“...It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.”

-- From poem “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley (1849-1903)

Who has sacrificed any more to become Canadian than Japanese Canadians, particularly those who lost virtually everything during the World War 2 internment experience?

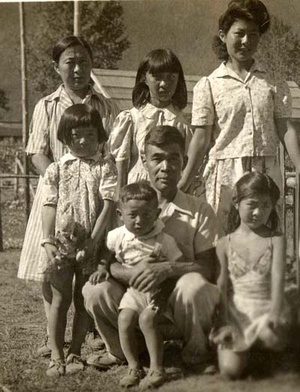

I suppose that most of our families have similar stories of loss and recovery. From time to time, I think of my grandparents who I remember as always smiling and positive and willing to sacrifice anything for my sake, which they really did for my parents when they were kids.

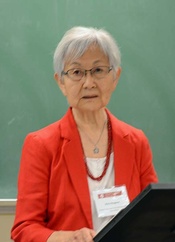

Mary Kitagawa - Speaking at the University of Victoria at the Inaugural Meeting of Asian Canadian Studies Network

When I read over the story of Keiko Mary Kitagawa (nee Murakami) yet again I am reminded about the campaign that she and her husband Tosh led a few years ago to put pressure on the University of British Columbia to award degrees to the 76 students that it had expelled in 1942 just because they were of Japanese descent. This was an act that is incomprehensible today, even amongst young university-aged Nikkei. It wasn’t until Mary and Tosh took up the fight (similar movements had been made at US universities), that this issue became known amongst Nikkei and the rest of Canadians. Justice was had on May 30, 2012 at UBC.

Similarly, she, Tosh and some other JC community leaders had led a campaign to rename a federal building in downtown Vancouver, Howard Charles Green, an unabashed ‘Jap-hating’ politician who was a leader in the movement to destroy the lives of 22,000 innocent JCs during World War Two. After a year of appeals, the building at 401 Burrard Street was subsequently renamed the Douglas Jung Building. Righting historical wrongs is an ongoing battle.

The following is part of Mary’s remarkable story which tells a part of all of our stories too. Her’s began more than 100 years ago when many of our descendants first came to Canada. It is a journey of self discovery, tenacity and, ultimately, one of forgiveness since it was having that capacity that allowed our community to forgive the government for its treatment of us during World War Two allowing us to move on, rebuild our lives in postwar Canada and to prevail over the bigotry and racism that did not diminish us or scare us away.

* * * *

“My father Katsuyori Murakami was born in Hiroshima, Japan. He came from a very privileged family. His father’s lineage began from the seventh son of the sixty-second Emperor, Murakami Tenno. The family owned very large tracts of land that were tilled by hired hands. His father never worked a day in his life. The household chores were done by maids and servants.

His mother, Mun Kashiwahara, came from samurai lineage. My father learned to play the piano and the violin very well. He was a very dignified man; physically and how he treated others. When he came to Canada as a sponsored immigrant in 1927 after he married my mother, he willed himself to learn how to farm, build greenhouses, and build homes. This was an amazing feat since he knew very little about performing any physical labour. He was an amazingly strong but gentle person, wise, generous, compassionate and hard working.

My mother Kimiko Okano Murakami was the first Japanese Canadian baby born in Steveston, BC. Her parents Kumanosuke and Riyo Okano came to Canada in 1896 from Hiroshima, Japan and worked in the fishing industry.

Success enabled them to own five boats. They sold four in 1919 and bought 50 acres of land on Salt Spring Island, BC. Later their land holding grew to 200 acres; water front, lush valley and virgin timber forest. Their successful farm was composed of many varieties of berries, large green houses for growing tomatoes and a section for growing vegetables.

In order to help with the labour, they sponsored several Japanese men from Japan to work for them. They were very community minded and contributed to the building of a school and church. During the Depression many destitute people came to their doorstep to be given food and clothing.

In 1939, they allowed two Japanese Canadian families from other parts of BC to build homes on their land. My grandparents were retired for several years when the Pacific war began and were living in a beautiful two-level home and enjoying life. That all changed when they were forced to endure the degrading conditions of Hastings Park and being sent to Magrath, Alberta to work on a sugar beet farm. The physical labour and brutal living conditions taxed their aging bodies. My grandfather died just a few months after he was given the franchise and freedom of movement anywhere in Canada on April 1, 1949.

We lived on a pristine 17-acre farm carved out of a forest. Our parents grew asparagus, a variety of berries, vegetables and had 5000 egg laying hen. Mother hatched every chicken from the egg stage in an electric incubator. We lived in an immaculate home that was built by my father.

Our parents hired Japanese women from Vancouver Island during the harvest and babysitters to look after the children. The Japanese women brought their children and they lived in a bunkhouse my parents provided for them. They ate with us; the meals were cooked by my mother who had countless other tasks to perform on the farm. She sewed all of our clothes and knitted all of our sweaters. If you want to know more about our mother, please Google, Kimiko Okano Murakami.

My parents were a powerful team. They took on challenges always believing that they would succeed. Failure was not an option. They were encouraging and future oriented; university was the goal they had for all of their children. Hard work without complaint was their mantra. They felt that strength of character can only be achieved through dealing with problems that we face. By example they taught us how to persevere through any challenges that we faced. They were our role models who taught us never to quietly accept the cruel onslaught of racial hatred, never to act as victims and always show a proud face to the world, never a face of defeat. They showed us how to be generous and compassionate toward others. They provided security and created opportunities for us. They believed strongly in education and allowed four of us to go to university.

Throughout their lives they were truly honourable and loyal citizens of Canada. With dignity and courage our parents brought us safely through some terrible, terrible times in our journey through life and ensured that our family prevailed.

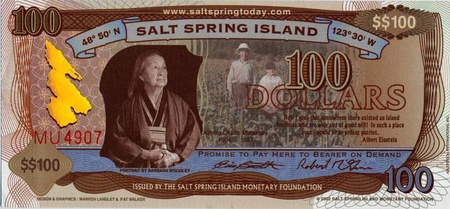

This portrait of my mother is the one that hangs in the permanent collection in the Archives in Ottawa.

My mother’s portrait by photographer Barbara Woodley hangs in the permanent collection in the Archives in Ottawa. That portrait is on the hundred dollar bill of the Salt Spring Island currency. On the reverse is a painting by renowned painter, Robert Bateman. Other denominations are one, five, ten, twenty and fifty dollar bills. Canada Central Bank has recognized the Salt Spring dollars as a “unique Community Currency”.

Coin World stated that the hundred dollar note is the first in North America to feature a portrait of a person of Asian ethnicity. Mother’s portrait was also featured in the prestigious McMichael’s gallery in Toronto, Ontario.

On March 17, 1942, father was literally dragged away from us by an RCMP officer who came to arrest him. It was a frightening event in our lives as we watched our father disappear into a void. Our minds were racing with dread wondering if he was being taken away to be shot. My mother remained strong for us as we awaited instructions by the Custodian of Enemy Property to vacate our beloved home. There was excruciating sadness and pain as we said goodbye to our beloved horse ‘Babe’, our adored pregnant dog ‘Mune’ and the 5000 chickens.

With our meager carry-on suitcases that we were allowed to take, we vacated our eerily silent property that was once alive with activities and happy voices. My mother’s journey into hell with her five children in tow began as we boarded the ship ‘Princess Mary’ at the Ganges wharf and was taken to the barns in Hastings Park. The shock of being forced to live in filthy conditions in a place just vacated by animals was overwhelming. For us who were accustomed to cleanliness and privacy of our own home, being herded together with thousands of other inmates was unbearable. The smell of urine and feces choked our lungs and permeated our skin, hair and clothing. Mother had to deal with a lack of facilities for her year old son, unpalatable food, lack of proper toilets and bathing facility. After several weeks we left this degrading condition and found ourselves on an old train to Greenwood. There we found out that our father was alive and working in the prison work camp in Yellowhead Pass with many Japanese Nationals.

We were reunited with him in Magrath, Alberta in July to live in a 10’ x 15’ shack that had no cooking or sleeping facilities. Mother fed us mostly from cans because she did not have a stove. Our water supply was from a pond where the cows and horses drank. My father worked for the farmer who thought of us criminals and treated us as such. After two months, my parents knew that if we stayed there any longer, we would all die. We contacted the Commissioner in Lethbridge who came to see our situation.

He decided immediately to move us to one of the “camps”. Accompanied by an RCMP officer we were transported to Popoff, BC (in interior British Columbia close to Slocan and Lemon Creek internment camps) for a short while, then to Bay Farm. After the snow came, we were moved into a tent in Slocan where we stayed until January 1, 1943. We were then sent to Rosebery, a newly created camp of unfinished 14’ x 28’ shacks.

Living conditions that winter were brutal. It was during one of the coldest winters in BC where everyone there lived in a structure akin to a basket. Keeping it warm was a challenge and the other non-facilities made daily living very difficult. We lived there until the Second Uprooting when we were given an ultimatum; go east of the Rockies or be deported to war torn Japan.

My parents had no intentions of going to Japan. They felt in their hearts that the Canadian government will one day come to its senses and give us back our freedom.

We were moved to New Denver, BC with all the other families that chose to remain in Canada. Even after Japan’s defeat, we were kept there for over a year. Reluctantly we went back to the dreaded sugar beet field in Magrath, Alberta, where we struggled to survive. Our oldest sister who had graduated from high school in New Denver found a job at a grocery store. Her income was crucial to our survival since the government had emptied our bank account. She wanted to go to university to become a journalist but was denied because we were destitute.

From Magrath we went to Cardston, just thirty miles south of Magrath to run a restaurant started by my grandfather and uncle. There my parents worked a double shift to make it a success. After five years, we had accumulated enough money to return to Salt Spring Island in 1954, five years after we achieved freedom.

We bought a house and five and half acre property to begin again our lives on the Island. The virulent racism that greeted our return was frightening.

Although we faced many physical threats from the RCMP, general public and Islands Trust, my parents held their resolve to not to allow evil to hound them off the Island. Their struggle for the right to live and earn a living where they chose to live continued for many decades. Although it is not quite so overt, our family still struggle against hate and racism on Salt Spring Island.

My sisters, Alice, Violet and I attended school on Salt Spring Island until December 1941. We did not have any schooling until we reached Rosebery incarceration camp in 1943. Alice with other students her age walked five mile to New Denver to attend a United Church sponsored high school. They were taught by wonderful Caucasian missionaries through correspondence. Although the elementary students were taught by newly trained Japanese Canadian high school graduates, I do not remember much about what they taught us. School rooms were shacks that were converted to accommodate classes.

It was a challenging situation for the young teachers who did their best for us. After leaving New Denver in 1946, we attended regular school in Magrath, Alberta while our parents laboured in the sugar beet fields. There were only a few Japanese Canadian students in our school so we socialized mostly with the white children. When we moved to Cardston, we were the only non-white students in the schools.

After the initial shock of being labeled as “Japs”, we were accepted by the people of the community and students. I graduated from the high school in Cardston and moved with the family back to Salt Spring Island in 1954 where I spent a year, helping my parents clear the land and prepare the farm. I left for Toronto the next year to attend Trinity College at the University of Toronto. In order to manage my meager finances, I worked for my room and board. I graduated in 1959 and enrolled at UBC to attain my secondary school teaching credential.

It was easy to obtain a teaching position in BC at that time except on Salt Spring Island. I wanted to teach there but when I applied, the school board told me that “no Jap was going to teach their children”. Luckily for me, Kitsilano Secondary School (in Vancouver) welcomed me. I taught there for only three years during which time Tosh and I were married.

We left Vancouver for Richmond, BC soon after our son was born. Two years later, our daughter was born and we moved to Tsawwassen where we have lived for forty six years. When our children were of school age, I became a substitute teacher for the Delta school district. After the children graduated from high school, I retired to pursue other interests.

© 2014 Norm Ibuki