Read Part 5 >>

At the close of our interview, I put this question to Sue. “You said it’s been, or it is increasingly becoming, a form of catharsis for the Nisei generation to talk about their evacuation experiences. Has your involvement in the struggles of the past few years been cathartic for you? If you perhaps disavow the label ‘radical,’ has your entire participation since 1969 in the Manzanar Committee and related activities succeeded in ‘radicalizing’ you somewhat?”

I guess I’ve come out much more strongly since I’ve been working with the Manzanar Committee. I’ve reached the point where I don’t even care what anybody calls me, and I feel that it’s now become part of my life.

I was asked to speak at an anti-war rally as representative of a group that called themselves Asian Americans for Peace. I had never done anything with the group, really, except maybe go to their meetings or fund raisings, and made some donations to them. George Takei [the actor and unsuccessful candidate for a seat on the Los Angeles City Council] insisted that I was the only one that could do it because I had worked on the Manzanar Committee, and he felt that I could articulate myself in terms of relating what was happening in Vietnam with what had happened at Manzanar.

So I spoke for just a few minutes at that rally, which was held in Los Angeles. Then I’ve been on the Education Commission. It’s gotten to the point now where when people say “Sue Embrey,” they automatically say the “Manzanar Committee.” One person said, “Yes, the infamous one!” I guess it has radicalized me more in terms of what I say, although some people say I still say things so that it doesn’t come out that strong, because I don’t use profanity, I don’t use the terminology that the young people use.

And sometimes I become very academic when I say something, like at the 1972 pilgrimage. Later, Warren Furutani said to me, “Boy, you really blew their minds!” And I said, “With what?” And he answered, “Your speech.”

What I had said was that whether Manzanar becomes a landmark or not, it was a symbol. It symbolized the ultimate negation of American democracy, and that was the racism that’s been in the United States. And that even today, while we were there at the pilgrimage, it was going on in Vietnam, with the strategic hamlets and Asians killing Asians, because there were Asian Americans being drafted into the service to fight in Vietnam. And that the people who spend the day there at Manzanar should keep it in their minds that it could happen to someone else, and that I hoped that they would be in the forefront of defending people so that it doesn’t happen to them.”

Clearly Sue’s return to Manzanar in 1969 and her involvement in and leadership of the Manzanar Committee and its annual pilgrimage to the Manzanar site over a period of thirty-seven years were pivotal to galvanizing her self-identity and enhancing her effectiveness in educating and engaging the next-generation activists who fought for wartime redress and civil rights.

Not only was Sue instrumental in Manzanar’s 1973 designation as a State Historic Landmark, but also its being named a National Historic Landmark in 1985. Seven years later, in 1992, thanks in large part to the lobbying efforts of Sue and the Manzanar Committee, the U.S. Congress established the Manzanar National Historic Site.

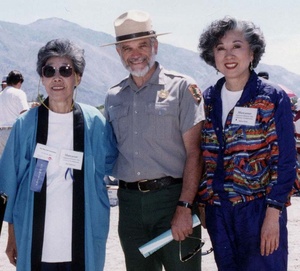

Rose Ochi, the first Manzanar Superintendent Ross Hopkins, and Sue Embrey at the 1997 Pilgrimage, the year that the National Park Service received the deed to Manzanar from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). Courtesy of Manzanar Committee

She thereafter chaired the congressionally-authorized Manzanar National Historic Site Advisory Commission and worked closely with the National Park Service to develop the 813-acre site, the interpretive exhibits, and programs. Moreover, she played a key role in every step of Manzanar’s development, including planning exhibits, publications, film, and education programs.

Fittingly, at the grand opening of the Manzanar National Historic Site Interpretive Center on April 24, 2004, effusive praise was showered upon Sue for her dedication and leadership, along with a standing ovation by the 2,500 people who attended that event. As this event’s keynote speaker, Sue articulately responded to the question frequently put to her of why she believes it is important to remember and keep Manzanar alive with the interpretive center. “Stories like Manzanar,” declared Sue, “need to be told, and too many of us have passed away without telling our stories. The Interpretive Center is important because it needs to show to the world that America is strong as it makes amends for the wrongs it has committed, and that we will always remember Manzanar because of that.”

* * *

Sue Embrey’s wise explanation of why it is important to remember and keep alive the memory of Manzanar applies as well to why it is important to remember and keep alive the memory of the Harada House.

National Historic Landmark, Harada House. Courtesy of the Riverside Metropolitan Museum, Photographer Chase Leland

It is right and proper that we should pay homage in programs such as that being held here today at the Riverside Metropolitan Museum to both the preservation and interpretation of the Harada House on Lemon Street as a National Historic Landmark and the publication of a stellar volume like Mark Rawitsch’s The House on Lemon Street chronicling the origins and evolution of that development.

But we must also make room in our commemorative proceedings for two relevant and instructive historical facts. The first of these facts is that the Harada House would have simply remained a nice boxy house on Lemon Street had it not been for the steely and courageous resolve of Jukichi Harada who, after buying it, refused to cave into his racist white neighbors’ seductive arrangement whereby he would sell the house for a profit and make his home elsewhere in Riverside.

“I won’t sell,” Jukichi stated emphatically. “You can murder me, you can throw me into the sea, and I won’t sell.”

The second of the facts we must remember is that the principled resolve and resistance to racist oppression put into practice so powerfully by Jukichi (who along with his wife Ken died not in their Lemon Street house but an American concentration camp) was passed along to his children. This inheritance was perhaps most forcefully expressed at the time of the 1943 loyalty questionnaire’s administration in the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah when Jukichi’s Nisei son Clark defiantly refused military service in the U.S. Army, saying in effect, “How could his country ask for unbridled loyalty from incarcerated citizens to whom it had shown no loyalty whatsoever?”

The linkage between the actions of Sue Kunitomi Embrey and Jukichi and Clark Harada (and all other Japanese American who resisted unbridled and oppressive racist treatment over the years) is best captured in the conclusion to Diana Bahr’s biography of Sue, when she quotes from a speech given by Sue’s granddaughter Monica Embrey at the April 29, 2006, Manzanar Pilgrimage:

In the fighting spirit of my grandmother, I want to say we young people must learn from the commitment of our grandparents, learn from their perseverance, their strength, and their courage in this great injustice. We must learn not only to endure but also learn that through dedication and determination, injustice can be made right. Our grandmother never said Shigata ga nai. She says Nidoto nai yoni, let it never happen again.

Monica Embrey and her brother Michael on stage at the 2006 Pilgrimage. Courtesy of National Park Service and Manzanar National Historic Site.

* This was a presentation at the Riverside Metropolitan Museum, in Riverside, California, on October 20, 2012, for a program to celebrate publication of Mark Howland Rawitsch’s 2012 book, The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream, published by the University Press of Colorado in the Lane Hirabayashi-edited NIKKEI IN THE AMERICAS series.

© 2012 Arthur A. Hansen