Read Part 10 >>

Part Two: Dorothea Lange

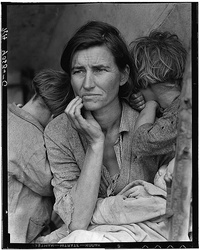

When Lange arrived at Manzanar in 1942 to take photos for the WRA, she was already famous for her 1930s documentary photos of the rural poor, part of her work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Her best known work, the bleakly beautiful Migrant Mother , a portrait of a seasonal farm worker and her two children, captured the weariness and desperation of rural America and became the iconic image of the Great Depression.

Lange's most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, taken in 1936 in Nipomo, CA; Lange was in accord with her mandate to show the plight of the rural poor.(Source: Library of Congress)

Lange was not instantly hailed as the champion of the downtrodden in the Japanese prison camps, however; that took several decades. While working for the FSA, the photographer had been in accord with that agency’s mission of explaining the ruinous effect of the Depression on Dust Bowl migrant farm workers and their need for government support. Her work for the WRA, the civilian agency created by President Roosevelt to oversee and carry out the forced removal and imprisonment of the Japanese, was different; Lange abhorred the agency’s mission. As a result, her relationship with the agency was contentious and oppressive.

The WRA hired Lange, along with photographers Clem Albers and Francis Stewart to document the massive relocation project and portray it as necessary and a humane act. (When the authorities told imprisoned Japanese that installing them far from the West Coast would protect them from rabid anti-Japanese sentiment, the often-heard retort was “If they are putting us here to protect us, why are the guns pointing toward us?”)

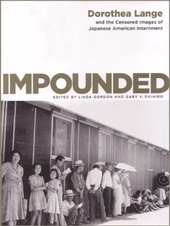

Although Adams was not on the WRA payroll when he visited Manzanar, he worked with the consent of that agency and project director Ralph Merritt. In the end, his work reflected the views of the WRA and Merritt more than Lange’s photographs. Plagued with misgivings over working for an agency whose mission she despised, Lange attempted to justify her work by showing the hardship and the suffering of the Japanese. The WRA in turn made her job difficult. In Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro’s 2006 book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of the Japanese American Internment , Gordon notes that Lange was “constantly followed,” “hounded, and refused access to what she was supposed to photograph,” while the WRA bureaucracy hassled her over phone call charges, mileage and gas receipts. Unlike her widely disseminated FSA work, Lange’s pictures were impounded during the war and afterward quietly placed in the National Archives.

As San Francisco Japanese assembled to be transported to Santa Anita racetrack, Lange (seated at rear, with camera) was there to document the event. (Source: Library of Congress)

More than 40 years later, Lange’s photos received a much different treatment in a 1987 National Museum of American History exhibition “A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the United States Constitution.” Although the curators chose not to identify photographers by name, they showcased Lange’s photographs of the exile and imprisonment of the Japanese Americans more than those by any other photographer. By then, her unambiguous critique of the mass roundup perfectly matched the prevailing view of the time, that the concentration camps were a gross miscarriage of justice.

Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro's book, Impounded, brought Lange's unpublished evacuation and prison camp photos to public attention.

In 2006, with the publication of Impounded , Gordon and Okihiro brought to the public’s attention many of the images that the government had suppressed. The differences between Lange’s and Adams’s views of Manzanar can be partly attributed to the timing of their visits. Lange documented the camp in June and July 1942, when conditions were harshest and inmates were shell-shocked over the sudden loss of their former lives and jobs. By the spring of 1944 Adams arrived at a physically different Manzanar, one shaped by the patient labor of inmates to include exquisitely cultivated gardens as well as a general store, functioning newspaper, furniture shop, clothing factory, canteen and hospital. The construction by inmates of a 14,000-square-foot high school auditorium was underway during his visits as well.

Gregarious by nature, Adams endeared himself to inmates and, as a good friend of Merritt’s, had no trouble gaining access to them. Patrick Nagatani’s mother remembers Adams square dancing with prisoners. Adams noted that when families in Manzanar knew that he would be taking their portrait they would dress up in their finest clothes and project a very different image than the stunned blankness conveyed by many of Lange’s newly rounded up and tagged subjects.

Lange’s involvement with the evacuation and imprisonment of the Japanese Americans was more personal and more troubled. She and her husband, University of California at Berkeley economist Paul Schuster Taylor, passionately objected to Executive Order 9066 and helplessly watched the relocation of a number of Japanese friends, some current or former students of Taylor’s. In contrast to Adams’s easy access to Manzanar, Lange “faced considerable harassment in trying to do the job,” writes Gordon. MPs followed Lange everywhere, refused her access to areas even though she had painstakingly acquired the proper clearance. She butted heads with WRA officials, who in one instance objected to her photograph of a Manzanar nurseryman sorting seedlings because a latticed roof cast shadows, evoking a prisoner behind bars. Lange felt a constant sense of guilt about working for the government responsible for the deeds she documented. Taylor self-censored his critical writings on the concentration camps for fear of the WRA firing Lange.

Lange butted heads with the WRA over photographs such as this, which the agency censored because the shadows resembled prison bars. (Photo: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Series 8: Manzanar Relocation Center)

In a 1994 essay on Lange and the WRA, historian Roger Daniels describes a point when Lange “was nearly overwhelmed by the quiet horror of what she had been photographing.” Lange’s photo assistant, Christina Gardner, described this moment, which came during an extended trip through Northern and central California to document the ousting of Japanese from their homes. Gardner recalled, “Dorothea was in some sort of paroxysm of fear…She realized that this was such an erosion of civil liberties, she had gotten so consumed by it and realized the import of it so heartily that it was something that I cannot explain to this day. I’ve never seen her that way before or since.”

Why did the WRA keep Lange employed given her obvious abhorrence for the government’s actions? Gordon speculates that the government was divided between the “army brass in charge” and lower-level administrators who were impressed by the reputation she made working for the FSA. They also may not have expected her photographs to be so critical.

From her earliest years, Lange had known what it felt like to be marginalized, an outside observer. Born in Hoboken, N.J., in 1895, she contracted polio at age seven, which left her with a slight limp. As her single mother worked, Lange attended school on the Lower East Side, seemingly the only gentile in a largely Jewish neighborhood. This experience, along with her mother’s accounts of working as a juvenile court investigator, and Lange’s experience at a private high school on the Upper West Side, exposed Lange to sharp polarities in ethnic, class and physical abilities that fostered a fierce independence and empathy for the downtrodden. She left home at age 22 for a trip around the world, but arrived in San Francisco and ended up staying there for the rest of her life.

Lange established herself as a portrait photographer of San Francisco society, and married a painter of Western scenes, Maynard Dixon. The harsh economic times of the Depression prompted Lange to take to the streets to photograph labor strikes, bread lines, unemployed and homeless urban dwellers. These photos marked a new direction for Lange and introduced her to Taylor, the progressive economics professor who became her second husband. Taylor had been documenting Mexican immigrant laborers since the late 1920s, learning Spanish and interviewing and photographing his subjects himself. When he saw a show of Lange’s photographs in an Oakland gallery, he immediately recognized a kindred spirit and wanted to meet her. A year later, in 1935, they had divorced their spouses and married each other.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto