A good friend of mine just got her American citizenship. It was a bit surprising that she didn’t have it already, considering how long she’s already been a part of American society; but when I asked, ”Why now?” she explained, “I wanted to make sure I can vote [this year].” As a person who is very conscious of what’s going on in society, she has been dead set on having her voice heard through her vote in the upcoming presidential elections in November.

Let me explain a few things about “citizenship,” for those of you reading this column outside of the United States. Gaining American “citizenship” allows foreign-born American residents to have equal rights and liberties held by those who are natural-born Americans. “Citizenship” protects the “basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled,” as guaranteed by the United States Constitution.

As for the tangible differences that a Japanese person who gained citizenship experiences, there is the replacement of one’s passport into an American passport. The person must renounce their passport issued by the Japanese government, and replace it with one issued from the American government. It is because “to gain American citizenship” = “to gain American nationality.”

Contrary to the laws in Japan, anybody born on American soil automatically is an American citizen. The way citizenship is interpreted here is vastly different from Japan, where you do not get recognized as a Japanese citizen unless one or both of your parents are Japanese.

Cases of foreigners gaining Japanese citizenship are few and far in between. In most cases, these individuals are Japanese-born, but with non-Japanese parents who are considered “Zainichi Gaikoku-jin” (resident aliens in Japan). Another way they can gain citizenship is by marriage (with a Japanese citizen). In some special cases, a foreign individual who has served a certain form of distinguished service for Japan might be considered for Japanese citizenship—but, as you can see, the parameters that allow for naturalization are very limited. The process is so difficult because the Japanese government refuses to recognize immigration.

On the other hand, America—sometimes referred to as the “Big Country of Immigrants”—has already seen over 80,000 “brand-new” American citizens this year. As long as you remain a law-abiding resident of the United States, gaining American citizenship is relatively easy.

Here’s one example: a Japanese person, Mr. A, wanted to attend an American university, so he came stateside on a student visa, and graduated from that university. After graduating, and before his one-year interim visa expired, he landed a stable job, and his employer sponsored him to switch over to a worker’s visa. Under the law, a work visa is good for up to six years. During that time, again with the sponsorship of his employer, he applied for a Green Card. After working for five years, he obtained his Green Card and became a permanent resident of the United States.

Mr. A liked America, and had vowed to permanently reside in the states. Of course, with his Green Card, he had the right to live in America for as long as he wanted—but then again, a Green Card is something made specifically for foreigners. Perhaps it’s inevitable to be treated unequally at times, compared to American citizens. Mr. A thought about his future, and decided that he was going to apply for citizenship. However, in order to apply for citizenship, you must live in America for at least five years after gaining their Green Card. Filing your tax returns annually becomes proof of your residency.

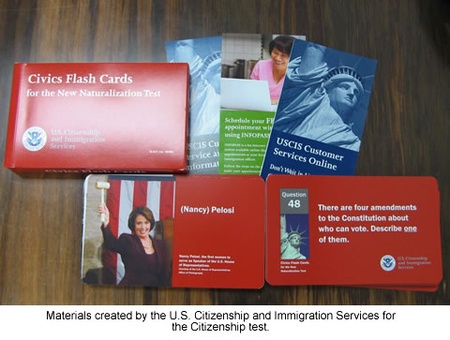

So Mr. A, who simply followed the rules while residing in America, and spent his five years with his Green Card without any arrest records, gained his right to apply for citizenship. After submitting his paperwork to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Mr. A attended free “Citizenship Courses” at a local adult school in preparation for his interview exam. During this interview, applicants are asked ten relatively simple questions about American history, government, constitution and such. If you answer six questions incorrectly, you are disqualified.

The passing rate for the exam is over 90%. Mr. A, who had been studying for it, passed easily. FBI investigations were completed as well, and three months later, he happily headed out to the inauguration ceremony to be sworn in as an American citizen.

So, to put a long story short, in Mr. A’s case, he was able to get sponsorship (guarantor of income) from his employer, and eventually gained his citizenship. However, the most common way that citizenship is obtained is when an American citizen personally sponsors his or her non-American spouse and/or family member, so that they can obtain their Green Card, and eventually, their American citizenship. In this case, the process is much easier and takes less time to obtain permanent residency and citizenship in comparison to Mr. A’s case, whose sponsorship was employer-based.

However, just because a Japanese individual has cleared all of the criteria required to apply for American citizenship, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they are inclined to apply right away. Part of it has to do with the fact that, unlike immigrants from other developing countries, most Japanese are not eager to bring their family members over to the states and become a sponsor for them. Another part of it has to do with changing their Japanese passport to an American one—there seems to be some feeling of resistance against becoming completely “American.”

There are several people that I know who have been living in America for several decades, but remain permanent residents with Green Cards. Actually, almost everyone I know is like that. When you’re a Japanese person living abroad in America, your love for Japan tends to grow stronger, and since Japan is just as great of a country as America is, I can understand this sentiment of not wanting to let go. What, then, drives some Japanese people to “gain American citizenship”—to decide to completely “become American”? In part two of this column, we will take a look at the stories of Japanese people who have obtained, or are in the process of obtaining, American citizenship.

© 2008 Yumiko Hashimoto