The five of us boarded our flight to Mexico with little knowledge and much anticipation of what awaited us at our final destination. Ken, another group member, was on a separate flight; he was to meet us in Mexico. Akiko, our delegation leader, had left a day earlier. We called ourselves “Choode (brothers and sisters) Without Borders,” because our trip to Cuba was not just a vacation: It was a mission.

The seven of us came from different professions and cities. Akiko was from the East Coast; the rest of us resided in cities across Los Angeles County. Among us were a teacher, an office manager, a researcher and myself, a journalist. We came from different paths in life but shared a common goal: As Americans, we wanted to support the Cuban Okinawans — or Cubanchu (pronounced ku-bahn-chu) — as they commemorated 100 years since the first Okinawans arrived in Cuba. Our mission went deeper, however. We also wanted to help younger Cubanchu in their quest to rediscover their roots.

I first heard about a possible commemorative trip to Cuba last April when Wesley Ueunten, Kaua‘i native and a professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University, made a presentation on his trip to Cuba to the Los Angeles-based Okinawa Association of America. He had traveled to Cuba in January with a Bay Area group and had met the Cubanchu families. Wesley shared compelling stories about the history of these families and their feelings for Okinawa. As a journalist, his stories further piqued my curiosity because of the United States’ long-standing policy on Cuba. And, as a Sansei Uchinanchu, I was excited to hear that the diaspora included Cuba. I wanted to know more about the Cubanchu and to see how they lived. Wesley told me that Akiko was trying to organize a group for a trip in October, so I e-mailed her. The details were scant, but that didn’t matter. I wanted to go.

“The date planned is Oct. 27. The Uchina-Cubans were originally planning to have their modest celebration themselves on the date. When I learned through my friend that we, Uchinanchu in North America, were the Uchinanchu that they were interested to meet most, I knew that we have to go see them,” Akiko e-mailed me.

Mindful of the cold political climate between our two governments, I was touched to hear that they, too, wanted to meet us and that politics didn’t matter. I felt compelled to take the trip even though I knew very little about Cuba.

The next few months were spent trying to recruit people for the trip. I also researched Cuban migration on the Internet. Although there wasn’t much there, I did manage to learn a few facts.

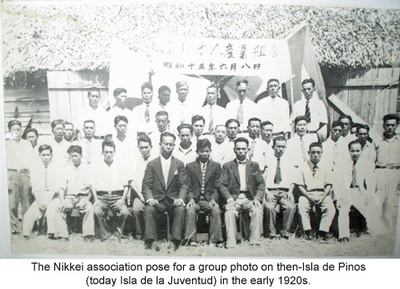

The first documented Okinawan immigrant to arrive in Cuba was a man named Masaru Miyagi. He reportedly came from Shioya, Ogimi-son, in northern Okinawa. Miyagi landed in Havana in 1907 after stopping first in Mexico. He landed on Isla de la Juventud, or Island of Youth, (then known as Isla de Pinos — Island of Pines) in 1908. Isla de la Juventud, also referred to as “Isla” (pronounced iss-la) is home to Cuba’s Nikkei community. In the early 20th century, approximately 1,000 male immigrants from Okinawa and mainland Japan arrived in Cuba to work in the sugarcane fields. Cuba was not their first destination for work. Many came from Panama or Mexico and eventually left to settle in other parts of the world.

According to data collected in 2006, there are 215 Cuban Okinawans living in Cuba, most of them on Isla de la Juventud. They are descendants — some even sixth-generation Okinawans — of the 195 Issei who immigrated to Cuba between 1920 and 1940 to work in the sugarcane and agricultural industries. Wives of the married men were able to join their husbands on the island. Many of the single men who stayed married Cuban women and settled in their new home, much as other Uchinanchu immigrants did around the world.

By the end of summer, we had assembled a group of Uchinanchu and Uchinanchu-at-heart committed to the mission. Our next task was to apply for our travel license through the Office of Foreign Asset Control. Because of the U.S. embargo against Cuba, travel there must be authorized by our government. Unless a trip falls under certain categories, such as research, academia, public performance and humanitarian projects, travel is banned and violators are subject to fines. Fortunately, Akiko found an attorney who helped us file our application.

With our filing completed and just over a month before departure, we focused on the second part of the mission: fundraising and gathering up donations. I tried to remain optimistic, but I wondered how successful we would be in for our donation drive. Would anyone donate? Would the community be interested in the story of Okinawan immigration to Cuba? More importantly, how would they feel about supporting a trip to Cuba, a country that was once an ally but is now considered a foe?

Much to my surprise, dozens of people supported our plans. Many Uchinanchu Americans generously supported our cousins in Cuba with monetary and personal donations of history books, Okinawan music, fabrics and DVDs. OAA vice president Pedro Agena even donated a sanshin that was a family heirloom.

As a final effort to raise funds, we held a screening of a documentary on the Cuban Okinawan experience at a Peruvian Nikkei restaurant in Gardena in October. The documentary was produced by Shinichi Maehara of Okinawa’s OTV. Again, I was pleasantly surprised by the packed house and the interest shown by the Los Angeles community.

The documentary centered on Benita Iha, a Nisei Cubanchu who wrote a book about Cuba’s Issei immigration experience. She titled her book, “Shamisen” in memory of her father, who enjoyed playing the sanshin and singing.

Benita’s father, Kamaichi Iha, left Okinawa for Havana in 1924. Her mother Kame later joined him. Although they had five children in Okinawa, they were not able to bring them to Cuba. Like so many immigrants, they had always hoped to return to their homeland. Unfortunately, it never happened. In 1930, the Ihas moved to Isla de Pinos (today Isla de la Juventud), where they worked on farms with other Cuban Issei and settled into a new life in a new country where they raised their four Cuban-born children. The documentary followed Benita’s dream of getting a copy of her book to her older brother in Okinawa. The film also profiled other families living on the island with similar stories.

Benita Iha(right), who authored the book shamisen," in memory of her father Kamaichi Iha, pictured with her sister Maria. (Photo by Lesley Chinen)

The highlight of the evening was the reading of an e-mail from Benita. She had been told about our event and sent her appreciation. Her e-mail read:

“To the organizers and participants of tonight’s Wakatay Night from La Isla de la Juventud where the 100th anniversary of Uchinanchu immigration will take place, we would like to express our gratitude and joy that you are remembering us tonight. This evening our hearts will be together as we remember the shamisen [sanshin]. We await you all in Cuba. Ichariba Chode!”

We learned that the Cubanchu dance team performed in their street clothes, so with about a week to go before our departure, we used our monetary donations to buy Eisä costumes and everyday necessities for the Cubanchu. The six of us in Los Angeles divvied up the purchasing duties, buying things we knew Cubans could use, things Americans take for granted, such as aspirin, notebook paper and soap. These are luxuries for Cubans, who live on a fixed income.

Meanwhile, I began gathering video messages from kenjinkai across the country and from individuals who had previously met the families we would meet in Cuba. The messages were meant to show the diversity among the North American kenjinkai while also showing our support for their centennial. I received congratulatory messages from the Dallas Champuru Society, the Okinawa Association of America (Los Angeles), Okinawan Association of San Francisco, the Chicago Okinawa Kenjinkai and the Hawaii United Okinawa Association. I was also contacted by Sandy Maeshiro, who had met the Nikkei families on Isla in 2001 while on a goodwill trip with the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations. I thought her message, along with footage from that trip, would be a nice way to show the Cuban Nikkei that they were not forgotten.

At our final “Choode Without Borders” meeting, we divided up the items we were taking. Our luggage was limited to 50 pounds per person. When we checked our bags in for the flight to Havana, the counter agent told us we had just made the weight limit.

With a sigh of relief, we boarded our flight to Havana.

*This article was originally written as a special to The Hawai‘i Herald.

© 2008 Lesley Chinen