My parents are Japanese (my father is from Kagoshima; my mother from Ehime), which firmly rooted my sentiments towards Japan until I was able to travel there myself.

I used to dream of finding my father’s family, but that dream was only a fantasy with the high cost of travel, lodging, learning the language, and limited income as a public employee. As a professional and government official in Peru, I had a low salary just like all public employees. My wife’s job as a teacher allowed us to live comfortably without major financial problems. We lived in [the town of] Madre de Dios (Mother of God), and we would vacation with the entire family in the capital (Lima), staying in our own place there. Our ability to travel became complicated when our family expenses increased when my older children entered college.

In November 1990, I left behind job security and decided to travel to Japan with my older brother.

The impulse behind this decision can be traced to August 7, 1990, when the then-Prime Minister and Minister of the Economy, Juan Carlos Hurtado Miller, announced the “Fujishock,” using the words “May God help us.” From midnight onward, the price of gasoline increased thirty times what it was the previous day, while the price of bread, milk, etc., also went up. All of this happened because most of the Peruvian economy had been subsidized under the former president, Alan García, causing hyperinflation. I had a stable job, a high position in government, with a spouse who also had a good job, which allowed us to survive. Now I had to make a decision.

Encouraging us towards this new adventure was the fact that we had the family’s koseki (Japanese family registry) because several relatives were already working in Japan. We had money to cover travel to Japan and the domestic travel necessary to get to Lima. The problem we faced was how to establish our birthplace since my father’s Christian name (Antonio) appeared on our documentation rather than his real name (Kinsuke). Discussing the situation with several of our fellow countrymen, they offered a solution: erase the Christian name and use his real name instead. We took their advice and arrived in Lima.

The hiring official reviewing our documentation did not realize that we had changed the name; soon we were hired to work at a factory. The company, which had financed our trip from Lima to Narita, provided us with free housing, subsidized 50% of our meals, gave us a salary of 1,250 yen an hour (between $10 and $11 an hour), overtime pay, an incentive of $1,500 for not taking any sick time, an additional $3,000 for services rendered, and an offer to pay 50% of a return ticket home if we decided to go back to Peru before the end of our contract. We could walk to work in fifteen minutes. Without much effort, I received a monthly salary of $2,800, which allowed me to remit 40% of it to Peru to help my family there. It was a golden age for us.

On December 3, 1990, thirty Peruvians—all of us supposedly Nikkei—started our journey, traveling via Miami to the airport in Narita. Company representatives met us at the airport and took us to Shonanday-Fujisawashi, Kanagawa-ken, about 45 minutes from Tokyo, where the satellite office was located. I remain grateful to the IZUSU company for what it did for us, although the hope that I had for the future gave way to the global economic crisis.

For a Nisei like myself to walk on Japanese soil was a dream come true; I even cried because it was such an unforgettable experience. Peruvian Nikkei are considered Japanese in Peru, but we never knew that the Japanese themselves would treat us as simple foreigners (gaijin).

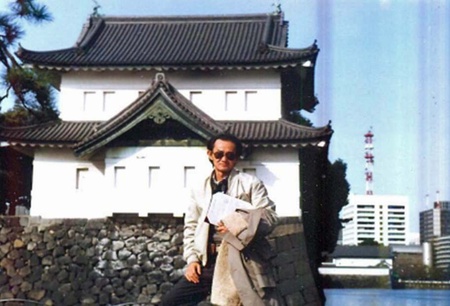

The building in the background of the following photograph belongs to the Imperial Household in Tokyo.

The company put us up in housing that had a store, restaurant, pool, and a hair salon. While our visas were being processed, the company helped us with food and housing. Nevertheless, the delay was unbearable as days passed; we were unable to work. Two weeks later they discovered that one of our Peruvian companions had falsified documents, and he was deported immediately. After thirty days in Japan, we were officially hired by IZUSU; fifteen of those days we spent training and learning about our new jobs and the company.

After about three months, we appeared before the immigration officials in Tokyo and received the bad news that we were being given the APPLICATION seal, which is a red seal that indicates the date of return to one’s country. Our documentation had raised questions, and we had ninety days to leave the country. As the hiring official had a financial stake in us (roundtrip airfare, food, insurance, etc.), he continued to follow up with us until we had paid off our debts. Finally, the day arrived—June 30, 1991—we were taken to the airport in Narita so we could leave Japan. We felt like deportees.

Only one of us received a visa; someone who didn’t even have Nikkei facial features but who, nevertheless, had submitted the appropriate documentation. Of the thirty Peruvians who traveled to Japan, about 20% had Asian features and only two (my brother and I) had a Japanese father and mother. Ironically, we also had “bad documents.”

My six-month plus stay in Japan was an unforgettable experience. I didn’t know the language but that didn’t stop me from traveling by train to Shizuoka, Tokyo, Yokohama, Tochigi, Gunma, etc., or to take the shinkansen, go shopping for the latest American technology, visit with my Peruvian relatives, etc. I was unable to visit my relatives in Kagoshima, however, because I didn’t know the language and had to save my money. One of my nieces had traveled to Kagoshima and located one of my father’s relatives.

As a legal descendant who considered himself Japanese, I was outraged and angry at myself and at the Japanese for not having given me a visa. I was even mad at the Peruvians. In neither country did I seem welcome. In Peru, they call us “Chinese,” “slanty eyes,” “dish face,” etc., disrepectful words that hurt and cut deeply. In light of being rejected for a visa and by Japan and Peru, it was understandable that such sentiments would flourish, including whom to blame (human nature never recognizes its errors and casts blame on others).

I blamed my father for having been baptized a Christian and changing his name; I also blamed myself for the choices that I had made when preparing the paperwork. After much moral suffering, I told myself that I would never return to Japan. By the end of the year, however, after thinking it over for some time, I told myself that I was to blame. I met with a lawyer who initiated the proper procedures to correct my birth certificate (obtaining a judicial decree that stipulated my father’s real name).

More than twenty-three years have passed since my attempt to emigrate to Japan. At times the desire to return to Japan comes back, but this time only for vacation. We know that the financial crisis also affected Japan; the golden age of the 1990s is over. Many Peruvians have returned to Peru, although we pine for the days of prosperity, when someone’s word, honor, discipline, and honesty meant something; where technology is present; and above all, a secure country where you can walk anywhere at anytime without being assaulted. Peru is no longer a very poor country, but it still has critical problems: insecurity, organized crime, delinquency, etc., that gets worse without any solutions from the government.

© 2014 Santos Ikeda Yoshikawa