Read Part 2 >>

There’s a model of the city before the bomb, a bustling metropolis of about 350,000 with a good reputation for higher education, and a military base.

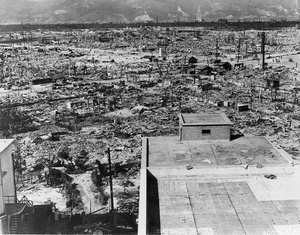

While the pictures of the physical damage to Hiroshima are devastating, I’ve seen similar ones of the aftermath of the bombings of Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Fukuoka, and Sendai that show a similar scale of physical destruction as unimaginable as it seems today. In March 1945, Tokyo was fire bombed for two hours, leaving 16 square miles of the eastern side of the city destroyed; 88,793 dead, 130,000 injured, a total of 268,000 dwellings burnt down, and a million homeless. For thirty-six hours the U.S. hit Nagoya and Osaka, on March 23, and four nights later, Kobe. Washington, delighted by General Lemay’s success, designated 33 more cities as future targets.

No amount of preparation, study, or pontification, can really prepare one for the displays of A-bomb artifacts and materials in the West Building. The horrible and awesome spectacle records the moment when mankind lost a certain innocence from which it has never recovered.

A moment, no; it’s actually an eternity that’s frozen in time. Here in the chilling artifacts one beholds a watch stopped forever at 8:15, a molten mass of copper-colored metal which was a child’s tiny tri-cycle, shreds of school uniforms ripped away by the blast, the shadow on the steps that remains of someone who was vaporized 260 meters from the hypocenter.

And then there was the rain, the black rain, that fell in the maelstrom of the bomb amidst the howls and cries and whimpers and a death-like shock; the black, demonic rain, quenching nothing, useless but deadly, the mocking rain.

Perhaps it’s the perfect metaphor for all of the useless hyperbole and rationalization that led up to that moment and which would haunt us for the rest of the century and, undoubtedly, for eternity.

The truth of human nature is…? There is no getting away from the fact that we possess the capability to unleash this kind of madness upon ourselves. Truly, the monsters aren’t over there, defined by a certain race, religion, creed, or color; we are the monsters, the grotesque masks, the surreal images of human deformity that we usually miss as true glimpses of ourselves. No, they aren’t “over there” somewhere in outer space, in some country you’ll never visit or in some never-never land: they are right here. Once that ancient wisdom sinks in then the finger pointing stops: the “us” versus “them”, the Hate. When you realize that it does not matter that it was them, it could have been us, the madness of comparing sufferings with suffering, as though it were something quantifiable is gone. That for this evil all of humanity owes a compensation to them that absolutely cannot be measured; that is these people, of all people, can forgive, then that has got to be the lesson that we must take away from this most remarkable museum.

I stagger out into the oppressive heat which doesn’t help matters. My mind and heart are a whirl of thoughts and emotions; overcome not so much by the horrors of what was seen but more by the enormity of the love and compassion that is really the message here. We only seem to gain any real insight into who and what we are as human beings when we go to the very brink of despair and suffering.

Close to the park bench where I settle myself is an open wall “YMCA” tent with a group of chanting Buddhist monks in front. There’s a sign in Japanese and English. “Fast For Peace. Non-Nuclear Japan. Non-Nuclear World”.

Directly across is the Atomic Bomb Memorial Dome for the souls of the unclaimed dead. An elderly lady spends a long time lighting incense sticks, one by one, placing them in the urn in front of the altar. She bows slowly and remains in that position for a long time before rising. Then, leaning on a cane, she walks slowly away to be replaced by another elderly woman also stooped over and white-haired with a sun hat. She repeats the silent ritual.

Offerings of long strings of colorful paper cranes sent from around the world are piled up on monuments throughout the park; reminders that there are still many who haven’t forgotten.

I learned about the story of Sadako, a baby girl at the time of the atomic blast who died afterwards from the effect of radiation. During the time of her hospitalization, she believed that if she made 1,000 paper cranes, she would get better. She folded some 1,300 before she died. Sadako is the statue of the young girl at the top of the “Statue of the A-Bomb Children”, with out-stretched arms and a crane. The symbol of happiness and longevity, rising above her.

Later that day, in a shopping area, I pause awhile to rest and watch an animated version of the same scene. The procession of elderly women in front of one monument is replaced by a group of yellow-capped elementary school kids. Their teacher explains the Sadako story. Accompanied by the thud-thud-thud of hand drums, the chanting starts up again.

That night, I meet up with Yoshio Uno. We’d met a year ago last summer at a yamabushi trek in Yamagata. A lot has happened since then. One member of our group, Yasunori, died in a car crash. Senji’s dad passed away earlier this year, too. Yoshio is a high school computer teacher living in Kushiro City, Okayama, while his family lives in faraway Tokyo, a common work/living arrangement in Japan called tanshin funin.

We meet at Hiroshima Train Station and head to “Okonomimura”, three-floors of different counter stalls in a large building. Okonomiyaki is a popular fast food, often described as a Japanese-style pancake, but, while round and made of a flour batter mixture, it’s really more like an omelette.

I have had okonomiyaki in Sendai, but this was entirely different. A batter mix is first spread out on the table-size hot plate counter. The seafood I order cooks on the side, along with udon, vegetables like cabbage and bean sprouts, and bacon. When all of these ingredients are ready, they are placed on the hotcake. An egg is cracked and spread around to form the other side of the round delicacy. A thick, sweet, and tangy sauce is spread over the serving.

These stalls appear to be mostly family-run operations. The one we are at is operated by two Korean sisters and a Vietnamese woman. They are shy and hard working. Cool, I think. Other Asians certainly live in Sendai but they prefer to live behind invented Japanese names and identities; they aren’t as conspicuous as they are in Hiroshima. Uno-san gleefully takes some pictures with the digital camera he recently bought. We betsu-betsu on the bill amounting to about 2,000 yen each, with two beers. Cheap, good fare.

As fate would kindly have it, the sprawling “Nagarekawa” red light/drinking area is a short stroll away. Still hungry, we decide to stop in at a yakitoriya that looks quite inviting. Uno-san has sent me niho-shu from his part of Japan and I’ve done likewise. Yamaguchi-san, the oyakata, makes sure that we are well taken care of in his tiny “Toriyoshi”. We drink five 300 ml bottles of different jizake (local nihon-shu), the graciously inspired names roll off the tongue as smoothly as the heavenly elixir down the palate: Namanama from Takenara; Hotarumai ‘Dance of Fire Fly’ from Saijo; Mine sen-nin namazake from Shobara; then oyuwari, Kyushu shochu, sweet potato alcohol mixed with hot water, umeboshi pickled plum thrown in for good measure and mashed in the drink. It’s nice to get re-acquainted.

We both stumble off in separate directions, he to his cousin’s place and I back to the Chanter Hotel. Tomorrow is the 6th, and we both plan to be up early and at the Peace Park before 8:15 am to participate in the ceremonies.

August 6, Hiroshima

The next morning I am up at 7 a.m. with quite a bad hangover. Nihon-shu always does it. Nothing really helps except drinking lots of cold water, a shower, and rest. I don’t have this luxury today. I go down to the Japanese-style restaurant in the basement of the hotel and have a breakfast of rice, miso soup, grilled salmon, some nori, tsukemono, green tea, and natto. This seems to help. Since the park is only a 20-minute walk away, or so, I don’t have to hurry.

By the time I arrive at the park, it’s busy; groups are gathered here and there, and the large seating area in front of the A-Bomb monument is crowded with dignitaries, politicians. I find a spot on a bench beside two men who look to be in their sixties and wonder if they are survivors? We all wait for 8:15. It’s another hot, humid, sunny day.

I imagine hearing the sound of three B-29s in the distance, with the waking city oblivious of the coming onslaught. I imagine the anxiety of the crew of “Enola Gay”. The pilot, Paul W. Tibbits, navigating to the drop point (I understand his co-pilot went mad afterwards). A push of the button catapults humankind into a most fearful age. The first-hand accounts of hibakusha, the A-bomb survivors, begin with the first “pika”, the flash, or “pikadon”, the flash boom, for those who heard it.

The 15 kiloton bomb (the equivalent of 3,000 B-29 bombers loaded with TNT) exploded 580 meters above Hiroshima and produced a fire ball of millions of degrees Celsius, reaching a maximum radius of 230 meters one second after the explosion. The fireball maintained its brightness for 10 seconds. The temperature of the fireball dropped from 7,000 Celsius 0.1 seconds after the blast to 1,500 three seconds after. At the hypocenter, the ground temperature reached 3,000 to 4,000 Celsius (the melting temperature of iron is 1,550C).

A supersonic blast was created by the rapidly expanding air and the shock wave travelled 740 meters in the first second (the speed of sound is 340 meters a second) and about 11 kilometers in the first 30 seconds, after which it weakened rapidly. The blast in Hiroshima destroyed almost all the buildings and structures within 0.9 km of the hypocenter, everything caught fire and burned and fatally burned within the 1.3km range.

The personal injuries differed depending on where the victim was at the moment of the blast. There is plenty of horrific pictorial evidence. The lucky ones, perhaps, were literally vaporized. Those less fortunate had to endure the unimaginable pain of having eyes, ears and mouths burned away, the flesh burned to a black crisp and death being the only possible relief.

Those who survived, developed “Atomic Bomb disease”. The most serious cases (130,000 to 140,000) died within four months of the blast. Today, there are approximately 237,000 survivors who experienced the bombs (Hiroshima and Nagasaki) directly; 124,000 who were effected by residual radiation and 6,000 who were exposed in utero. Seventy-five percent of survivors still reside in Hiroshima and Nagasaki prefectures. Remarkably, “hibakusha” health-related issues concerning medical costs and care continue even to this day.

8:15 a.m.

8:15 a.m., 55 years later. The moment comes with no fanfare. Instead, I hear the sound of a gong in the main square on the other side of the park, where the official ceremonies are going on. A couple of young guys lay themselves prostrate on the ground, eyes closed, hands pressed together, gassho, in prayer. We join them at that moment united in the hope that this evil will never again be repeated.

There’s a couple of folksy looking guys with acoustic guitars singing protest songs. People mill about the area. But it’s a time for contemplation and inward looking. You can’t get enough of that. I say some silent prayers, then decide to head back to the hotel to sleep off this infernal hangover.

By the time I arrive back at the Peace Park, it’s 6 p.m.—already dusk. Upon entering the park, I’m surprised to see square paper lanterns with a lit candle inside each one, strung along the walkways that weave throughout the park. It’s like walking into a corridor of heaven. On the river bank, there’s a small stage, set-up with some pretty funky jazz, Coltrane, I think, being performed by a group. Once they finish, I see a tuxedoed man carrying a large case. Much to my surprise, it’s the famous cellist Yo-Yo Ma. He plays a familiar sounding piece, one piece only, then he’s off.

There is something solemn about this procession of flickering candles. The crowds are gathered in front of the Atomic Bomb dome. As I get closer to the river I’m amazed again. The procession of candles continues in the river as people place floating lanterns of pale blue, yellow, orange and red onto the water, forming a silent procession of holy light down the river. It is such a simple show, yet spellbinding. In a country where spectacular hanabi fireworks shows are occurring throughout the country at the same time, these silent, precariously fluttering lights carry with them their own simple magic.

It is said that at the moment of death, our lives flash by like an old 8mm home movie flickering in our mind’s eye. The moment “Little Boy” was released from the belly of the B-29, the victims never had that last wish. Unwittingly, the gates of hell opened and the innocent were consumed and vaporized. History can repeat itself despite the checks and balances we set in place, because some irresistible madman comes along every generation or so, pushing the right psychic buttons, saying the right things, tantalizing the masses with the rhetoric, blinding us with our own inflated self worth. We cannot be trusted.

Deep in our own thoughts, we all gather here on this river bank, saying our prayers—mokuso, on this sweltering Sunday evening. We quietly watch their uncertain journey down to the Inland Sea. Slowly disappearing into the depths of the black night, like lost souls who finally secure a chance to go home to rest.

*This article was originally published in the October 2000 issue of the Nikkei Voice.

© 2000 Norm Ibuki