Read Part 19 >>

COMMUNITY EVENTS AND CELEBRATIONS

In the early years, one of the most important and controversial events was tenchosetsu, the celebration of the Emperor Meiji’s birthday on November 3. Though at first the plantations in Hawaii did not recognize it a holiday, all work stopped as the Issei workers took the day to celebrate with food, music, and dance. “Jara-jara, jan-jan, chan-chan.” Went the shamisens (three stringed instruments) as the people ate their food and danced into the night.1 By the mid-1890s the planters were forced to officially acknowledge in each worker’s contracts the right of Japanese laborers to celebrate tenchosetsu.

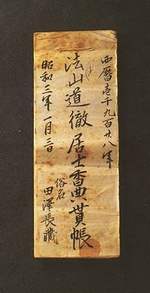

Record of monetary funeral offerings kept by the family of Chozo Tazawa, 1928. (Gift of Haruno Tazawa, Japanese American National Museum [97.90.1])

Even more important than the celebration of birthdays were the proper observances of death. A funeral in the Japanese immigrant community was an affirmation of family and community ties. There was a strong sense of obligation to attend the funeral of family members, relatives, and acquaintances and large gatherings were common. The attendance at a funeral indicated the wealth and status of the deceased in the community. Certain to be present was the local photographer who, at the end of the funeral service, captured the mourners in a panoramic shot. These photos were sent to Japan to console families back home and assure them that even in death the deceased was paid proper respect.

At the funeral, it was customary for friends and relatives of the deceased to give koden (a monetary funeral gift) to the family of the deceased in order to help pay for the cost of the funeral. Since many if the Issei did not have relatives present, the community came to the aid of the mourning family.

“I feel so ashamed. to think that I had received so much help from friends to conduct a funeral service for my husband,” lamented Haruno Tazawa. “I can never hold up my head again if I’m able to afford a few luxuries now.” Chozo Tazawa. A luna (foremen) at the Ewa Plantation in Hawaii, died January 3, 1928 at age fifty-four. He left a wife and four children, ranging from two to nine years old. Although he was earning $85.00 a month at the time of his death, Chozo’s gambling habit had left Haruno with only 35 cents in the family coffer. “With 35 cents, I couldn’t even buy senko (incense) for the hotoke-san (the departed soul),” remembered Haruno. “All my friends dashi dashi (chipped in) for the funeral. That’s the reason why I can never forget that day. Even now, I cannot indulge in luxury even if I have enough from pension money. I can’t walk proudly down the street like others because of that.”2

One of the most joyous occasions for the children was New Year’s day. In preparation for New Year’s day, families paid old debts and cleaned up misunderstandings to start the new year with a clean slate. Some families spent weeks in preparing special feasts for guests who came to east. drink, and pay their respect and good wishes for the coming year.

Special New Year’s food

The tongue reminds the heart

Yearningly of home3

Battledore with shuttlecock (Gift of the Yogi Family [89.32.1 / 89.32.1A]), Poem cards (hyaku-nin isshu) (Gift of Tamateru and Sunao Kodama, Japanese American National Museum [90.21.1])

The rhythmic sound of mochi-tsuki (preparation of rice-cake) filled the morning air as men with wooden mallets pounded the sticky rice placed in a pestle. Greetings of “omedeto” (congratulations) were exchanged as the family sat down to drink toso, a ceremonial drink mixed with sake (rice wine), sweetened liquor, cinnamon, and other spices. After each member, in order of seniority, drank a thimbleful, the family was ready to eat o-zoni. rice-cake boiled in soup. Girls received presents of battledores and shuttlecocks and the boys joined in to play hyaku-nin isshu (poem cards).

The hyakun-nin isshu set is composed of a hundred poems of thirty-one syllables each, written by poets of classic fame. While a reader recites out loud the poem written on each card, the players on two opposing teams compete for the card with the closing lines for the poem.

“Imagine a boatman on a passage to Yura with helm all unstrung”

(recites the reader)“Such is my love which drifts on and on only heaven knows whither.”

(reads the player, completing the passage of the poem)

While sipping sake, enjoying the traditional feast, watching the children play, and listening to popular songs like “Okesa Bushi” accompanied by the shamisen (three-stringed instrument). Thoughts of Japan filled the Issei with nostalgia. Even after the passage of years, many families still prepared a special New Year’s feast and without fail ate o-zoni on New Year’s morning. But the karuta card game eventually found a resting place in the closet as fewer children could participate, unable to recite or read the hundred poems, much to the dissatisfaction of their parents.

Preparation of rice-cake for New Year's day, 1915. (Gift of Sue S. Ando, Japanese American National Museum [93.34.1])

O-bon, the Festival of Lanterns, was one of the highlights of the summer months when the Issei acknowledged gratitude to ancestors and welcomed home the spirits of the dead. Among the second generation much of its meaning gave way to the gaiety of the event when paper lanterns lit the streets and women and children wearing colorful yukata (summer Kimono) danced to the accompaniment of musicians playing shamisen (three-stringed instrument) and drums, and women singing “Tokyo Ondo” and “Kushimoto Bushi.”

Kiku Miyazaki clearly remembered Seattle’s o-bon with six hundred people, grouped according to prefectures, dancing in a circle around the yagura (platform) where the musicians and singers performed. “Japanese lanterns hung at all stores, and both sides of the street were filled with spectators including many white people. It was just a ‘Japan Night.’”4 The dancing differed depending on the prefecture. Seichin Nagayama, an Okinawan, explained, “In Iwakuni bon odori [dancing], they just beat the drums. In Okinawan bon odori, the dancers turn around and around and the dancing is varied.”5

Summer was also the time for community picnics. Masako Osada described July in Tacoma before World War II when Buddhist Church members, prefectural clubs and various occupational groups held picnics and went to Dash Point, Brown Point and Fox Island.” Families packed “a typical Japanese picnic lunch with sushi, yokan (sweet bean cake), boiled eggs.... Those who liked fishing caught rock-cod and roasted them immediately.” Squid and butterclams were made into sashimi. To the tune of a Japanese folk song, Masako and others would sing:

A nice place, Tacoma! Come over once

Mushrooms on the hill, octopus in the sea.6

Picnic

Looking up at the sky

I feel young again.

With my children and grandchildren

What a joy,

The picnic.7

Traditional sports such as sumo (wrestling), kendo (fencing), and judo continued to hold their popularity among the Issei. Baseball became the favored Western sport in both Hawaii and on the Mainland. In 1902, Reverend Okumura of Hawaii organized the first Japanese baseball team among students at the boarding school. Within a few years, other teams were organized, competing against teams from other plantations or other ethnic groups, On the Mainland, baseball teams challenged teams in other locales, traveling up and down the west coast.

Nisei baseball team uniform with shoes and mit of Fred Kishi, Livingston, California, ca. 1937. (Gift of Fred Kishi [91.97.1A / 91.97.1B / 91.97.3 / 91.97.4]), Japanese fencing uniform and equipment of John Kobashi, Date unknown (Gift of the John Kobashi Family [91.89.1-6/91.11]), Kendo sticks (gift of Norio Mitsuoka [91.11.16]), baseball bat of George Omachi (Gift of George Hats Omachi, Japanese American National Museum [91.50.3])

Notes:

1. Seichin Nagayama, Uchinanchu, p. 472.

2. Haruno Tazawa, January 15, 1984, interviewed by Barbara Kawakami.

3. Hideko, Ito, Issei, p. 739.

4. Kiku Miyazaki, Ito, Issei, p. 807.

5. Seichin Nagayama interview, Uchinanchu, p. 472.

6. Masako Osada, Ito, Issei, pp. 804-805.

7. Chiye Nakagawa, Los Angeles, 1991.

* Issei Pioneers: Hawai‘i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 is the catalogue accompanying the National Museum’s inaugural exhibition. Using artifacts from the National Museum’s collection to tell the story of the courageous “Issei Pioneers,” the catalogue focuses on the early immigration and settlement years. To order the catalogue >>

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum