A quiet revolution is underway, led by young Japanese-American visionaries who are redefining urban fashion on their terms. Their mediums are varied, and their approaches multi-hued, but collectively they represent a new brand of creativity and entrepreneurship that would make their Issei ancestors proud. They are Nikkei fashion designers who have chosen the medium of textile architecture to express themselves and their dreams.

You might not know that the Asian American T-shirt underground was launched from a single-car garage in suburban Gardena, California, but college students nationwide do. Ryan Suda, aka “the Godfather of T-shirts,” started his Blacklava clothing line in 1992 as a surf brand, and it gained a slow but steady following in the Southern California Japanese-American community. But his business didn’t reach a larger audience until he pressed up a simple T-shirt that read “Asian is Not Oriental.” Based on an anonymous poem he heard in his Asian American Studies class at Cal State Fullerton, Suda wore the shirt while on tour with an Asian American college theater group, and audiences went wild. He started selling them out of a backpack after shows, and the shirt quickly became a political phenomenon and Blacklava classic. The current incarnation of Blacklava was born.

“I realized I could tap a market that no one else had. Asian American students were getting inspired from their classes and the political theater shows we were doing, and my shirts could reflect that,” the 35-year-old Suda said from the Torrance headquarters of his online business, Blacklava.com. Besides shirts, Suda’s store is “an Asian American one-stop shop,” peddling everything from chapbooks to DVDs to taiko bachi. Blacklava.com proudly sells “sweatshop-free products,” and offers space to a range of Asian American artists and writers who need a virtual storefront for their wares. He still tours the country with his shirts, this time on the Nikkei matsuri and Asian American student circuit: Tofu Festival and Nisei Week in Los Angeles, Nihonmachi Streetfair and Cherry Blossom Festival in San Francisco, the API Spoken Word Summits, East Coast Asian Student Union Conference, Midwest Asian American Student Union Conference, and other Filipino, Nikkei and API events.

“Over the years, my business has gone through many challenges. My current challenge is accounting and advertising. There’s been many periods where I think, ‘how much shi**ier can it get??’ Then I tell myself to buck up, it’s not really that bad,” said Suda. “It’s always nice to go around and see people wearing my Blacklava shirts. The more random the situation, the better.”

Kenshin Ichikawa never meant to end up in fashion. His degree from Columbia University was in visual arts, and the Tennessee native worked in graphic design and fine arts after moving to New York City. But when partners Chiu Liu and Matt Ting came to him with the idea to create an American men’s brand with international appeal, he “jumped in without thinking.” MATO (or “target” in Japanese) was born. The pan-Asian American company first specialized in graphic T-shirts, then expanded into outerwear—mostly military-style jackets and pants. Sold successfully in Japan and stateside, MATO was acclaimed by publications like Complex, King Magazine, and Sportswear International before its gradual dissolution. From its ashes came lessons and a renewed entrepreneurial and artistic drive for artist Ichikawa.

“In all aspects of my life, I’m exactly in the middle of Japanese and American. So throughout everything, I’ve tried to maintain that balance,” said the 27-year-old designer, who cites avant-garde Japanese fashion pioneer (and Adidas collaborator on the “Y-3” line) Yohji Yamamoto, couture designer Issey Miyake, Harlem Renaissance painter Romare Bearden, and graphics-heavy women’s line Aem’kei as a few of his fashion and artistic inspirations. He met business partner Erik Marino while designing young boy’s clothes for hiphop brand Akademiks, and their partnership took flight. Since then, Ichikawa has established or led design for three separate companies: Lemar & Dauley (whose logo mimics the New York Lotto trademark) is a downtown sneaker culture line with T-shirts portraying basketball players, 80’s icon Ferris Bueller, and one inexplicable design that simply reads: “Strawberry Kiwi Baked Ziti.” All come in eye-popping Miami-inspired lime greens, pinks, and grey. Rocksmith caters to a cleaner, more high-price-paying customer, combining dip-dyed polo shirts and metallic-foil prints to create a style that might be termed “HRH Hip-Hop”—royal, yet “street.” Ichikawa also partners with Japanese-born jewelry designer Osamu Koyama, whose detailed renditions of boom boxes and microphones are handcrafted of fine metals.

“My aesthetic is clean, simple, with good quality and good details. Although it’s street savvy, the look is not so loud. I want to impress people with its subtlety,” said Ichikawa.

When Erika Varize’s grandmother Nana taught her to sew a simple skirt 20 years ago, she knew she was hooked. Even as her family moved around northern California, she held down a day job and continued to sew at night. Now 30, married and with two small children, Varize is enjoying commercial acclaim for her talents with a clothing line that has been featured in many fashion shows, and is the centerpiece of her new boutique on San Pablo Avenue in Berkeley, CA.

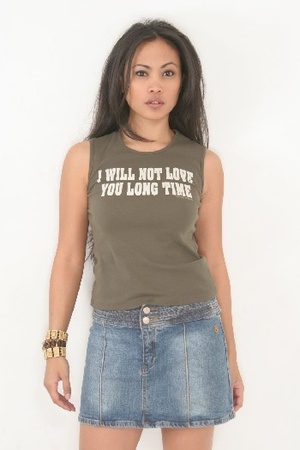

Of mixed African-American and Japanese American heritage, Varize draws from global influences —perhaps the best reflection of her Berkeley heritage. She centralizes the Japanese obi on sexy modern pantsuits and combines lush Asian fabrics, vintage cuts, and multicultural models to create a sophisticated look for her women’s line. The store’s trademark is made-to-order versions of the most popular Evarize styles, including the Jailynn Tank (a single-seamed sleeveless sheath with a slouchy halter neck) and the Angelina Top (a long top with dolman sleeves that is so popular, it’s now available as a dress). Customers pick their own fabrics and trims, and can pick up their custom garment in just a week to ten days. This do-it-yourself approach to custom couture is one of the perks of what Varize calls her “fashion café.”

“The customer becomes part of the design process. Sometimes full-figured women get intimidated by super-skinny mannequins. I’m happy we can accommodate all sizes, and make a custom garment that fits. The client may want a different hem, or no hem at all…when the finished product comes out, they feel like they designed it,” said Varize. “The emphasis is on a friendly environment.”

That’s one reason she chose to locate her shop in an up-and-coming area of west Berkeley rather than swankier (and higher-priced) Fourth Street or Solano Avenue. “It’s more bohemian,” said Varize. “We wanted to make the store friendly and for families.” Her children, six-year-old son Darius and four-year-old daughter Brooklyn, often keep her company in the neat cutting and finishing studio tucked behind her boutique. “Brooklyn already draws dresses she wants me to make for her, and she names them,” Varize said. “She’s inspired a new line of little girls’ clothes. They’ll be simple but beautiful, very girly, a little like things I wore in the 1970s—lots of white fabric and flowers, very pretty.”

Evarize also sells the clothing, art, and accessories of about 20 other designers. “When I started, I had no industry backing, no formal training; I have a degree from the school of Grandma. It was very hard to approach businesses to show my work, because my work is so personal. You don’t know how someone is going to react, whether they’ll like it. It’s intimidating. I have a love for local artists, and I wanted this to be a door to allow them to show their work to the public.”

Her husband (and business partner) Darryel Varize hoists huge spools of fabric onto a pickup truck out front. It’s a Monday, and the store is technically closed, but work doesn’t let up for these two young entrepreneurs. “My mother always said to me, ‘If the goal of your pursuit is not clear, you’ll lose sight of what you’re striving for,’” Varize said. “It fulfills me when my Japanese grandma attends a runway show, and I can see her pride.” And what about her African-American grandmother, Nana, who set her on the path? “She is blown away, but she always knew I would be at this point one day.”

Zulu Williams is a veteran at 37, a member of the hip hop “old-school,” a product of years of experience in the culture, alongside its founding fathers and mothers, its midwives and missing fathers, its beginnings as an art form and mutation into commodified product. His clothing company, PNB Nation, was launched in the cafeteria of New York High School of Art and Design (and named for a sign on the wall that read: “Post No Bills”), and grew into one of the oldest and most respected brands in the urban apparel industry. PNB’s popularity was measured by the number of imitators it spawned every season, and the longtime loyalty of its die-hard customers.

Williams’ Sansei mother and African-American father met as activist teenagers working in the Civil Rights movement. Raised in Harlem and schooled by stories of justice and struggle passed on by his grandparents, Yuri and Bill Kochiyama, Zulu was attracted to the power of art at age three by an uncle who “could draw anything.” He started practicing whenever he could, eventually finding a niche in early-80’s New York City graffiti culture.

“1982 was a renaissance year for hiphop—every kid wrote, or was b-boying, or rapping, or DJing,” reminisced Williams from PNB’s Manhattan office. “The generation before us was really multitalented, to where everyone was skilled in all the arts. But by the time we came along—the second generation, if you will—people were into specialization. My thing was graffiti.”

Graffiti of late has been praised, reviled, legislated, imitated, exported, and used in Pepsi marketing campaigns. But for Williams and his New York writing colleagues (“writing” is slang for spraycan painting), the motivation was simpler: fame and respect. Miniature Velasquezes and Diego Riveras in hooded sweatshirts, they plastered the walls of 60-foot-long subway trains with urban petroglyphs, sprinting from transit cops as they hastily finished sprawling memorial walls, Gotham cityscapes, and the ultimate self-promotional tool, the tag (a writer’s nom de guerre and territory claim).

hen came the government crackdowns and three-strikes laws. As they grew up, many of the best and brightest graffiti writers faced stiff adult sentences for their art, and decided to translate their skills into the legal (and profitable) T-shirt market. “After high school, around 1987 to ‘88, the last graffiti cars were phased out. A new medium, T-shirts, started to emerge. T-shirts were similar to trains in that they took your work all around the city. Lots of elements from the art went onto shirts. We just wanted to get our culture noticed. Lots was political, but not preachy,” reminds Williams.

The morphing of street graffiti into T-shirts and the larger urban apparel industry mirrors the music and culture’s overall inroads to the mainstream.

“In the early 90’s, downtown met uptown in SoHo. We’d have Fab 5 Freddy and Keith Haring together at a party, and all the clubs were named after candy bars. Hip hop parties would have skate ramps, with a great mix of poets, singers, rappers, and all sorts of young people on the same vibe.”

Williams’ mixed Japanese American and African-American heritage meshed well with this burgeoning culture, accepting of all races and combinations. “The founding partners of PNB were Jewish, Chinese-Jamaican, Puerto Rican, and Korean. Our backgrounds brought us a certain political consciousness, but we weren’t preachy—just all on a common wavelength.”

Some of Williams’ favorite memories of coming up in hip hop’s Golden Age include throwing runway shows with live dance troupes, staging events in elementary school auditoriums, and doing an epic graffiti wall inside Tokyo’s Club Asia, a collaboration with writers Bluster, Bru, Doze, and West. Today, Williams works as design director for American Rag, a clothing line for young men sold exclusively at Macy’s. “After 12 years of running PNB Nation with my business partners we all decided to move on to new things, but all of us stayed in the business and continue to travel the world developing new product,” he says. Considered one of the original entries in a field where longevity is key, PNB possessed what marketing teams and financial planners wish they could package, but find constantly elusive: street credibility combined with international notoriety and fashion industry respect.

“There’s so much sameness today in hip hop; the same with fashion,” Williams said. “But people will have to change. The current situation will get flipped, and people will change everything up.”

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage Vol. XVIII, no.1 (Spring 2006), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2006 National Japanese American Historical Society