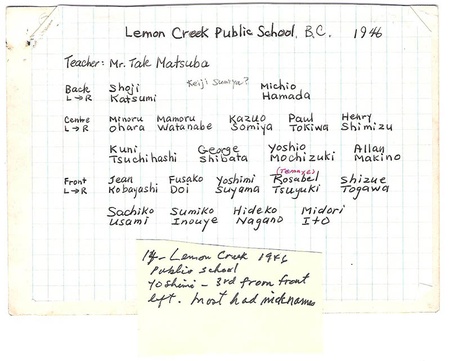

“In the 1945-1946 school year, Miss Haruko Ito taught us grade 7, but she left us before the end of the term. Tak Matsuba became our new teacher and continued on until June 1946. (We were exiled to Japan the same year!) He taught us to do our best in good faith and to complete our given tasks willingly. I remember him as a pleasant, fair person who was highly respected.”

- Nisei Susan Maikawa recalling school life in Lemon Creek internment camp

When I first went to Japan to teach English in 1995, Lloyd Kumagai, a Canadian Nisei, was the first person to track me down by phone at the Maruzen bookstore in Sendai to offer his assistance and to befriend me during those first weeks.

Now, I forget exactly when I first met Tak Matsuba, 87, another Canadian Nisei, but when I moved to Ibogun in Hyogo-ken, Tak and Tom, another Nisei, were the first ones to invite me to have dinner. Afterwards, we’d visit ex-pat, Gen Hamada’s ‘Owl’s Nest’ bar in Osaka for a few drinks. (BTW, Tak’s brother, Takumi, was the owner of the former “Bushi-Tei” restaurant in San Francisco.)

After the internment camps were closed, Gen’s parents “relocated” to rural Ontario, west of Brampton, close to the Naka greenhouse and farm and not far from where I grew up. Gen, by the way, went to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, was a pretty good junior hockey player and a high school gym teacher before heading over to Japan where he settled in the 1970s.

It wasn’t until I first went to B.C. and Japan myself that I became connected to these scattered remnants of the post-WW2 JC community, which, 20 years ago were a lot more evident. No, we’ll never have J-towns ever again but the friendships and connections need to be preserved.

If there is one reason to justify the preservation of our cultural centres it is to provide places for us to get together, befriend and get to know one another. Now, more than ever, we need to create these opportunities to celebrate who and what we are and where we come from.

So, why is it important for readers to share their own stories?

If you don’t then the remarkable narrative of how our forefathers came from Japan and the trials and tribulations that they (and you) endured to become Canadians will become lost for future generations, including your grandchildren who will then never really know who you are.

So, Tak, can we begin with some background about your family? Where are they from in Japan? Where were they in BC before the internment?

My dad was from Mio, Wakayama-ken, and mom was from Fujii also in Wakayama. Before “THE WAR” (Tak’s capitalization), we lived in Vancouver at 151 East Cordova Street where dad had a small grocery and dry goods store inherited from his father.

And your mother?

Mom was a full time housewife.

Our family goes back a long ways in B.C. As a child, I faintly recall some Issei telling me, “When your grandfather came to Canada, the city hall of Vancouver was still a tent.”

Where did you go to school?

I lived and went to school in Vancouver. I went to Strathcona School for my elementary school and then went to Fairview Commerce and when the War started I was transferred to Grandview Commerce. During this time, I also attended the Japanese Language School in Vancouver. My education was interrupted due to the war and the forced evacuation of Japanese Canadians from the B.C. coast. Our family was sent directly to Lemon Creek (internment camp) without a stay at Hastings Park.

What was it like to be Japanese Canadian before WW2?

Like most kids of that time, my life outside of school prior to WW2 was centered around Powell Grounds playing baseball, softball and/or soccer. I also played basketball at the United Church gym.

What were your dreams and aspirations before internment?

I am trying to recall if I had any dreams or aspirations at that time. It is so long ago. I was still in my early teens that most likely I was more keenly interested in going out and “playing” with friends than anything else. In fact, when Pearl Harbour was bombed, it was a Sunday and I was with friends out on Powell Street on our way home from playing badminton at the Japanese Language School when we heard the news on the radio. (The news came from a radio in a parked car.) It had a very sobering effect on all of us.

What was it like for your parents to have their property taken away and sent to Lemon Creek?

It must have been devastating to lose almost everything they had worked all their lives to achieve, but in retrospect, they didn’t show it too much. Being born in the Meiji Era, they had that stoicism of “gaman” and “shikataganai” that they seemed to accept almost whatever came along.

How did the internment experience affect how you thought about being Canadian and Japanese Canadian?

Everybody in the internment camp was Japanese and I thought of myself as Japanese and that is why I am in the internment camp. There is a contradiction here. While I thought of myself as Japanese, there was also the feeling why did the government treat us Canadians the way they did?

The explanation probably lies somewhere where, as Japanese Canadians of that era, we suffered so much discrimination that we were never allowed to forget that we were of Japanese racial origin.

Nowadays, when people talk about multi-cultural Canada, I sometimes tell them that I am a product of pre-multicultural Canada!

Why did your family decide to go to Japan after WW2?

Dad had lost almost everything he owned in Canada, and to leave Lemon Creek to go East meant starting from scratch whereas in going to Japan, he at least had a house he owned. We were a close knit family and what dad decided we accepted. Dad was a naturalized Canadian and I think he felt that he had enough and that if he returned to Japan, he would be accepted in addition to still owning a house.

Where did you go and what were conditions like there?

We went to Mio in Wakayama where as I stated earlier, dad had a house. Conditions were pretty rough. Heating was bad, no sewage system, water came from a well. I thought that there had been no progress then than fifty years before. Of course years later, progress was very rapid, but this was mostly in the larger cities and progress was slower in the countryside.

How accepting were the Japanese locals?

In Mio, most households had family or relatives who had immigrated to Canada that the locals accepted “returnees.” I think there was some feeling of envy on the part of locals because what little we had brought from Canada was still very desirable for locals who had less. However, I only stayed about a month in Mio, so really didn’t have much contact with the locals in Mio.

Did the Japanese see you as one of them or Canadian?

When I was hired by the Occupation Forces, there were a number of American Nisei in a similar situation and our work at the office was with military personnel that we were seen as Canadian/American or foreigner by the locals.

© 2014 Norm Ibuki