Right at the center of Chugoku lays the prefecture of Hiroshima, one of the most fascinating, mountainous regions of Japan. The many rivers that cross it have created bountiful plains near the coast. The lovely breezes of the Seto Inland Sea, sheltered within Honshu and Shikoku tame the summer, and help Chugoku enjoy a gentle climate. The locale is home to several important towns; but the village of Umaki goes almost unnoticed. Now small, it was much more so in 1904, when Japan suddenly surged as an international power…and when Saichi Yamashita made it to life. Part of the home, where he was born still exists. And so do some of his relatives in that remarkable Yamashita family.

The genes from ancient land-owners on his father’s side and gentry on his mother’s, the local Tani clan, melded into an atypical combination. And Saichi was born chonan—first child and family heir. In the late Meiji era, Japanese families were encouraged—even compelled—to impart upon their children, particularly the chonan, the best education. So Saichi, quite a handsome boy, made it all the way to kōkō, high school. But those benefits had an onerous tag. At age 20, like most other males in his generation, Saichi had to serve a couple of years in the military, under the Conscription Act of 1873. And that left him a “marked man.”

Ueharada-san, Saichi’s brother-in-law, had been to America and had worked in Northern California; his wonderful tales about Beikoku (the United States) nearly singed Saichi’s brain; he craved to go see. But passports were only for the wealthy and powerful. And the infamous U.S. Immigration laws of 1924 excluded Asian commoners from migrating to America.

Yet, the alternative was so clear: befriend deck hands from one of the cargo ships going to America and convince them to help Saichi and two of his buddies stow away. He found some sailors who agreed to the scheme. That meant traveling with only what fitted inside a strong furoshiki (a wrapping cloth). The trip to San Pedro took three hideous months. The complicit mariners fed the trio daily and protected them from discovery. Upon arrival without a chance for good-bye and thank-you, and with only the lights of the mainland a mile away to guide them, the trio jumped ship. Three splashes broke the midnight silence; nobody heard them…or cared.

How they made it to shore not ending in a shark’s belly or dead from over exposure will be forever unknown. All Saichi told about that night is that he swam interminably, somehow balancing on his head the precious furoshiki with his possessions, and the address of a contact in Los Angeles. The trio landed undetected; dawn was just breaking.

Next, they started on the road to somewhere. A Japanese hauler noticed the wretched group, stopped his truck and offered them a ride. In 1927, you could still give a lift to a pedestrian without the fear of being assaulted. The scene might have gone like this:

– Doko-e iku no? (Where are you going?)

– Rosanzerusu…(Los Angeles…)

– Mah! you guys sure were pointed the wrong way. Torakku ni notte. Sa, ikou! (Hop up in the truck. Let’s go!)

He took them to “J-Town,” where they split. Saichi got in touch with the Totanis, friends of the Yamashita clan in Japan, and his contacts in Los Angeles. And from then, life in America began perking up. He worked in the Los Angeles farms, in Baldwin Park and other agricultural areas of the San Gabriel Valley. He became “Frank”—and a gardener—sometime around then.

Though he was an excellent worker, the going was tough. As he expanded his contacts, he met his future wife, Kazue Sogioka, who, initially, couldn’t care much for him. Ten years his junior, bright and ambitious, she wanted college and a career. But that was a costly proposition. In the end, they married in September of 1933, and had several children.

Through hard work, saving, and tempting fate, the Yamashitas became independent and established a Florist and Nursery Shop in the better part of Arcadia. Their business flourished; and they could have become millionaires had American history been a tinge less capricious. Frank became very active in the local Gardeners’ Association.

Then Pearl Harbor happened. One night, a group of government agents came to the Yamashita home. Frank was outside the house. In a few words he was ordered to surrender and go with them immediately. He asked for a chance to go inside and get his coat, but permission was denied. His forced conscription into the Japanese Imperial Army many years ago, and his leadership in the community had made him a prime suspect of mayhem, espionage, and terrorism. He was jailed for a while, and then moved to Montana. But finally, he was allowed to join his family at Heart Mountain, perhaps the most depressing of all the ten dismal concentration camps.

Many of the incarcerated Japanese were seething at the treatment they had received at the hands of the government. They couldn’t understand how American citizens could be illegally imprisoned just for being of Japanese descent. The confusing “loyalty questionnaire” imposed on the detainees made things even more blurry. Frank was among the unhappy; so, the family was moved to the Segregation Camp at Tule Lake. He seriously considered repatriation to Japan. Kazue didn’t know anybody in Japan, nor wanted their American-born children to be dumped there during those unfortunate years. The issue finally came to a head.

“If you want to return to Japan, you go alone; we stay,” said Kazue.

That settled the question for good.

Fortunately internment came to an end, and the people were let out—some forced out of the camps. Most detainees had nowhere to go, except back to the prejudices and hatred still lavishly vented upon them.

What do you do then with no home, all your former wealth gone, and so many mouths to feed? Where do you go when folks in your previous habitat would rather see you at the moon than nearby? Frank came back to start again at the San Gabriel Valley. Initially, Rev. Yokoi, pastor of the Japanese Methodist Church, in El Monte, hosted the family.1 For a while they lived in an empty classroom behind the church. In gratitude, the entire family joined Rev. Yokoi’s congregation.

Later, the Yamashitas moved to an old empty house in their brother-in-law’s ranch at La Puente—near Francisquito, Sunset and Fairgrove. Frank managed to get an old model “A” Ford truck and began gardening again. He created a circle of loyal customers enchanted with his gardening skills. He dreamed to open a nursery again, but that goal was never realized. In time, he acquired a large property in El Monte, and soon he expanded into landscaping. Again, Arcadia, Monrovia and the Foothills provided a splendid environment for his talents.

He read voraciously. Perhaps that’s how he learned landscaping. He detested manicured lawns accented with encapsulated junipers looking like soccer balls hanging from a pole. To him each tree deserved just encouragement to maintain its natural beauty. He began finding clients who wanted a “Japanese garden” on their property. They would ask him for a sketch or a plan but he never produced even one. He just smiled, told clients that everything was in his head, and bade their full trust. When he won it, he just went to work. He had a mysterious feeling for soils, mini-climates, and the entire natural and social geography. He knew where plant, bridge, rock, pond and toro (lantern), each of his own choice or creation, could show their best. Wherever he built, he did it in the most exquisite tariki2 form. Frank the landscaper became the landscape.

His skills blossomed and he created the most beautiful Japanese gardens in Arcadia and Monrovia—not one ever a look-alike. His prized jewel was the garden he built on a very large property designed like a fan, in The Foothills. It was a superb challenge that ended with fantastic results. He cultivated and raised the Japanese kuromatsu—the traditional “Black Pine” that became Frank Yamashita’s passion, and he became the top West Coast expert in that art, referred to as “Mr. Black Pine.” He also left a strong imprint of his talent at Descanso Gardens—the beauty of his toro.

An older hakujin friend, a large man with a huge handlebar mustachio, who might have picked up the craft in Japan, taught Frank how to cast his own toro-stone lanterns. Whatever its form, every one of Frank’s toro was so polished that it looked as if just chiseled out of a rock. The more he learned the more he shared his skills with his gardener friends, who adopted him as their Mentor. And to his clients, Frank became a dear friend, and a genius whose wisdom they deeply enjoyed.

He obtained his American citizenship shortly after Congress passed the controversial McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952. That law, while ending the denial of citizenship to Asian immigrants, still restricted and limited Japanese immigration to America. In 1959, Frank went back to Japan to visit his parents. His father had died broken-hearted without a chance to see his chonan again for more than 32 years. The reunion with his mother was emotionally overwhelming. She died soon thereafter.

Thanks to his American citizenship, Frank could now go back to Japan as often as he wished, and he managed to exercise that privilege, often taking the family with him, and bringing back new saplings of Japanese kuromatsu, the traditional Japanese garden tools that he preferred over those made in the United States, and some koi, the pricey Japanese carps.

Frank was always deeply involved with the East San Gabriel Valley Gardeners’ Association3 of which he was its first President, and with the Edgewood Landscape Gardeners Association. He was a tireless participant in many of the Center’s internal and external activities, and a top member of the shigin4and the haiku5 poetry groups. His wife Kazue was also very active in the Center, particularly with the “Gabrites” and the “Old Timers”—the Leisure Club. In 1966, when the Center moved to its current location, Frank landscaped by himself, the front of the property. Twelve kuromatsu, one akamatsu (red pine) and a group of junipers from his own collection, together with some gigantic boulders were chosen as the accents for the plot. Eight years later, when he became 70, he added the SEVENTY cypresses that surround the perimeter of the property…one tree for each year of his life. I believe he also planted the clumps of Nandina6 around the gym, and the other vegetation in the parking area planters. He also donated several of his lanterns—one dated 1951. At some time, he also provided three of his beautiful black pines to the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center in Little Tokyo.

As a regular member, Frank often attended the Leisure Club meets, making many new friends there, and often bringing fruits and other vegetables from his personal garden. For one of his friends, Mrs. Kyoko Okada, he grafted a lemon tree which would provide citrus fruit over the entire year: tangelos, tangerines, and Mexican limes. The tree is still alive, though years of service have taken their toll on it.

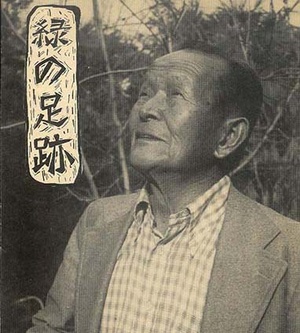

Both Frank and Kazue aged very gracefully. Even in his seventies Frank cut a very impressive figure. His strong, sinewy hands irradiated magnificent strength, deftness and creativity. His fingers projected the tenderness he always showed to his plants. He kept caring for his priceless landscapes until his late years. The conifers had to be trimmed yearly every May. When he no longer could climb a ladder to clip and trim, he pointed with his cane to what his assistants had to cull or remove. In his eighties, he was still planting and babying kuromatsu saplings with unrelenting passion. One has to realize that before a tree can be set on a garden, it may take between twenty and thirty years of nursing.

What are you doing, Frank…?

“How and when do you think you’ll be able to use those trees?” Kazue would say in total frustration, when he started a new collection of saplings. But he just kept at the task totally unconcerned about uncertain morrows. Kazue died in 1991. Curiously enough, he survived her ten years, same as the age difference that separated them.

Frank’s enormous contributions to beautify Southern California were not duly acknowledged during his life. He received an Agricultural Medal from his Mother Country; and was also honored as a Pioneer at one Nisei Week in Little Tokyo. However, he was never accorded the major awards he deserved as an exemplary trail blazer, top artist, teacher, and foremost contributor to the beautification of Southern California. Being truly modest and unassuming, casual appreciation of his great talents was enough for him. One of his haiku expresses that attitude with extreme clarity:

Utsukushiku (As the beautiful dew drop)

Kiete hatte un ya (May my life one day)

Tsu yu no tama (Simply fade away)7

Indeed, all his fellow gardeners, his clients and their children still regard him as a great influence in their lives, and also wish he would have been showered with great distinction. Frank died in June, 2001. By then, many of his contemporaries had already passed away. A very poignant haiku for the 3rd Reunion of Pre-war survivors reveals his readiness to follow them:

Tomo no uku (Friends are gone)

Michi ware mo yuku (Traveling this road)

Aki no kure (So shall I at Autumn’s end)8

For me, Frank represents the vibrant Yamato spirit blended with the Japanese-American creativity that has so enriched our country. In the Nihon legend, the sacred kuromatsu are born to live hundreds of years, and finally become heavenly green dragons at their lives’ end. Frank Yamashita left us an enormous gift, a legendary reality we’ll be proud to pass on to future generations in memory of his genius.

My deep gratitude goes to Aileen Tanaka and Susan Arii, Frank’s daughters, and Larry Arii, his son-in-law for their lovely memories and archival materials about him. Thanks also to Kim Hatakeyama, Past President, ESGVJCC; to Beans Sogioka, Frank‘s brother-in-law, Mmes. Kyoko Okada and May Sakoda, and to Bacon Sakatani for their additional information and valuable materials. I’ve also consulted several publications, including The Kashu Mainichi; Naomi Hirahara’s Green Makers, published by the Southern California Gardener’s Association; several books on the History of the Issei; our own Center’s “50th Anniversary Report,” and the “Pre-War San Gabriel Valley Reunion” annuals, published by Bacon Sakatani. Thanks especially to my wife Reiko for her ideas, and for her help in deciphering a small pamphlet (undated)—in Japanese—about Frank’s remarkable life.

Notes:

1. The church is now known as Sage Methodist Church.

2. Tariki is an Amidist Buddhism concept. Its essence is the spontaneous, wondrous force that gives us the will to act, to do what man can do and then wait for heaven’s will. Itsuki Hiroyuki, TARIKI, (2001), Tokyo: Kodansha.

In the field of aesthetics, it’s the moment when the creator becomes the creation and vice versa.

3. By 1951, the Association had become the East San Gabriel Valley Japanese Community Center, in which the gardeners maintained their own group.

4. Shigin is a form of Japanese poetry, usually chanted singly or in groups.

5. Haiku perhaps the shortest poem form in the world (5-7-5 syllables)combining the canons of hokku and haika versification, is often associated with its foremost interpreter, Matsuo Basho. Perception, breadth and depth of feeling, and graceful form are the distinguishing characteristics of the most successful haiku.

6. Also known as heavenly or sacred bamboo, Nandina-aka-nanten: South Heaven. Japanese lore attributes many lucky and positive attributes to this beautiful plant.

7. From the Pre-War San Gabriel Valley Reunion III annual, with calligraphy by Mrs. Kyoko Okada and translation by Mrs. May Sakoda.

8. Ibid. Frank selected the name Issan as his poet’s signature.

© 2010 Edward Moreno