How do we define "the way of the Nikkei"? As Japanese Americans assimilate into the wider society through intermarriage and migration, many community leaders have begun to question what constitutes the Nikkei identity and whether our community is disappearing due to lack of new Japanese immigration. Although I understand their concerns, I believe their worries are misplaced for several reasons.

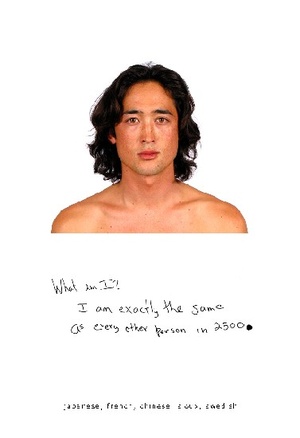

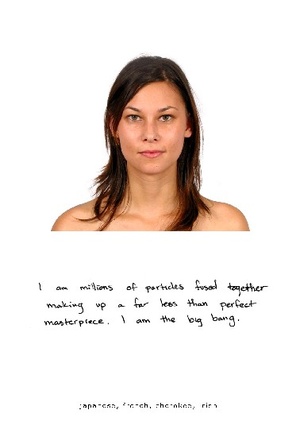

Nikkei identity is not limited to people with two Nikkei parents. Today, up to 90 percent of the Yonsei and Gosei, including all of my nephews and nieces, are "hapa" (half Asian Pacific American) or, as I prefer to call them, Hapanese Americans. Yet they are often more interested in their Nikkei heritage than their 100 percent Nikkei peers who take our culture for granted. Today, being Nikkei is a mindset and an attitude, not a question of blood, as the US government ruled in World War II. Young Nikkei can embrace, ignore or reject their Nikkei heritage as they wish. There is nothing inherently right or wrong about not choosing to be Nikkei, since a person may choose to identify with other cultures. Nikkei style is a question of personal style, of the mind and soul, and not of race.

Even "purebred" Nikkei are multicultural because of our diverse backgrounds. We view life as a buffet table, freely adopting the flavors of other cultures. For example, I grew up with Mexican Americans in San Jose and was often mistaken for being half Mexican because of my folded eyelids and dark suntan, even though all my ancestors are Japanese in origin. Most of my classmates were Latinos, so I naturally identified with them and felt "medio Latino" (half Latino), which led me to work in Venezuela, with Puerto Ricans on the East Coast and for a La Raza Unida political campaign in East Los Angeles. My Nikkei friends often wondered why I chose to be "half Latino," with its racial and class undertones, but I enjoyed the warmth, camaraderie, music and spontaneity of Latinos, who are a refreshing change of pace from the more staid, button-down seriousness of Japantown and my Nikkei peers. I could let my hair down and immerse myself in lively dances and Santana’s music.

Nikkei reflect their environments and communities. Los Angeles Nikkei are flashier and more segregated than San Francisco Nikkei, who tend to be more politically liberal, but socially conservative. San Jose Nikkei retain a "Meiji village" flavor because of their strong agricultural roots. When I studied back East during the late 1960s, I found East Coast Nikkei to be much more individualistic than my West Coast Nikkei friends, who was struck me as tight-knit and cautious. Why was this? In college, I discovered what they meant when they said: "The only Nikkei you’ll see is the one in the mirror in the morning." They explained that they were usually the only Nikkei around and had to rely on their wits; so Nikkei in the Midwest and East Coast are freer and more independent-minded than West Coast Nikkei because they cannot rely on a large community for support or identity.

The reality of their Thoreau-like isolation struck home when I spent my first holidays alone without a Nikkei soul around. Until then, I was part of the extended Tatsuno family and San Jose Japantown. Suddenly, I was a small fish forced to navigate a huge sea alone. It was sobering and lonely, and I longed for gohan and mochi-gashi. When I returned to the West Coast during summer vacation, I immediately gravitated to Japantown and the Obon festival to reconnect with friends and reassure myself that I had roots.

When I taught English as a Second Language in Okayama, Japan in 1973 to 1975, I felt vindicated by my Latin style. I met Brazilian Nisei exchange students who were friendly, open, and funny. They gestured wildly with their hands and strutted down the street as though they were dancing the samba. And they threw wild samba and bossa nova parties every weekend, which my Japanese friends loved! They were wilder than my Latino friends and I felt uptight in comparison. We would all dance in circles and hug each other, which I had never done with Nikkei in the states, and they would grab me to loosen me up. Surprisingly, even my Japanese friends were less inhibited than California Nikkei and laughed, joked and danced like the Brazilians. The Brazilian Nikkei reminded me of Hawaiian Nikkei who are so open, friendly, and warm. I immediately fell in love with the Brazilian Nikkei and felt I could be both Nikkei and fun-loving. The Aloha and Brazilian Nikkei styles are so much more spontaneous and relaxed, unlike the stiffer, more serious West Coast Nikkei.

It dawned on me that the West Coast close-to-the-vest seriousness was the result of being a harshly persecuted minority for a century. Unlike the Hawaiians and Sao Paolo Brazilians, who virtually control their economies, the West Coast Nikkei are a tiny minority at the mercy of the larger society. Except for the Latin American Japanese deported here secretly, we were the only ones interned in camps during the war. That’s why the Hawaiian GIs in the 442nd and 100th couldn’t understand the West Coast Nikkei until they walked into the stark detention camps under armed guard. Then they understood how it felt to be hated and a prisoner in one’s own country. No wonder mainland Nisei were serious "kotonks"; they had to gaman through indignities that the Hawaiians could not even imagine.

How did our experience on the mainland translate into Nikkei styles? First, white America in general tends to be very serious and judgmental because of its Puritan and Germanic origins and the powerful influence of the Protestant churches. In many church groups, such as the Methodists and Baptists, it was not proper to laugh, dance, and go to movies, which were viewed as the devil’s work. Even growing up in the Methodist Church in San Jose’s Japantown, we noticed the Buddhists seemed to have all the fun. They ate, drank, gambled and laughed more freely, while we felt guilty and sinful for even thinking of partying too much.

Second, the century of racial discrimination, the camps and the unwelcome treatment to returning internees kept Nikkei "in their place." Without political and legal protections, West Coast Nisei were afraid to stick out their necks. We Sansei were taught to keep our heads down, study hard and not rock the boat. Pursuing a profession was considered the passport to success. Life was harsh for troublemakers and slackers. If a Nikkei was caught committing a crime, it was big news in Japantown. Thus, we West Coast Nikkei worked hard and put on a serious demeanor to prove ourselves as 200 percent loyal Americans. The Brazilian Nisei struggled during the early 19th century, and although individuals were incarcerated, the population was not relocated en masse during WWII. When I spoke with my Brazilian Nisei friends, they seemed happy-go-lucky, did not fear speaking out frankly as did my West Coast Nikkei friends, nor did they feel an obligation to prove their loyalty as Brazilians. They often wondered why I seemed to try so hard to conform and be good. The camps meant nothing to them.

Fortunately, American society is opening up due to movements for increased civil rights, women’s liberation and gay rights, making it easier for West Coast Nikkei to live the way we please instead of fitting into the "Model Minority" stereotype. Yonsei and Gosei can be speedskaters like Apollo Ohno or gay filmmakers like Greg Araki. Nikkei styles are becoming more diverse, open, fluid and multicultural. Due to mingling and intermarriage, we Nikkei can choose our own styles. The best examples are the Hapanese Americans who consciously (and unconsciously) mix a variety of Nikkei, Afro-American, Latino, Asian, Caucasian and other cultures. They are the wave of the future.

For example, my nephew in San Jose is married to a Mexican American woman and enjoys both cultures, while my half-Caucasian nephew in Colorado competes in extreme skiing and snowboarding. Both show interest in Nikkei culture, but have forged multicultural lives of their own which are refreshing and unique. I envy them since they do not feel pressure to conform to the "good Nikkei professional" stereotype, but are freer to be themselves. They are at the cutting edge of our community and show the way to our future. However, many Hapanese feel like outsiders in the Nikkei community, which is still closed and tight-knit, so we all need to show much greater recognition and acceptance. Instead of marginalizing Hapanese, we should embrace them. After all, they are our children and grandchildren. Perhaps we need a Hapanese festival to celebrate their freshness and diverse styles. Let ten thousand blossoms bloom!

So what is Nikkei style? Today, it is everything and anything a Nikkei wishes it to be. We can tap into our Japanese and Nikkei heritages, mix them up with Latino or Arab cultures, and serve it up in dance, music, legal work or philosophy. Nikkei styles have become "fusion cultures" that reflect the latest in current culture and thinking. We are an absorptive community, a cultural chameleon that reflects its environs.

Amid this blossoming of Nikkei expression are common values and principles that we all share, whether in North or South America—hard work, education, perseverance, attention to detail, and pride in ownership. In a sense, we may not be all that different from other cultures, but one thing is certain: contemporary Nikkei styles are very fluid, cutting-edge and innovative, perhaps more fast-changing than many other cultures. In this global era, we need to better understand and inform ourselves of our changing Nikkei styles if we are to acknowledge Socrates’ dictum: Know thyself.

* This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage Vol. XVIII, no.1 (SPRING 2006), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2006 National Japanese American Historical Society