Okubo was interned in 1942 in the Central Utah Relocation Center in Topaz a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor. During that time she created drawings depicting the life of the Japanese Americans in the camp. When she returned home she added text to this collection. In 1946 she published it and named it Citizen 13660.

When I first encountered this book I did not pay much attention to it. I saw it in a comic book store several weeks before I attended a seminar and learned about the context and the meaning of it. Nevertheless when I saw it in this comic book store, I had the feeling that it was out of place.

When I started the course and our instructor presented it to us, I recognized it at once and decided to take a closer look at it. Even though I do not argue about the fact that it is a graphic novel, I do think that this is much more than just an illustrated story.

Miné Okubo was able to depict the most intimate situations in the internment camp in a very subtle but still very emotional way. In addition to that she was able to offer a perspective from the Japanese American point of view, which was something that photographers like Ansel Adams or Dorothea Lange could not do.

While I was reading the graphic novel, I constantly wondered how some of these images could escape censorship. Even though they do not show blood or obviously suffering people, a lot of these images have a bitter tone to them. I think that the real impact of what is happening is not just evoked by the images themselves, but through their correspondence to the text, that was added after she left the internment camp.

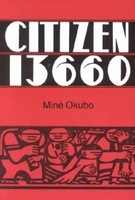

An example would be the image of a camp scene.

There are three huts in the background and the entries of four more on the left hand side. You can also see a lot of people in front of the huts, and Miné and the back of another person on the right hand side. In the background of the image you can see a sign on a remote hill, which says “Enjoy Acme Beer.” The picture itself does not give us any clue why these words are written on top of a hill. It looks like an unimportant note on the paper. The scene in itself does not tell us much about the camp life. But then we do have the words underneath the image:

“A huge sign, “Enjoy Acme Beer”, stood out like a beacon on a near-by hill. The sign was clearly visible from every section of the camp and was quite a joke to the thirsty evacuees, especially on the warm days.”

These two sentences give the image a different, much deeper meaning. Now we know why she tried to show this sign in her picture. But this is not all. If we study the picture again, knowing the context, the first thing which came to my mind was Miné’s face. She looks tired, worn out and has shadows under her eyes. Maybe she is not only tired, but thirsty as well. The sign is humiliating for the people who are suffering in this desert like place. They have to endure thirst and heat while constantly having to look at the advertising promoting a nice and probably cool beer.

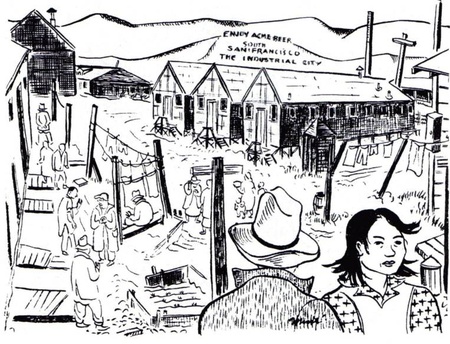

We can also observe this kind of mutual intervention of text and image in another picture.

This image is mainly concerned with hygiene in the camp. You can see three cabins made of wood. Miné Okubo used thin brush strokes which are fading into the background to suggest that there are more units than these three in the foreground. Grass is spreading between the wooden planks that form the floor. In addition to that we can see three women sitting in the cabins. Those cabins do not have any doors—they are completely open. The woman on the left hand side has set up a wooden plank in front of her cabin. The woman on the right hand side has pinned a curtain in front of her cabin, and only her hands and feet are visible. The woman in between those other two does not have anything to “close” her cabin. She has spread her skirt over her knees and is covering her face with her hands.

The picture, taken out of its context, would be hard to understand. But if we do have the whole book in front of us, we can conclude that the room in the picture is probably a toilet room, even though no toilets are depicted in this picture. Two pages before the image in discussion, Miné Okubo has presented the flush toilets to the reader. This looks almost identical to the room in this picture, but the cabins are partitioned in two toilet units instead of one.

Now let us have a closer look at the relation between text and image. The text underneath the picture says:

“Many of the women could not get used to the community toilets. They sought privacy by pinning up curtains and setting up boards.”

Here she describes this room as the “community toilets”. But is the flush toilet facility the same as the community toilets discussed in this picture? It could also be the case that there are different kinds of facilities within the camp. But she does not tell us for sure.

These two sentences in combination with the pictures reveal a lot about the sanitary equipment in the camp, it is something that Dorothea Lange would never have been allowed to show in her photographies.

Hygiene and privacy in these facilities were a huge problem. It was not only very dirty and smelled horribly; even the mere usage of these facilities was humiliating. I would be ashamed if I had to use a toilet which does not have a door. The women in this picture try to solve this problem by setting up boards and curtains and thereby try to gain as much privacy as they can. This picture shows that the women try to get along in this camp even under these conditions. What I found striking about the picture was, that if you look at it without knowing the context or the comment added on the bottom of the picture, you would have a lot of different options of how to interpret it. The only person that suggests that something is wrong is the woman in the middle of the cabins. She is covering her face, either because of the horrible smell in the room, or because of the shame, having to sit on the toilet without having any chance to cover herself properly.

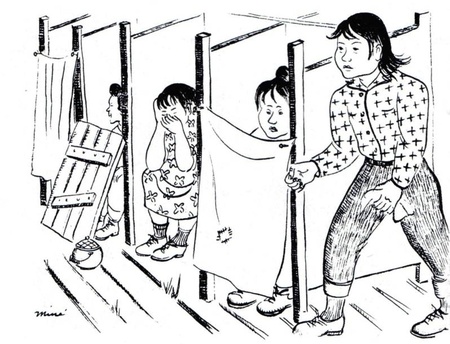

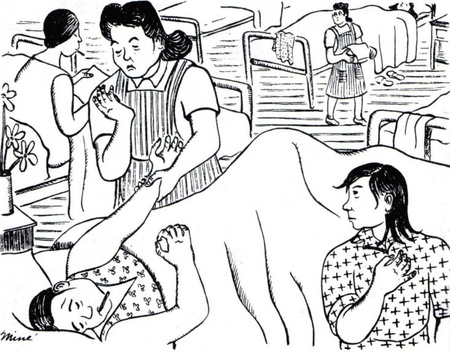

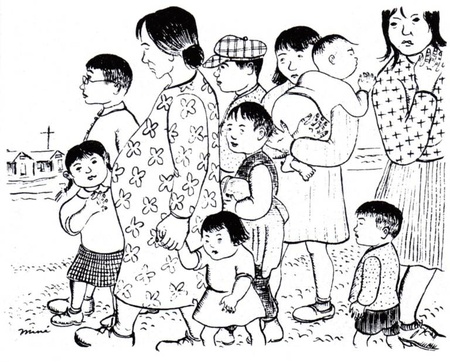

The last text and image combination I would like to discuss is the double page on the pages 162 and 163. This image deals with health care in the relocation center. The picture on the left hand side shows a scene in a hospital. The picture on the following page shows a pregnant woman surrounded by many children.

The picture on the left shows several hospital beds occupied by sick people. In the bed in the foreground lies a Japanese American man with a clinical thermometer in his mouth. A nurse is holding his arm and checking his pulse. Next to the bed is a small table with a flower placed on top of it and on the right hand side we can, like in every other picture, see Miné Okubo. She is watching the scene with a worried look on her face. The text under the image says:

“The army type hospital had 175 beds. It was directed by Caucasians but was staffed largely by evacuee doctors, dentists and nurses. The dead were sent to Salt Lake City for cremation, and the ashes were held for burial until the day of return to the Bay region. The cemetery at the far end of the camp was never used.”

The first sentence does already tell us a lot about the hospital. Thousands and thousands of internees were held in these camps, and they only had a small hospital consisting of 175 beds. These are very few if we compare it to the overall size of the camp. Due to the missing health support and the small note concerning the burial customs within the camp, we can also assume that the death rate was very high.

The second picture shows a Japanese American woman surrounded by seven children. The woman seems to be in her final month of the pregnancy, and by the arrangement of the picture, we can assume that she is on her way to the hospital to give birth. She looks very old and unhappy. There is only one sentence written underneath the picture:

“The birth rate in the center was high.”

Miné Okubo only gives us a fact. The image does not reveal anything about the children. They could be the children of some other person, only following her around out of boredom, or they are following their mother to the hospital. But the text underneath suggests that these children all belong to this woman. The families in the camps were destroyed and family hierarchies suffered under the conditions as well. The women could not care for their children as they would have done when they were living a normal life, and still there was a high birth rate. What I found disturbing was not only the image itself but the arrangement next to the image of the hospital and the description of the burials. If they had such a high birth rate, and only such little medical support, we could imagine that they also had a high amount of miscarriages or illnesses the mothers suffered from.

This works with almost all image and text combinations in the graphic novel. The images themselves give small and subtle hints to what is going on in the camp. But if we only look at those images we could assume that they are just simple studies without a clear message behind them. Some of them hint in certain directions, but others could also be interpreted as positive, almost cheerful images without further criticism. But the text underneath the images is the key to Miné Okubo’s interpretation of the events. She decided to phrase the words carefully, avoiding bluntness or direct accusations. In most cases, the text is constructed in a rather descriptive manner, with the unspoken demand towards the reader, to make him or her read between the lines. It is a very thoughtful and emotional way of describing her experiences in the camp. She makes the reader think about the camps and the injustice that had been done to the Japanese American citizens.

Even though I have chosen three examples that depict the most unpleasant conditions in the camp, I would still like to point out that this is not the only kind of image that Miné Okubo presents to us. She also showed happy, almost comical scenes in the camps, like the sleeping men, the art exhibition or the plants that suddenly pop out of nowhere in unexpected places. She highlighted several different aspects of camp life in her graphic novel, using her unique art style. Nevertheless, by adding the comments underneath the scenes, she says a lot without saying anything. The reader feels with the people in the camp—their suffering, their anger and their joys. This is not “just” a graphic novel. This is a piece of art, and I can recommend it to everyone.

Mine Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946)

© 2010 Bettina-Jennette Bierwirth