Part 2 >>

Amano confirmed that military personnel did more than mistreat prisoners for entertainment; they gathered intelligence in concert with the FBI. Amano revealed in his statements that his highly suspect activities and defiant attitude made him a target. While captive, the Americans identified Amano only by the number on his prison-issued clothes. “My number was 203, a bad omen. Everyone knew about 203, a fort Japan fought for in Russia.”

The significance of number 203 derived from The Battle of 203-Meter Hill and the Siege of Port Arthur in 1904 during the Russo-Japanese War. The battle was noteworthy both for the large number of Japanese casualties and for the tenacity and bravery exhibited by the Japanese soldiers. Hearing the guards call him by number, Amano expected the worst:

I thought of a spy movie, where the guy gets shot. I thought of that and shuddered. My former employees came around and started asking if I was going to be executed (hand gesture). It was a terrible suggestion. Furthermore, they asked if I wanted to leave any word to the others. I expected to die. The soldiers walked quickly. So I looked back at my life – kind of a selfish life. I never took orders from anyone and I did everything I wanted to do. That life was over now. When it’s my time to die, it’s my time.

Two soldiers escorted Amano to a tent for questioning. He described the interrogators as a sergeant, a Nisei translator, and an MP named “Cibure” (Sibbly?) who seemed to be in charge. After Officer Sibbly asked a number of general questions, guards escorted Amano back to his quarters, much to the relief of his employees.

Another interrogation took place a few days later. Amano paraphrased Officer Sibbly’s questions and his answers:

‘You must have known when the war was going to start. What was your position in Japan?’ ‘Why should I know? I didn’t know anything about it. I was just a merchant.’ ‘We have evidence. Why did you go to the bank the day before to withdraw money?’ That’s true. Friday morning, I went to Panama’s National City Bank and saw the manager. I asked the manager to give me my money in cash. I wrapped the money in paper. I told the manager I was going to leave the money in a safe deposit box. I rented the box for one year and I put money in it. But that night, I was thinking, that was still an American bank. If something happened, the money wasn’t safe for me. I made a paper wrapper and the next day, I went back to the bank and switched fake money for the real cash. I’m sure they were surprised when the war started and they opened the box and discovered the money was fake. Sibbly kept asking, ‘Where was the money? How did you spend it? Why did you take it out?’ I divided it among creditors. I paid the bills. Another question. ‘We started searching your house. We couldn’t find anything suspicious.’ It was so stupid.

Amano clamed the FBI questioned him only once, describing the agent as young, refined and polite. He asked about Amano’s family and questioned whether they could subsist without funds regularly wired to Japan. The military inquiries, however, continued.

Amano described an angry Officer Sibbly presiding over a sixth interrogation session:

‘A month before the war started, you hid six airplanes at your ranch in Chile. We have evidence from a military harbor report. They sent six planes to your ranch. We know everything so you better start saying what you know.’ I was just so shocked to hear that kind of question. By the same token, I was disdainful of the American military intelligence department. I was disappointed with it because I’d respected it before. So I was trying to joke and make Sibbly laugh so he’d be easy on me. I said, ‘Mr. Sibbly, don’t you think six planes is overdoing it? I only know of one.’ ‘Alright, if you know about one plane, you better describe what type of plane is on your ranch and explain its purpose.’ He was excited and his voice got louder. I was determined to try to make him laugh. ‘That plane is about two meters long and cost $1.25. My son was there and I brought the plane to him. I don’t remember bringing any other planes to him.’ Instead, Sibbly’s face got red and he started shaking and shouted, ‘Shut up!’ He thought I was insulting him. After that, all the enemy’s hatred was focused on me.

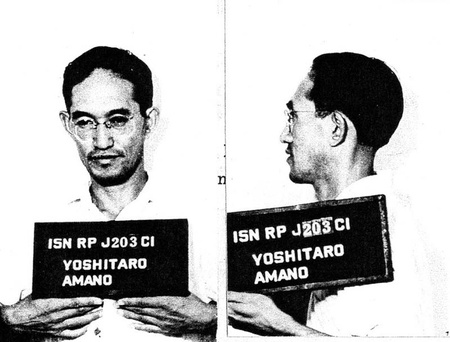

Other prisoners besides Amano were allowed to receive mail and occasional visitors. Amano described especially difficult or dirty work assignments reserved for him, denial of medical treatment and special orders issued to a sentry to shoot if he came within ten feet of the gate. Because “they thought all of us looked alike,” soldiers photographed him many times. “I’m sure they’d use this image in the movie theater with the caption, ‘This is the spy we caught in Panama.’ I thought it was a great honor!” Amano did not mention if other prisoners were subjected to interrogation.

In the next few chapters of Waga Toraware No Ki, Amano ridiculed roll call and convoluted mess hall procedures as prisoners schemed to get extra meals. He also detailed efforts to smuggle newspapers, assisted by black Panamanian camp workers, and evenings passed following the progress of the war along with hours playing board games using hand-carved game pieces.

After several months, Amano recalled, “an incident gave us a jolt – all the Italians were freed. At the next camp, 230 Italians were held but in March, the Americans started releasing them. Ten one day, fifteen the next. Some people were so excited that they were walking on air.” All the Japanese remained in camp joined by more recent arrivals of Japanese prisoners from elsewhere in Latin America.

Concerned about the capacity of Panama’s interment facilities, military officials suggested that the enemy aliens be sent to America. The United States paid Panama for the costs of internment and shipment of Japanese Latin American prisoners. The Panamanian prisoners became part of the first shipment of hostages sent first to American internment camps before repatriation in Japan. These captives and other Axis prisoners, primarily from Peru, arrived in New Orleans on April 8, 1942.

Amano claimed he had expected transfer to the United States. “I’d already heard that news in mid-January from the Spanish consulate. He came four or five times to camp but I never got a chance to see him even once.” Still, rumors spread quickly among the inmates who anticipated better conditions in American prisons.

Amano described the dramatic events that preceded the transfer. On March 29, 1942, soldiers strip-searched the inmates and inspected their tents, slashing pillows, ripping duffle bags apart, and checking tent poles. “Some even cut bars of soap in half. We lost our diaries – anything with words was destroyed,” Amano recalled.

Awakened by soldiers at five o’clock in the morning on April 2, the prisoners were marched to a train waiting at a nearby station. He noticed that German and Italian prisoners were already on board but worried about not seeing the Japanese women and children. However, Amano was later relieved to learn they had been quartered at a yacht club near an immigration building. In addition to the two hundred Japanese, the facility held about forty-five German women and children. Amano, usually careful to note precise numbers, did not mention a specific number of imprisoned German or Italian adult males.

The prisoners speculated that, once aboard a ship, a Pacific route offered hope for rescue by a Japanese vessel but worried about German submarines patrolling the Atlantic Ocean. Amano described boarding the Florida, a ship on which he had once been a paying passenger. Again, he noticed that the Germans and Italians were already on board. After a number of prisoners fell ill from a carbon monoxide-filled hold, they were allowed on deck to revive under the surveillance of soldiers with bayonets stationed at ten-foot intervals.

The ship headed out of Cristóbal Harbor to Limón Bay where “we picked up another fifty Germans, all caught by the Costa Rican government. I remembered so many of their faces from San José and [we] nodded at each other in recognition, smiling sadly.” The ship took a zig-zag route to evade a torpedo attack.

Three days into the trip, worries about submarines were justified. Someone spotted a periscope which was quickly followed by the sound of gunfire. Amano reported that the ship evaded two more attacks before entering Puerto Barrios, Guatemala’s harbor, to pick up up twenty Germans captured by the Guatemalan government. According to Amano, the Florida headed for the gulf on April 6 and passed through the Mississippi delta on April 8. Nine hours later, the ship dropped anchor in New Orleans. Two military motorboats circled the ship all night.

© 2010 Esther Newman