“Years of media abetted conditioning to the possibility of war, invasion, and conquest by waves and waves of fanatic emperor worshiping yellow men,” the late writer Michi Nishiura Weglyn pointed out, “invariably aided by harmless seeming Japanese gardeners and fisherfolk who were really spies and saboteurs in disguise—had invoked latent paranoia as the news from the Pacific in the early weeks of the war brought only reports of cataclysmic Allied defeats.”1

Indeed, even before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and internment, the U.S. government questioned the loyalty of its Japanese citizens. The F.B.I. and Naval intelligence had performed exhaustive surveillance of the Japanese minority and 72 years ago last month, state department official Curtis B. Munson submitted his federally commissioned report in which he conducted a secret survey measuring Japanese and Japanese American loyalty to the U.S. Though the Munson Report found a “remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty” among Japanese Americans, State, War, and Navy departments nonetheless promoted internment policy with Henry L. Stimson leading the way.2

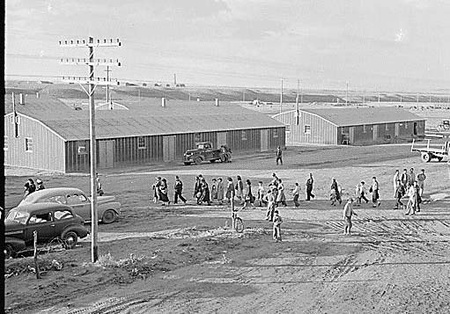

Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming. One of the last groups of arrivals, at this relocation center, cross the warehouse area from the railroad platform to the registration office. (Photo from the US National Archives, #538788)

The Munson report serves as a useful reference and departure point for the place of Asian Americans in pre- and post-WWII America and the kind of odd racial dynamics at play in a nation wedded to black-white binaries of racial understanding.

Moreover, in the years following internment, SoCal Asian Americans fought housing segregation, battling for their own suburban dreams and demonstrating how foreign policy, shifting demographics, and the Cold War all combined to open up new venues for Asian American homeownership but failed to deliver the same opportunities to black Americans. Few places embodied this complex amalgam of domestic tensions and foreign policy like Southern California.

As has been documented by numerous scholars, from the late nineteenth century through the Second World War, state and federal law had long discriminated against Asian Americans. Western states adopted Alien Land Laws preventing Asian American property ownership while federal immigration policies reduced the flow of newcomers from Asia to a veritable trickle. With the rise of Imperial Japan in East Asia and its expansionist policies of the 1930s along with the U.S. occupying the then-territory of Hawaii, many federal officials viewed the island empire as a threat to U.S. interests.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, fears regarding spies and foreign invasion, stoked by the media, inundated the public. In Los Angeles just prior to American involvement in WWII, even real estate brokers and white homeowners had begun to deploy the language of “invasion” to limit Japanese American homeownership, thereby handcuffing the rights of Nisei citizens.

A sign that states "No More Japanese Wanted Here," in Livingston, Califonia around 1920 - 1930s. (Gift of the Yamamoto Family, Japanese American National Museum [98.54.22])

Jefferson Park 1940 – 1941

In the late 1930s, few housing markets received more attention from the FHA than California. “Because of … recent residential building activity (primarily under F.H.A. type financing),” reported field agent T.H. Bowden and analyst D.W. Mayborn, “it is believed that the homeownership rate is now substantially larger than 1930, possibly as high as fifty percent.”3

Unfortunately for Los Angeles’s non-white residents, the FHA largely excluded minorities from its program. Even ethnic whites like Southern Italians and Russians or religious minorities like L.A.’s Jewish population endured discrimination via federal policy. Yet, to Los Angeles assessors, who occupied a key place in FHA and HOLC policy making, blacks and Asians remained the most pressing threats to neighborhood housing values. Federal policy makers viewed racial and ethnic heterogeneity as problematic and purposely rated communities with such diversity as poor investments for private financing, thus establishing an institutionalized system of discriminatory lending that private capital followed rigidly.

Though ethnic whites and many Mexicans endured housing discrimination, “social class, occupation, and skin color provided a ladder to whiteness” for segments of these populations, notes Charlotte Brooks in her study of Asian American housing integration, Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California. For blacks and Asian Americans, no amount of income could reconcile their racial difference. As one surveyor put it, the best sign that homeowners “remained ‘low class Southern Europeans’” rested on their communities’ proximity to non-whites.4 Obviously, the diversity of Central Los Angeles presented surveyors and homeowners with obstacles as assessors frequently highlighted the problematic heterogeneity of these neighborhoods and their pockets of Japanese and black populations.5

In 1938, a group of business partners led by two white businessmen, William Cannon and Ralph Edgerton, created the Pacific Investment Company (PIC) and secured FHA underwriting for a new tract home development for Nisei near the Baldwin Hills oil fields and La Ballona Creek. As a sign of the land’s marginal status, the PIC paid only $35,000 for the property and assessors rated the surrounding districts poorly. Even with these caveats, Nisei Angelenos enthusiastically signed up for a chance at homeownership and a better standard of living, both denied their Issei parents.6

Nearby West Adams had already riled up local white homeowners. Restrictive covenants in the community had expired, enabling Japanese and black integration. Arlington Boulevard served as the racial dividing line, and the local West Adams homeowner association continued to fight against non-white newcomers. When the FHA approved the PIC development, it more or less ensured racial transition of West Adams and the FHA’s intent to contain non-white community expansion.7

Furthermore, in a demonstration of how abstract conceptions of whiteness and the FHA’s protection of segregation affected relations between aggrieved minorities, many Jewish Angelenos residing in West Adams, approximately half the community, believed city elites did little to prevent the transition because of Los Angeles’ “casual anti-Semitism” and “Nordic ideology.” Ultimately, FHA policies fueled such reactions since the organization established clear linkages between property values and segregation.8 Though having once been targeted for housing exclusion by Christians, some Jewish residents now internalized the racism of FHA policy in an effort to protect their home investments.

Likewise, when Japanese Americans discovered Jefferson Park’s racial restrictions specifically excluded blacks but allowed for Asian Americans, Nisei elites obscured this knowledge from public view to secure support from African American outlets like the Los Angeles Sentinel.

Some historians have argued that this “sin of omission” demonstrated Japanese Americans’ own racism toward fellow minority groups. In this way, John Modell has noted, Nisei still would not qualify as white but could distinguish themselves from other minorities. Others, like University of Michigan’s Scott Kurashige have argued Nisei acceptance of these restrictions reflected class bias, not racism. Often, the U of M historian argues, Nisei looked down upon “lower class Japanese Americans and other Asians [more] than their educated black and Mexican peers.”9

Whatever the case in this instance, the fact remained the Nisei investors did not set the terms; racial restrictions had been the purview of the developer. Already suffering from marginal citizenship, Nisei could do little to alter policy. In fact, white homeowners even challenged their own failure to include Asian Americans within the restricted groups, as many pointed to state miscegenation law that banned marriage between Asians and whites. Whites feared the threat of interracial romances that many equated with housing integration.10

Still, this opposition could not simply deny prospective Nisei homebuyers as they had Asians in the past, since Nisei unlike their Issei parents and grandparents were citizens. In previous decades, local elected officials and homeowners could deny Asians certain rights, particularly the ability to own land, due to their lack of citizenship, which of course Issei could do little about since federal law prohibited their naturalization. Instead, local council members and residents deployed the language of “neighborhood invasion” amidst possible war in the Pacific to persuade the city council to “ignore the rights of Nisei citizens” and deny Japanese American efforts to integrate Jefferson Park. The language of invasion played no small part. “As the U.S.—Japanese relationship deteriorated,” notes Brooks, “these words began to convey something even more troubling: whites’ equation of what they called neighborhood ‘Jap invasion’ with actual Japanese invasion.”11

Internment followed soon after. Despite the aforementioned “Secret Munson Report,” which noted a great deal of anti-Japanese fervor related to white farmers coveting Japanese American land and resenting competition, U.S. officials rounded up the minority group and placed them in concentration camps in the American West. Of the 127,000, Japanese Americans living in the continental US, 112,000 lived on the West Coast, 93,000 in California alone.12

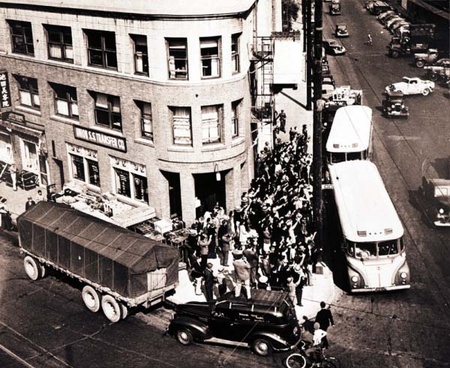

Japanese Americans gathering in front of Nishi Hongwanji Temple in Little Tokyo to get on the bus heading to the assembly center. (Gift of Jack and Peggy Iwata, Japanese American National Museum [93.102.102])

Needless to say, US wartime propaganda depicted the Japanese as morally questionable and untrustworthy. When the war ended, however, so too did the need arise to change American ideas about Asian Americans. Certainly along with their black, Latino, and Native American counterparts, Asian Americans contributed mightily to the war effort. Still, even military service only brought these groups so close to full citizenship. For Asian Americans, the ensuing Cold War also helped. After all, with the communist threat looming and the Cold War just gearing up, American officials and the public realized the need to put on a good face for an international community that it hoped would side with the United States in future conflicts with the USSR, particularly in Asia.

If Jefferson Park demonstrated the boundaries that still prevented Japanese and Asian Americans from enjoying full equal rights, housing controversies of the 1950s illustrated new realities. Not only had international politics impacted local concerns, so too did demographic change driven by WWII. Blacks and Latinos, mostly Mexican Americans spurred on by the Bracero Program, rapidly increased their numbers in Southern California. Though Los Angeles assessors had considered blacks and Asians of equal threat to property values in the 1940s, by the 1950s the increase in SoCal’s black population ratcheted up white fears. Within this dynamic of Cold War politics and changing demographics, African Americans found themselves enduring the most pernicious housing discrimination, while Asian Americans enjoyed new opportunities, but not without facing a reactionary formidable opposition in both Northern and Southern California.

Notes:

1. Michi Nishiura Weglyn, “The Secret Munson Report”, in Asian American Studies: A Critical Reader, Eds. Jean Yu-We Shen Wu and Thomas C. Chen, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010, pg 195.

2. Ibid. pgs. 194-195.

3. Charlotte Brooks, Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009) pg 116

4. Ibid, pg 117.

5. Ibid, pg. 117.

6. Ibid, pg. 118.

7. Ibid, pg. 119.

8. Ibid, pg. 120.

9. Ibid, pg. 123.

10. Ibid, pg. 123.

11. Ibid, pgs. 125 – 127.

12. Michi Nishiura Weglyn, “The Secret Munson Report”, in Asian American Studies: A Critical Reader, Eds. Jean Yu-We Shen Wu and Thomas C. Chen, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010, pg. 195.

*This article was originally published on TROPICS OF META on November 11, 2013.

© 2013 Ryan Reft