The California State Parks describes the California Missions Trail’s importance as “humble, thatch-roofed beginnings to the stately adobes we see today, the missions represent a dynamic chapter of California’s past. By the time the last mission was built in 1823, the Golden State had grown from an untamed wilderness to a thriving agricultural frontier on the verge of American statehood.”

The history represented by the Spanish missions trail is of European settlement, but it is not the only mission trail in California. There is a missing chapter, pages torn out and forgotten, as the State transitioned from an agricultural frontier toward the social change and urban development of the 20th Century.

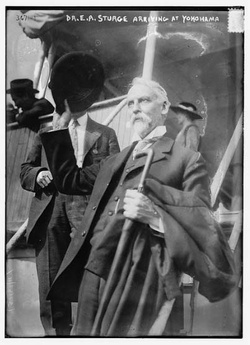

Dr. Ernest Adolphus Sturge, arriving in Yokohama circa 1910-1915, was honored in 1904 with the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Meiji for his work establishing Japanese missions along the West Coast for the Presbyterian Church. Sturge took on the stewardship of Japanese missions in 1886, and was present at the opening ceremony for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He had a close relationship with the Wintersburg Mission's first clergy, Rev. Joseph K. Inazawa. (Photograph, Bain News Service, Library of Congress)

In 1885, the first Japanese mission in California marked the beginning of an effort for a new group of pioneers to establish communities as they assimilated to American life. It is integral to the dawning of Pacific Rim interaction and migration.

While the twenty-one Spanish Franciscan missions were stationed approximately 30 miles apart—a day or two ride by horseback—the Japanese missions sprang up in communities where immigrants established themselves for work. In Orange County, work in the early 1900s focused in the celery and chili pepper fields surrounding the Wintersburg Village, before gradually moving south and east.

In contrast to the Spanish missions, there was no effort to create a labor force from Native Californians or other populations; in this case, the missions were established by those already laboring in the fields. And, unlike the Spanish missions, the Japanese missions were not representative of a dominant, conquering culture.

These were the missions of those who faced exclusion, discrimination, and a succession of laws that prevented citizenship and land ownership. These were the missions that followed their communities into the forced evacuation and confinement of World War II, safeguarding their congregants’ belongings and providing comfort for those inside relocation camps. These were the missions whose clergy were incarcerated along with their congregations. These were the missions who helped their flock return to West Coast communities after World War II, providing both shelter and guidance as they rebuilt lives.

The surviving Japanese mission sites are representative of those subjected to the largest forced evacuation and confinement in American history. They witnessed an often intense and painful struggle for civil liberties and citizenship in America, and were instrumental in the remarkable post-World War II recovery of Japanese Americans.

The Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1911-1912. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

In loving memory of Dr. E. A. Sturge

Physician, author, artist, and poet

Spiritual father to us

He loved the Japanese

For forty eight years onward from 1886 he dedicated his life to us

He established fourteen Japanese Presbyterian churches on the Pacific coast

~ Cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge, Japanese Cemetery, Colma, California

A cenotaph for Dr. E.A. Sturge in the Japanese Cemetery in Colma, California, notes "he gave us his very homes for our use in San Francisco and San Mateo." Sturge helped establish fourteen Japanese Presbyterian missions on the Pacific Coast.

Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D.

In San Francisco, the Christ United Presbyterian Church remembers E.A. Sturge each year on his birthday, referred to as “Sturge Sunday.” The mission was organized in San Francisco on May 16, 1885 as the First Japanese Presbyterian Church in San Francisco. It is the oldest Japanese Christian church in America.

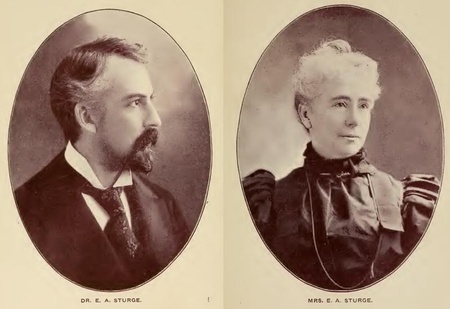

The year after its organization, Sturge was appointed by the national Presbyterian Church in 1886 to serve as Missionary of the Presbyterian Board to the Japanese in California, developing a statewide mission plan. His biography notes the Sturges “cheerfully taught classes of Japanese students who were anxious to learn the English language.” The couple is acknowledged as among the first to initiate mission efforts in the Japanese immigrant community in America.

(L-R) Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D. and his wife Mrs. C.H. Sturge. Mr. & Mrs. Sturge worked together on the Japanese mission efforts. (Images from "The Spirit of Japan," 1903)

Sturge was not an ordained minister, but held two doctorates: one as an M.D. and the other a Ph.D. He had traveled through Asia, working as a medical missionary in Siam (Thailand) and in China.

His time in Japan and with the Japanese community in America—originating in San Francisco—became the catalyst for his life’s work.

Henry Collin Minton, a chair at the San Francisco Theological Seminary from which graduated some of the first Japanese clergy, wrote “there is no more interesting missionary work on this continent than that which has been quietly but efficiently carried on all these years among the Japanese community” (in California).

In 1903, Sturge was honored by the publication of a book entitled, The Spirit of Japan, which included a selection of essays from colleagues and poetry by Sturge. It was published by the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Association as a surprise to recognize his “indefatigable zeal and painstaking kindness” and in “recognition for the years of earnest toil for the education and advancement of the Japanese.”

Ernest Adolphus Sturge and his wife with a group of mission assistants in northern California. (Image from "The Spirit of Japan," 1903)

One of The Spirit of Japan authors and editors, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa, submitted the volume to the Library of Congress, and it was entered officially by an Act of Congress in 1903.

Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa, the first clergy officially assigned to the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission as the first mission building opened in 1910. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

Rev. Inazawa was the first clergy at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1910. He and his wife, Kate Alice Goodman, were the first to live in the manse at Historic Wintersburg.

Inazawa writes of Sturge in The Spirit of Japan, “our beloved doctor has been my esteemed guardian, admirable teacher, confidential friend and elder brother…”

Another entry in the book is from Kisaburo Uyeno, His Imperial Japanese Majesty’s Consul in San Francisco, who noted by then Sturge had been living and working with the Japanese in America for twenty years.

“Since the opening of friendly relations with America, our people have been immigrating into this vast and wonderful country; and we are, today, nearly 20,000 strong. Many of our pioneers have encountered great difficulties and perplexities,” writes Uyeno. “Some have left behind them only their graves to narrate the tale of their careers, and all have come with the feeling that they were among ‘a strange people and under strange stars.’”

“But as we often see beautiful flowers blooming here and there among the briers and dried thorns, so these people have found on this stranger soil many kind hearts and great souls, who have shown them consideration and sympathy,” continues Uyeno. “For them we are greatly indebted for our prosperity on this coast and our friendship with the people here. Among these kindly Americans, Dr. Sturge stands very prominent.”

Portraits of those involved in California's Japanese mission effort, including Dr. E.A. Sturge (#1) and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission clergy, Reverend Joseph K. Inazawa (#5). (Image from "The Spirit of Japan," 1903)

Writing from Tokyo, Japan, Reverend Fumio Matsunaga says of Sturge that “though an American gentleman he resembles a Japanese knight of medieval age.” The admiration was mutual. Rev. Matusnaga had once presented Sturge with a copy of Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Dr. Inazo Nitobe, and recalled how Sturge was taken by the explanation of the Japanese code of honor.

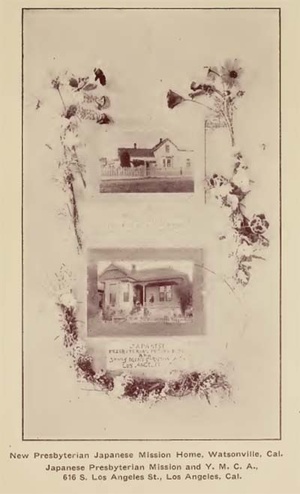

Two of the four California Japanese missions established as of 1903—one in Watsonville and the other in Los Angeles—are shown in "The Spirit of Japan," published one year before the Wintersburg Mission was founded in 1904. (Image from "The Spirit of Japan," 1903)

Published in 1903, The Spirit of Japan debuted one year before the founding of the Wintersburg Mission in 1904. At the time of publication, there were four Japanese Presbyterian missions in California: San Francisco, Watsonville, Salinas, and Los Angeles.

The next year, the Wintersburg Mission was founded with the help of Reverend Hisakichi Terasawa, who had traveled down from San Francisco—where Sturge was living—to work with Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries. He began holding services in a barn in Wintersburg Village.

Charles Furuta was among Rev. Terasawa’s first congregants, the first Japanese baptized Christian in Orange County, and became a trustee and elder of the Mission. His donation of land in Wintersburg Village fostered the Mission’s growth into an official church in 1930 and allowed for the second, larger church building in 1934. This places Charles Furuta among those pioneers who helped establish and support the Japanese mission trail in California.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on November 21, 2013.

© 2013 Mary Adams Urashima