Yes, there were Caucasians who visited the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona during World War II. Eleanor Roosevelt was one such visitor because our government thought its white barracks made it “the most attractive camp” of all the camps. And yet, although the truly noteworthy Caucasians who frequented Gila River were not of such import, they were in fact immensely more important than the First Lady. Too often these individuals are not only regrettably forgotten, but also are virtually nonexistent when recounting the tragic incarceration of Japanese Americans in this country over half a century ago.

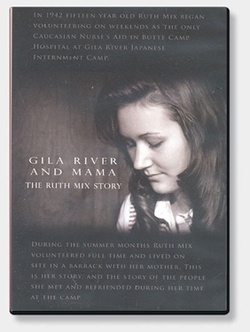

Claire’s mother and grandmother, Ruth and Frida Mix, respectively, are two such individuals whose courage and sacrifice should never be redacted from the Japanese American story. It is the duty of Japanese Americans to shed light on the many civilian Caucasians who voluntarily worked at the camps. That is exactly why this rare, firsthand account of a brave Caucasian volunteer (Gila River and Mama: The Ruth Mix Story) is a must-see for not only JANM supporters but for all Americans.

To a large degree, Caucasian volunteers like the documentarian’s mother and grandmother sacrificed much in the same way as did the Japanese Americans. The main difference was those like Ruth and Frida did it voluntarily. Of course, the Japanese Americans were profoundly more devastated by Executive Order 9066, but let us never take for granted what Caucasian volunteers sacrificed during that wartime hysteria: the chance to lead normal lives.

Ruth and her mother were frequently denied service in retail stores and restaurants; and in fact were ordered to leave the premises on many occasions. During Ruth’s four years of high school, she never made a single friend. Even if a few classmates sympathized with Ruth, their parents would forbid them from socializing with her. Consequently, Ruth was never invited over for dinners or parties. She was never asked to go to the movies. She never experienced prom or any other school dance.

On her way home from school, the other students would verbally and physically attack both Ruth and her brother because she was a “Jap lover.” When Ruth’s brother left school to join the service, she continued to fight off the other students. Ruth actually told Claire that she suffered more bruises and broken noses during high school than a prize fighter. One would think the high school’s principal or teachers would intervene but nobody ever did.

Despite basically being shunned and ostracized during the school week, Ruth steadfastly volunteered at Gila River on the weekends throughout the camp’s existence because she knew it was the right thing to do—even if that meant she had to endure despicable hatred wrought by ignorance in her community. Simply put, Ruth gave up any chance to live a normal teenage life because she stood up for what she believed.

“Miyoko” was Ruth’s first patient. After Ruth cared for her for four weeks, Miyoko died of an infection. Camp rules prevented her from seeing her kids in the weeks and days before she died. Miyoko’s infection was caused by her self-induced abortion; a decision Miyoko made because she was determined not to bring another child into the deplorable conditions of camp life. Ruth gave up a large portion of her youth to help those at Gila River, which Ruth referred to as a desert dungeon. Instead of enjoying a care-free teenage life, she was delivering stillborn babies in a desert because our government refused to supply American citizens of Japanese descent with proper medical services while they were wrongly imprisoned.

In fact, this is the very reason why Claire thinks her documentary (funded by a grant from the California State Library through the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program) has been so well received. She feels that a majority of the population are aware that, even though “[p]eople do not always like to look at their mistakes, we know we must, so that we will never repeat them.” Claire believes in this country, and is confident that the majority of its citizens realize they must educate themselves of this country’s darker periods, so that those distasteful memories will live on to remind us never to repeat certain events.

To be clear, though, Claire did not intend a political undertone to her documentary. Her two-pronged objectives were to educate and to share her mother’s story. With that said, however, she is cognizant that some audiences may make the connection with how Muslims in America have been treated over the past decade. Claire added that although the majority of her viewers walk away more enlightened about the Japanese American concentration camps through her mother’s story, she has also been referred to as “un-American,” among other colorful words, as well as the suggestion that she “was probably a Muslim lover.” Claire reflected how odd it was that she would be called “un-American” for standing up against the injustices suffered by her fellow American citizens. Moreover, she almost felt like she was standing in her mother’s shoes, when her mother was 15 and volunteering as a nurse’s aide at Gila River.

Claire is stunned every time she meets people her own age who basically know nothing about the camps. But even worse, she does run into people who actually have heard of the Japanese American incarceration but are quick to express how “pampered” the Japanese Americans were in the camps. Claire recounted attending a social gathering with her mother where somebody blurted that she wholeheartedly agreed with incarcerating the Japanese during World War II. Ruth, her mother, turned to the woman and asked, “Were you born a jackass, or did you have to work at it?”

But as mentioned before, Claire’s documentary has been well received; so the vast majority of her interactions with her audiences have been positive. Claire has met many World War II veterans, who fought in the Pacific, agree that the incarceration was a mistake. In addition, she has received hundreds of letters from Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in the camps, and from those who remembered both her mother and grandmother at Gila River.

Claire will forever be grateful for learning so much about her mother through these letters from people she has never met. She is also quick to point out that her extended family has grown since she has made so many friends. One Japanese American woman has given Claire the Japanese name of Akiko. Another man called up Claire and asked if she was the documentarian. He then gave only his first name. As he wept, he quietly asked Claire if he could simply share with her his story in the camps. He did not want to be in the documentary. He simply wanted to open up old wounds that were quite clear to Claire he had not opened much, if at all, since World War II. She ended up on the telephone with him for an hour. In the end, Claire will be the first to acknowledge that the people she has met and their stories will stay close to her heart for the rest of her life.

Claire not only intended to educate Caucasian and Japanese American audiences, but also those directly involved with her documentary. She felt it was important for the actors on set to receive an education as well, especially because she was working mostly with teenagers and young children. She “allowed a question-and-answer time before and after [they] filmed each day to make certain that each person involved with this project knew what they were doing and why.”

In addition to the actors in the documentary, Claire believes her film reaches both Japanese Americans and Caucasian audiences, but especially Caucasians because the story is conveyed from a Caucasian prospective who saw firsthand the deplorable conditions under which the Japanese Americans were forced to live. Claire intended to educate the Caucasian audience to not take on the mob mentality of “if you look like the enemy, you must be the enemy”; that there is another option besides status quo, with her mother and grandmother as shining examples.

Regarding her Japanese American audience, Claire intended to educate the younger generations of today that not every Caucasian agreed with Executive Order 9066, which is what some of the young Japanese Americans growing up in the aftermath of World War II thought was true. One particular woman comes to mind. Claire received an email from a woman who was incarcerated at Gila River as a child. At the time this woman believed that every Caucasian person hated her, and sadly this thinking stayed with her until she saw Claire’s documentary. Afterward, she felt a great weight lifted from her shoulders after these many decades. The woman told Claire that she has never discussed her incarceration with her children or grandchildren. But that once she saw the documentary and was able to open up to her family about her experiences during World War II, the woman felt like her family was meeting her for the first time. These are some of the results Claire was hoping for in regards to educating people with her documentary.

Ultimately, however, this documentary may not be about American history or about the documentarian’s desire to educate the public, especially the younger generations. At the heart of this documentary process is the deeper connection reached between a loving mother and daughter: a lifelong journey culminating in this cathartic storytelling.

Claire’s lifelong quest to learn more about her mother’s closely guarded experiences during World War II began at age 13 when her mother raised her hand and told the lecturer George Takei that she had volunteered at Gila River. After the lecture, the actor and Claire’s mother talked privately. That was Claire’s first exposure to the Japanese American incarceration. Claire was not able to get too much out of her mother until the tragic events of September 11, 2001. At the time, her mother expressed to Claire her concern about the Muslim community in America, that they might suffer what the Japanese American community suffered during World War II.

Since that tragic day in 2001, Claire’s mother became much more open to answering questions about Gila River including the people she grew to love there. For Claire it was clear: she needed this documentary project to learn a side of her mother that she never truly knew. After interviewing Ruth for this documentary, so many questions about her mother’s personality were cleared up for Claire. For example, she finally realized why her mother disliked a particular religion so much and it was because her religious classmates were the ones who verbally and physically attacked her after school. Not only was Claire grateful to her mother for sharing her experiences, but her mother was also grateful to Claire for making her talk about it.

Ruth Mix passed away seven months after the interview, but Claire has been honoring her mother ever since by carrying out her mother’s wish that Claire “teach the rest of the world about” Gila River and how we cannot make the same mistake twice.

Upcoming project

Claire Mix has recently completed a follow-up project: a young adult novelization of her mother’s story. The novel contains much more detail of Ruth’s experiences at Gila River. Claire wrote it as if her mother were telling the story in real time. With this follow-up project, Claire was intent on giving it a crossover appeal so that adults could enjoy the reading as well. Many of the stories her mother shared with her could not be put in the film: stories about her social life at Gila River with all the friends she made and the patients she cared for at the hospital; emotions as expressed in a diary Claire’s mother left for her; relevant photographs; not to mention her mother’s stories of smuggling in basic amenities for the Japanese Americans such as soap, powder, deodorant, and even food. The book is entitled, The Girl With Hair Like The Sun, which was her mother’s nickname at Gila River because of her bright red hair.

Claire’s ultimate goal is to have the book in every elementary school library in America. For more information about the book, please visit http://www.facebook.com/TheGirlWithHairLikeTheSun.

For more information about the documentary, please visit http://www.gilariverandmama.com.

----------------

Please join us on August 20, 2011, at 2:00 P.M., as The Japanese American National Museum hosts a screening of the documentary, Gila River and Mama: The Ruth Mix Story , followed by a Q&A with Ruth’s daughter, Claire Mix. Additionally, if you are unable to make the screening, the documentary can be purchased online at http://janmstore.com/40110.html.

© 2011 Edward Yoshida