. 103

6. Ibid.

7.Harvey Wasserman and Norman Solomon, Killing our Own: The Disaster of America’s Experience with Atomic Radiation (New York: Delacorte Press, 1982), 3.

8. Hein and Selden, p. 4

9. Letter from Mr. Featherstone from Dr. Inouye’s collection, p. 1

10. Sodei, p. 118

11. From interview in Sodei, p. 119

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Davenport, John. The Internment of Japanese Americans During World War II: Detention of American Citizens. New York: Chelsea House, 2010.

This book is a part of the renowned “Milestones in American History” Series, and is only used for the primary sources that it provides.

Hein, Laura Elizabeth, and Mark Selden. Living with the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997.

A vast range of authors and researchers compiled this book, though Laura Elizabeth Hein and Mark Selden are labeled as the main authors as they put together the collection. The book is a valid source and even is reviewed on jstor.org.

Lifton, Robert Jay, and Greg Mitchell. Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial. New York: Putnam's Sons, 1995.

This book was written by two of the world’s foremost experts on all aspects of the atomic bomb, from the psychological effects on survivors to the governmental aspects. The book is also widely cited and a follow up to Robert Jay Lifton’s Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima, which won the 1969 National Book Award in Science.

Sodei, Rinjiro. Were We the Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima. Boulder, C.O.: Westview Press, 1998.

This book serves as an expanded and somewhat updated version of his section in Living with the Bomb, and much like the previously mentioned work the book integrates copious amounts of primary sources. In addition in the paper only uses the primary sources and recounted information gathered from interviews that are provided by the book.

Wasserman, Harvey, and Norman Solomon. Killing our Own: The Disaster of America’s Experience with Atomic Radiation. New York: Delacorte Press, 1982.

This book, co-authored by the renowned Harvey Wasserman, includes thorough footnotes and is only used for one piece of information that is completely viable.

Yoo, David. Growing up Nisei: Race, Generation, and Culture among Japanese Americans of California, 1924-49. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

This book, which is published by the University of Illinois Press, is a legitimate source. In addition this source is only used in the paper for its quotations from Japanese Americans.

Online

Unspecified author, “The American Hibakusha.” Race, Poverty & the Environment, Vol. 5, no. ¾ (1995), BURNING FIRES: Nuclear Technology & Communities of Color 4. http://www.jstor.org/.

© 2014 Jordan Helfand