My first car was a Toyota Tercel—frosted mint (a pale whitish-green color), two doors, and fairly bare-boned. It didn’t have power windows or doors, but it was all mine. Practical and functional, I had it for ten years before I traded it in for a Toyota Matrix. I rarely had any problems with it...dependable, it took me where I needed to go.

My parents purchased it for me using part of my father’s reparations money*. The reason why they purchased it was primarily practical—so my parents didn’t have to drop me off and pick me up from school. Without the $20,000 check from the government, they likely wouldn’t have been able to buy it for me, at least not in cash. I chose the Tercel because we are a family of Toyota owners (a story I’ll save for another time), and it was the least expensive Toyota model available at the time.

I guess, in a way, it was a fitting way to spend that money. A car represents opportunities and the freedom to pursue them. Having my own car enabled me to go to classes on my own, visit friends and family, go to see movies, shopping, and other activities. I was able to venture out in the world on my own on my own time, not reliant on someone else to give me a ride.

Not that having my own car was all fun. Owning a vehicle comes with many maintenance and other responsibilities. It was in that car that I was involved in my first accident where I was the driver. My cousin’s young daughter was with me at the time. I wasn’t at fault, and it was a minor accident, but enough to require repair. It showed me how easily and quickly that freedom could be taken away.

Ironically, we were on our way to the Japanese American National Museum to see the America’s Concentration Camps: Remembering the Japanese American Experience exhibition. Luckily, the damage to my car, although expensive, was superficial, so we were able to continue on with our plans for the day. It was the opening weekend for the exhibition. It was incredible to see so many people there engaged and interacting. People were having Polaroid photos taken of themselves to include in binders representing the camps they were in during the war. Others were placing little plastic “barracks” onto layouts of the camp representing where they lived during the war. Impromptu reunions were happening all around us with friends reconnecting with each other after almost fifty years. Stories were being shared between generations of families about what it was like in camp, probably many being heard by their children and grandchildren for the first time.

Afterwards, we took a shuttle bus over to the Los Angeles Convention Center for the Family Expo that was coordinated by the Museum. It was so amazing to see how many more people were there as well. Organizations and vendors filled booths promoting their community projects and Japanese American-related products. Walking down those aisles was a revelation...to see so many people gathered together was inspiring. A year later, I started working at the Museum. At the end of April, I’ll have reached 13 years.

I am still inspired by the many stories and the Museum’s ability to bring together and connect people. In 2004, my husband and I attended the Museum’s national conference “Camp Connections: A Conversation About Civil Rights and Social Justice in Arkansas" in Little Rock, Arkansas. Nearly 1,400 participated. To be among those there and to be a part of all of the many activities is still one of the most memorable and deeply moving experiences I’ve ever had. It’s why I’m really looking forward to the next conference this summer in Denver, Colorado.

My parents don’t really remember anything about what happened in the camps. My father’s family was in Jerome, and my mother’s side was at Rohwer. They were both too young to know what was going on. They also attended the conference in Arkansas. Actually, they attended all of the activities, exhibitions, and screenings, but not the conference sessions themselves. For them, it was really about returning to the physical place. For me, it was a journey to connect to something of my family’s past. It was a very emotional trip for me to go out to the two camp sites and be able to walk around the grounds…to see the smokestack of what once was the hospital where my mother was born. I definitely felt the spirits of my grandmothers and other relatives that are now gone with me that day. That trip made everything that I had learned about WWII more tangible, more real. It wasn’t just physically being there, it was also hearing personal stories that I hadn’t heard before as I witnessed reunions and attended conference sessions.

I recently had the opportunity to tag along on a tour of the Redress Movement section from the Museum’s core exhibition, Common Ground. Mitch Maki, author of Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress, led the tour. Although after working so long at the Museum, I had heard many of the history and anecdotes, but I was pleasantly surprised to learn some new ones. The discussion he led also reminded me about something I had not thought of in years. Mitch explained that there were three main opinions within the community at the time when the Redress Movement was going on – to leave it alone and not stir up the past, to get an apology, and to get an apology with money attached to it. History shows that the latter is what came to be, but at the time, it was a source of major debate and argument. Mitch asked the people on the tour what they would have done. There was at least one person who answered for each view.

The discussion reminded me of my uncles and aunties discussing the reparations money...about whether to accept it or not. Some argued that it put a price tag on their freedom and that putting a price tag of $20,000 was insulting. I think, in the end, all of them eventually got their checks, but this story reinforces my personal connections with the work that the Museum does. This is what is so important in the Museum’s approach and the work that we do...providing the opportunity for our community to tell our own stories, from our own perspectives.

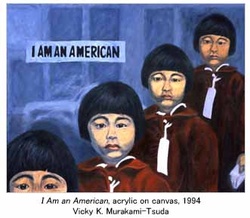

One of the classes that I took (which I was able to drive to on my own) was an Intermediate Painting class. We were given an assignment to do a painting using collaged images. I chose to use images from the Japanese American “evacuation” period. As I worked on the painting in class, an older Caucasian woman who was also in the class told me with a sympathetic tone, “It was really a shame what happened, but it was for their own safety.” It astounded me to think that this woman in California, fifty years later, still believed that. Because of that incident, that painting remains very personally important to me. Sometimes, when I feel overwhelmed and frustrated at work, all I have to do is look at that painting.

My Matrix is now five years old. It’s been fun to drive, but still a very practical car...and so far, knock on wood, hasn’t had major problems. Although it doesn’t have the same transformative ties as my first car did, it does have its own share of stories to tell.

*This year is the 20th Anniversary of President Ronald Reagan signing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, a bill that authorized a presidential apology and a monetary redress payment of $20,000 for each person still alive at the signing of the bill who were forcibly removed from their homes during the war.

© 2008 Vicky Murakami-Tsuda