There was a bowling alley called Triangle Bowling Alley located at Beverly and Atlantic Blvd. in East Los Angeles (East Los) before it burnt down in the ’80s.

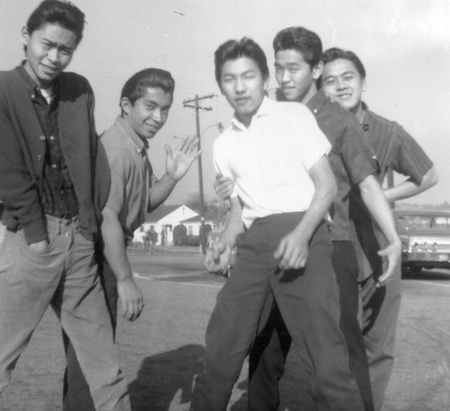

It was in the early ’60s that several boys from Garfield High School congregated there after school to shoot pool, gamble, bowl, and shoot the sh**—many were Buddha Heads (Japanese Americans). We are not talking about the stereotypical well disciplined JAs that received straight As in school here—most of those didn’t go to bowling alleys. These JAs from Triangle Bowl mixed well with all of the visitors to the place who came from Roosevelt High School, ELA College, and anywhere else for that matter.

These JAs chose to hang with the chicanos (hispanics) that they grew up with but for the most part, they didn’t mimic the cholo (chicano gangster or pachuco—of old) pocho speak or syntax. They also chose not to hang with the Weros (slang for Anglos). Very few, joined their local Chicano gangs nor were they invited to. Also in those days there were few bloods (black slang for blacks) attending Garfield High School to mimic—besides the bloods weren’t respected by the Chicanos.

In the late ’50s, near Triangle, a few young JAs from Kern Jr. High School who wore cool trench coat length wool jackets like those worn by the bloods on the westside of town were called out (to fight) as they walked through a park by a gang who claimed that “turf” as theirs—Westside cool be damned, no more jackets.

Instead of integrating into the Chicano culture, the JAs from Garfield were able to talk like Anglos as they were taught in school—which helped them steer clear of confrontations with the cholos. Though the JAs from Roosevelt were more apt to talk and dress like the bloods because there were more there—many bloods came from Pico Gardens and Aliso Village Housing Projects.

The JAs of East Los were respected by the Chicanos who were their friends and there wasn’t much pressure for them to join the Chicano gangs—and again for the most part they didn’t. Although, they dressed like their Chicano camaradas (homies), in order to blend in. The wearing of starched, pressed khakis or Levis with Sir Guy or Pendelton shirts was in vogue. Spit shined combat boots, French toe shoes, and Romeo slippers were also the popular kicks then. Most were able to talk like a cholo, on demand—if there was a need to—like “odale”. On the other hand, the JAs favored different hairstyles (do) than the chicanos—like the waterfall, Trojan flat top, or pompadour—the chicano would just comb theirs straight back. Also, when a JA would get into a fight, his cholo friends would back (fight for) him. If the fight was between two JAs from different barrios (neighborhoods), then the respective chicano gangs could be called upon for backing (fighting reserve).

In the early ’60s there was a fight in Boyle Heights near the then International Institute (now Kiero), between the Devastators, a predominately JA gang from Roosevelt High and some of the JAs from The West Side (Crenshaw area) and their blood backing. There was a one-on-one fistfight in the street by the JA leaders from each side and the one from the Westside won. One of the Westside backers, a blood, was later hit with a tire iron across the head by a Devastator JA—call it a draw. This confrontation was over quickly and didn’t become a war.

The JAs from East Los went to the dances and carnivals all over Los Angeles unmolested and without molesting—this included J-Flats, University, Venice, Sawtelle, WLA (Santa Monica), Los Feliz, Gardena, Long Beach, The Valley, and even the Westside. It was all about seeing the city and girls, but not necessarily in that order. The JAs from all of these areas, including some from the Westside, freely visited Triangle Bowl—they liked the pills and marijuana (drugs) that were available there. They, though, wisely stayed away from the cholos. Among those that were welcomed were several JAs and a couple of bloods from the Westside who went to Mount Vernon Jr. High School and later Dorsey High. They weren’t members of the gang—instead were in a car club called the Royal Coachmen and at least one JA transferred to Garfield High School, after being kicked out of Dorsey and was well received by the chicanos.

Later in the mid ’60s a few of the JAs that hung out at Triangle Bowl, first met several other JAs at the Senshin Carnival on the Westside, and they thought that they may have a fight, when they were outnumbered. These JAs from Triangle noted that these other JAs were acting belligerent and that some were loaded. Who were these bad dudes (Yogores) from the Westside? They would find out that they were the Prime Ministers, a gang that were a subset of an older gang called the Gents. Soon after, these Triangle Bowl JAs and their other JA and chicano friends, also from Triangle Bowl went to Midtown Bowl to confront the Ministers and to secure respect. A Chicano leader from the Ministers begins to get acquainted with the boys from Triangle Bowl in an apparent attempt to diffuse the situation—shucking (banter) and handshaking (grip). But another leader, a JA, from the Ministers objects and accosts one of the visitors and a one-on-one fist fight erupts—resulting in the JA from Triangle winning. It is presumed that the Ministers would be looking for revenge for it was known that the Ministers say that they never forget.

That revenge would soon happen at the Nisei Relays, a part of the Nisei Week festivities, held at Dorsey High School, where many of the Ministers used to go to school. The same JA from Triangle Bowl that fought earlier got jumped by several Ministers. It was said that there were a couple of hundred Ministers and their backing across the Westside—so the challenge for these few boys from Triangle Bowl was enormous if revenge was to be effected for this jumping. As it turned out, there were only a couple of dozen of the 200+ at any event, even less were the ones that were willing to fight, and even less—the ones that did.

Soon thereafter, some other JAs from around LA and some of the Buddha Bandits from J-Flats visited Triangle Bowl with tales of also being harassed by this gang called the Ministers from Dorsey and LA High in the Crenshaw area of the West Side. The Ministers talked the talk and walked the walk of the bloods that they mimicked, they were even better at it than the bloods. Then other JAs from all over Los Angeles with their tales of woe attributed to the Ministers, started to drive great distances to hang out at the Triangle Bowl—perhaps because it became known that the boys from Triangle Bowl stood up to the Ministers. The Bowl was becoming a sanctuary for JAs harassed by this gang. Stories of their miseries were shared in a communal spirit at the Bowl and now with this common enemy, a coalition was formed called East Side. Most of those boys previously from Garfield High would organize many of the East Side skirmishes against the Ministers.

When the Ministers called Triangle Bowl and not knowing whom to ask for, they would ask for the Triangle Boys to be paged to the phone—and thus they were named. These phone calls to the Triangle Boys were sh** talk (attempts to intimidate) and the only communication that the Ministers would have with the East Side between fights—they talked the talk during these calls. The Triangle Boys and East Side on the other hand would walk the talk.

It should be noted here that there were established Chicano gangs in the barrio around Triangle Bowl and that if the Triangle Boys were to consider themselves a gang—they would have to answer to the wrath of those gangs. The Triangle Boys instead drew from their barrio for backing and those cholos and vato locos (crazies) who considered that these Triangle Boys were on a temporary mission and thus not a rival. Some of the younger brothers of the Triangle Boys would form their own cliques like F-Troop and also joined East Side in the war.

Most of the now Triangle Boys were JAs, but there were several Chicanos and in all there were only 12 or so at any time. The Triangle Boys hung, carpooled, played pool, gambled, drank, organized, and fought together—normal for them. They were the hosts to their newfound comrades and through networking, organized much of the gang banging.

Displaced JAs from around the town would congregate at Triangle to find out “what’s happenin”. With the agenda established the caravan of cars would set out to the West Side for the night’s activities—in larger numbers—to seek and destroy. There were East Side guerillas that would attack the Ministers on their own without physically checking in to Triangle Bowl and spontaneous attacks were encouraged. Still others would keep in touch with Triangle by phone and drive out to the events directly from their pads. These JAs and their Chicano friends were a part of East Side but didn’t consider themselves Triangle Boys. Many of these JAs were already affiliated with their Chicano friends in their own barrios, were therefore already established and were content to be a part of East Side only for the duration.

As mentioned before, the JAs had loyal Chicano friends or knew of other Chicanos who liked to fight. The JAs from Boyle Heights drew their backing from a Chicano gang called Little East Side and another gang from the Belmont District called Loma. The Triangle Boys drew backing from various chicano gangs in Mara Villa like El Hoyo and La Lomita. But many of the Chicanos in East Side were not members of gangs although they sought adventure and the JAs would provide transportation—have gun will travel.

From a Minister’s perspective one can understand why they chose to believe that they were being sent to the hospital by the Esse’s (Minister slang for chicanos), for the Esse’s had a propensity for stabbing and carrying guns. This wasn’t always the case, for there were also some bad JAs from East Side including some from the Triangle Boys that did much of the fighting—not just the Esse’s. Surprisingly there wasn’t the same energy delivered by the bloods who backed the Ministers for they were regularly “catching hat” (leaving the fold).

The cry, “East Side!” (ala “Viva Zapata!”) could be heard at Hody’s Drive-In Diner, Mid Town Bowl, Holiday Bowl, Roger Young Auditorium, Park Place Auditorium, Crenshaw Auditorium, Old Dixie, Surf Riders, Nisei Week Carnival, Saint Mary’s Carnival. In the retaliation, there was one visit (raid) to Triangle Bowl by several Ministers that ended almost in a fistfight between a JA representative from the Ministers and another (mentioned earlier) from the Triangle Boys—both retreated.

Later that month though, some of the Ministers shot up the Triangle Bowl building from across the street in the wee hours of one morning and were promptly arrested by the East Los Angeles Sheriffs—no more visits. In contrast East Side would raid Mid Town Bowl week after week until they couldn’t find any more Ministers. Then the raids moved on to Holiday Bowl where the Ministers sought sanctuary. At Holiday Bowl during one raid, Ministers were seen holding the door closed to prevent East Side’s entry to no avail. The Triangle Boys threw B-B coated cherry bombs at them and their cars as they departed. East Side would wait in prey at Hody’s Drive-In Diner, a popular late-night Ministers haven, and would accost them and their cars with 55 gallon trash cans and broken ketchup bottles to the face—this activity also discouraged other patrons from returning.

East Side also stabbed an Algonquin (basketball team?), multiple times (revenge), when a fight broke out at Roger Young Auditorium after the dance there. At another dance at Old Dixie, East Side stood up to the Ministers and Algonquins and threw newspaper vending machines at their cars before they sped off. Eventually it became hard to find Ministers or their newfound older Algonquin backers—a few could only be found in Gardena. In Gardena in the waning days of the war, the Triangle Boys knocked unconscious a Minister who was brandishing a gun and intimidating a house party there. The gun was confiscated and was brandished there after by one of the Chicanos in the Triangle Boys at other social events. It is said that some Ministers left the neighborhood, others the state, and still other Ministers became evangelistic and formed the Yellow Brotherhood. The Ministers started to forget.

By the mid to late ’60s things were becoming serene as they were before the Ministers… There never was to be a Triangle Boys II or III—for when the mission was over no other group of young JAs at Triangle Bowl chose to create them—out of respect. JAs from everywhere and their friends again traveled freely, except for those that got drafted, enlisted in the Armed Services, or got married to the girls they were looking for in the first place—at least for awhile… In retrospect these activities and fights were tame compared to the mayhem we live in today, but then again, that was all that it took—adventure.

© 2014 Earnest Yutaka Masumoto