Brazilian nikkeis and their families began to arrive in Japan massively in the early 90´s pulled by the dream of saving money working here for a few years and, at the same time, pushed out of Brazil because of the Brazilian economic situation back then.

Over the years these temporary workers in Japan, known as Brazilian dekassegui or nikkei burajirujin, became second-class citizens, employed to fill in the gaps of labor force in the Japanese industry and living in Brazilian ethnic enclaves around these industrial areas.

Among so many other examples, this movement is implicitly connected with what we call now globalization, which is, in a sense, a system that transfers wealth from one part of the planet to the other, moving impoverished populations from the fields to the towns and from there to far away countries.

In Japan, the combination of economic maneuvers created to maintain its society’s lifestyle and the economic situation around the globe has charged a very high price. So far it’s been almost twenty years of sudden, challenging changes to its people and to the nikkei immigrant itself.

One of the issues resulting from these movements of populations around the globe is the issue of mixed ethnicities in Japan.

One of the key events for this change began at least one hundred years ago when people from Japan started migrating to the Americas, helping creating a mixed ethnicity in the areas where they settled.

This time, however, it is these migrant’s sons, grandsons and so on who are gradually bringing their mixed ethnicity back into Japan, a country where most citizens have a physical appearance that, at least in a first look, seems to be ethnically homogeneous.

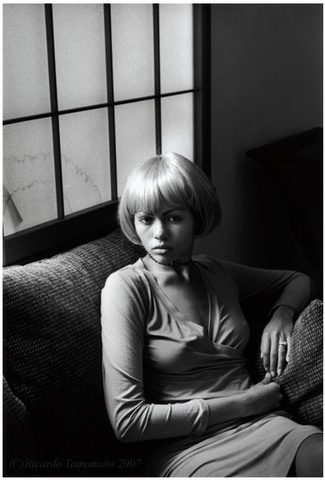

This idea of a homogeneous ethnicity or homogeneous appearance in Japan, recognized even by its former Prime-Minister Taro Aso, helps emphasize the ones who are different, even when the difference is subtle, which is specially the case of “haafu” individuals, generally considered as those whose appearance is some kind of Japanese-Western or Asian-Caucasian mix.

And in order to talk about differences in physical appearances and the conceptions related to them I would like to focus on a group which, I believe, exemplifies well some of these conceptions: the Japanese-Brazilian “haafu” models in Japan.

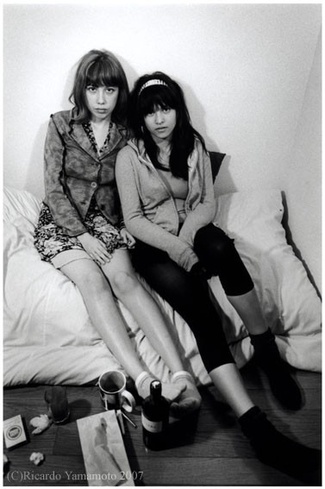

To me these young boys and girls represent a very interesting case in this whole topic because they are ”haafu” whose image reaches society’s main stream through the mass media in a close, realistic context and whose personal backgrounds, in most cases, are of dekasseguis and immigrants who once lived or even still partially living in the margins of this same society.

As the manager from a Tokyo modeling agency specialized in “haafu” models well described to me, in the advertising world the image of the “haafu” model represents a superior, international version of the Japanese itself. If this is the idea that is being sold, people out there seem to be willing to buy it, specially the younger ones.

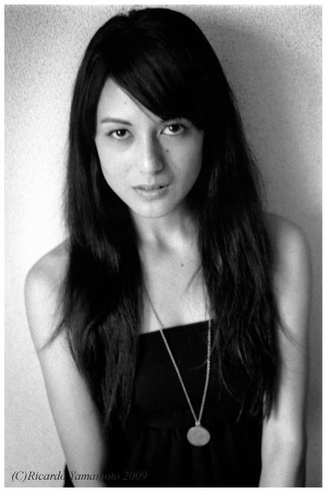

According to another manager from a different agency, a year ago Japanese-Brazilian “haafu” models occupied about 5% of the segment in Japan, a proportion that tends to increase since they are plenty, they already live here and are more or less acquainted with the country, making the whole process of casting, training and accommodating cheaper and faster for the agencies. And it usually pays off. At any given day in Tokyo we can see them everywhere, printed or broadcast, in visually flattering situations.

On TV and on pages of magazines they are products employed to help materializing ideas that promote and sell, but while performing this primary task, they also end up helping to construct a positive, appealing “haafu” image to the eyes and minds of the consumer, in other words, to the eyes and minds of the society.

It is also interesting to note that specially in the world of media and industry, rather than an ethnic condition, being “haafu” is an ethnic idea that also includes individuals who are not biologically “haafu” but nevertheless can be sold as so.

The example of Japanese-Brazilian models also implies that the idea of “haafu” in Japan is associated not only with social but also with geographical conditions. In most cases, the Japanese-Brazilian models are former factory workers or have their family working in factories in Japan. When one of these models leave Tokyo and go visit her parents and friends in Brazilian ethnic enclaves such as Hamamatsu city, Aichi, Gunma, Gifu prefectures or any other highly industrialized area, the Japanese-Brazilian model is not regarded as “haafu” anymore. Instead, she “becomes” nikkei burajirujin because for the common citizen down there that is the category in which her physical appearance fits in, in the first place.

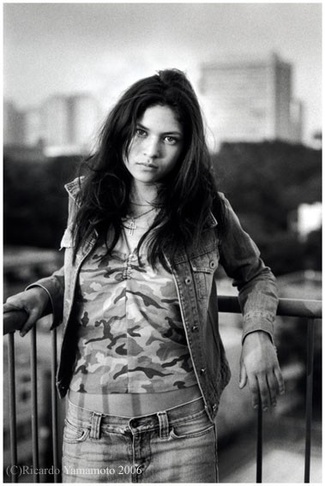

And then, when this nikkei burajirujin who went visiting her parents is back in Tokyo, walking around high-class areas such as Azabu or Aoyama, no one will mistake her for a factory worker anymore. Because in Tokyo she would be back to the social and geographical conditions in which she is recognized by the surrounding society as “haafu”.

That being said, this work aims to call attention to the fact that in the changing ethnic conceptions in Japan, the same different physical appearance can be regarded differently in great part due to the context it is presented to the common citizen by the mass media.

The American writer George Trow once noted that in a society there are many grids that hold culture together, with the individual grid at one end and the mass media grid at the other. And when the concept of mid distance falls away, the individual is relating and comparing himself directly to the mass media and to the world that is presented by it.

So, while Japanese-Brazilian “haafu” models can be a good example of the many ethnic bridges that may gradually lead to a transnational conscience in the Japanese society, their image also puts in question the kind of transnationality that is being constructed. How much of it is based on reality? How much of it is based on imagination?

* Photo exhibition "At Mid Distance" is at the Brazilian Restaurant Churrascaría Que bom! in Asakusa, Tokyo through February 14, 2010.

© 2010 Ricardo Yamamoto