The first Japanese arrived in Chile at the end of the nineteenth century. The development of the Nikkei community, therefore, has evolved for more than 100 years. From the point of view of the Japanese influence in Chile, we can divide the period of Nikkei development into the following stages:

• Before 1900: We have no information regarding the arrival of the Japanese

• 1900-1950: The Issei period (Meiji-Taisho)

• 1950-2000: The Nisei period

• 2000 to the present: The Nikkei period

Before 1900

To better understand the multiracial and multiethnic influences that the Japanese and Nikkei experienced at the beginning of the twentieth century, we should recall that after the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the next great wave of immigrants to southern Chile consisted of Germans, who began to arrive around the 1850s. Also during this period British influence was expressed through the nitrate mining companies in the north, while the French made their influence in the arts.

Before 1900, particularly during the 1840s, a group of Japanese sailors arrived in Mexico and some made their way to Chile. On the other hand, the first census taken in Chile around 1875 had counted only but a few Japanese. We lack reliable data, however, to comment further.

By 1892, the Ryujo Maru Sailing Vessel of Instruction made an official visit to Chile and, during its stay in Valparaíso, buried a dead sailor in the Dissidents Cemetery there. His grave can still be found in the cementery today.

1900-1950

Japanese activity developed around the employment opportunities that Chile had to offer. In the beginning such job opportunities were found in mining activities in the north and agricultural activities in the south-central area of the country. Afterward some Japanese established themselves in Chile and welcomed other Japanese who arrived later.

Given the difficulty with the language, many Japanese continued with the same kind of employment that they had enjoyed in Japan, or they easily developed new skills while in Chile. With these employment opportunities, there was no great need to learn Spanish. Examples of such work included the hairdresser’s shop, photography studio, and stores.

In the first half of the twentieth century, from the point of view of the Japanese, the recently arrived Issei had the most influence in Chile; such influence was shaped by the Meiji and Taisho of Japan. Most Japanese in Chile at this time continued to embrace the old country, expecting to return after achieving their economic objectives.

Until just before the outbreak of World War II, some Japanese who were financially able sent their children to study in Japan. Others made the effort to teach their children Japanese. The great majority, however, settled throughout the country and married local women, and their children studied in Chilean schools. In the case of Chile, there were no Japanese schools like those found in other countries where Japanese immigrants arrived in larger numbers.

In the world of sports, the Issei influence is direct, for they introduced baseball to Chile, especially in the north and center of the country, as well as Jujitsu in the Chilean Police force and Chilean Navy. In addition to baseball the Issei also played the ever popular soccer. Baseball has practically disappeared in Chile despite its soaring popularity that had lasted until the 1960s.

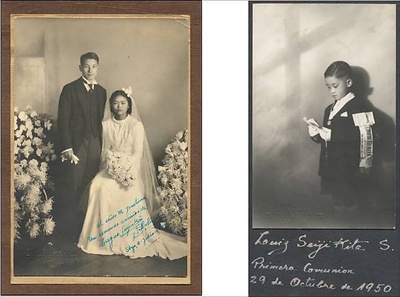

Without a immigration accord between Japan and Chile, the Japanese who emigrated were few in number, and for that reason, in terms of religion, the majority followed the official religion of the country, Roman Catholicism, which was reflected especially in the wedding ceremonies, the raising of children, and funerals.

With respect to food, many Japanese men arrived alone, meaning they had little choice than to adapt to the local foods. Nevertheless, the few Japanese women who came to Chile with their husbands began to prepare meals in the Japanese style, using local ingredients. Chile was abundant in fish, shellfish, and vegetables; therefore, the Japanese were able to consume more than just meat and kidney beans but also sashimi and grilled fish. Rice also was part of the local diet, so “gohan” remained part of the daily meal for the Japanese in Chile.

During this period the Japanese Legation protected the interests of the immigrant population in Chile, but, at the outbreak of World War II, when Chile broke off diplomatic relations with Japan and declared war, the Japanese were relegated to towns far away from the major urban centers. Although such an act did not facilitate even greater restrictions of movement, the Japanese and their familias had to leave smaller localities to protect their interests, congregating in small communities such as the Hacienda Caupolicán in Rengo, or working in remedial jobs that provided some form of living. Most of the immigrants who lived in such places opted to remain after the war, focusing on economic activities that allowed them to maintain their families.

Another change due to the war was that the Japanese and their descendants began to suffer a classist attack promoted by films and propaganda coming from the United States. This promoted acceptance of the idea that the children of Japanese immgrants were going to be brought up in the very country – Chile – that welcomed them. Parents would raise their children in the educational system of their new home. They began to give up on the idea of returning to Japan or of sending their children to study in Japan. Parents began to send their children not only to primary school, which was obligatory, but also to college. A large number of Nikkei study at the university for careers in engineering, nursing, medicine, business, architecture, etc., and are becoming an important group of professionals in Chile.

1950-2000

With the end of World War II, Japanese companies increased their activities in Chile. The Japanese who were relegated to the small towns and cities were available to work in those Japanese companies, while others developed their skills in activities appropriate to the scope of independent businesses, including agricultural and professional careers. When this period began the Nisei still continued the practice of following in their parents’ footsteps in terms of employment, finding work in the hairdresser shops, photography studios, and stores, but this pattern would soon disappear when many of the Nisei entered collage and later became professionals after graduating. They earned a good reputation as hard workers in local as well as Japanese companies.

In sports they continued playing baseball (for Club Nisei, among others), although the majority began to adapt to Chilean sports, especially soccer. With the arrival of television the trends are global in nature; the Japenese promote Judo and Karate.

The Nisei practice Catholicism as their religion

In terms of food the Nisei continue to follow the culinary traditions of their parents: sashimi with gohan, okoko (tsukemono), including miso that some Japanese prepare with kidney beans, garbanzos, and beans before the introduction of soy. Alcoholic beverages include the pisco (whiskey) and white wine (with fish) and red wine (with red meat). Soon Japanese cuisine began to spread throughout Chile, as the Nikkei, Chileans, and foreigners traveled through the country in search of Japanese food; afterward Japanese food appeared too in the United States. The ingredients for Japanese food began to arrive in large quantities, and the number of Japanese restaurants increased raidly. Today in Santiago there are hundreds of Japanese restaurants, many offering “delivery” service.

Adaptation continues its course and, with the introduction of the avocado in California, Chile also develops its own cuisine. As you know, wine was introduced to Chile by the French in the nineteenth century, but it was not until the 1980s that the technology was modernizad and Chilean wine became known world-wide. Today Chile relies on many grape stocks, white and red. This has allowed Japanese food to be combined with white wines and, in the case of sashimi and sushi, not only with white wines but also red wines, such as Pinot Noir.

With no official immigration to Chile, the number of Japanese and Nisei was quite low. For this reason, most descendants entered into mixed marriages, and soon their children were educated primarily in the local schools. This meant that the Nisei and Sansei would rapidly lose the ability to speak Japanese and, quite naturally, also lose many customs. In places far from the capital, the opportunity to mingle with other Japanese or with Japanese culture was practically nonexistent.

In this period a few official organizations and institutions were formed to protect Japanese and Nikkei interests, such as the Japanese Beneficence Society, which was the primary link with the Japanese government by way of the Embassy of Japan (established in 1954). The Consulate of Japan kept track of the property of those Japanese living in Chile, while the Japanese Society took on the role of looking after the interests of all the Japanese in the country.

2000 to the Present

The world-wide spread of the Internet echoed quickly through the Nikkei community, which is part of the globalizing trend in all walks of life. Like everywhere else, the discussion centers around who are the Nikkei, what role do they play in sociocultural globalization, etc. The Nikkei community in Chile establishes relations with other Nikkei groups in the Americas as well as with other international groups interested in the development and preservation of Japanese cultural values.

In this period the differences between generations are more pronounced and more frequent: between the Nissei and earlier generations, between the recently arrived Issei and those who arrived many years ago, and between the recently arrived Issei and the Nikkei, which is to say, the simple generational differences also add to the development of these communities in their own countries as well as their influence today in other countries.

We could say that in the case of Chile, the generation that dominated the second half of the twentieth century was the Nisei generation, and that the beginning of the twenty-first century is giving way to Nikkei dominance, which is already sufficiently influenced by a cultural globalization that advances at a rapid pace.

With still so much unkown in the last decades of the twentieth century, but with the growth of impressive and rapid communication systems, we find ourselves in the dilemma of how can we the Nikkei contribute to Japan’s greater participation in this era of sociocultural globalization.

* * *

>>The collection "Desarrollo de la Comunidad Nikkei en Chile" in Nikkei Album was developed based on this article.

* * *

* The above article is the result of the discussions that took place at the session “Nikkei Diaspora: Nikkei Migration in the Global Society” in the workshop organized by Discover Nikkei at the XV COPANI, held in September 18 in Montevideo, Uruguay.

© 2009 Roberto Hirose