One thing was clear to businessman Frank Kawana when he took over his father’s Little Tokyo kamaboko business in 1955: people were not clamoring for fishcake. Quite the opposite—once a Japanese American staple, kamaboko sales were declining in the U.S. Like his father Otoichi Kawana, Frank somehow could not abandon what he secretly hated as a “smelly business.” At his mother Kume’s pleading, he reluctantly joined the family enterprise. While working to keep the company alive, he did something few people in this country have managed to do: he discovered and sold a revolutionary new product to the American public—imitation crab. By so doing, he turned his family business—Yamasa Kamaboko—into a major food enterprise.

Now known as the “Father of Surimi,” Frank has learned many valuable lessons on his journey to the pot of gold at the end of the pink-and-white rainbow. He would not make his father’s mistake of not doing his homework. His Issei father chose Los Angeles to make kamaboko without knowing there were eight competing kamaboko shops in Little Tokyo in 1938. Frank would also get to know his customers, remembering as an enterprising young boy at Rohwer, he started a shoeshine business only to find out that his first (and only) customer’s shoes were brown—and the only polish he had was black.

There were other not-so-amusing lessons learned along the way, but Frank undoubtedly inherited the entrepreneurial gene from his father, Otoichi Kawana tried his hand at everything from farming to the restaurant business to working for Ford Motor Company before stumbling onto the kamaboko trade when he met George Hosaki in Vancouver. Already a successful businessman, Hosaki shared his know-how and equipment with the Kawana family, and even drove them to Los Angeles from Seattle in his Cadillac. Once settled on Seventh Street, the Kawanas operated Yamasa Kamaboko (named after Hosaki’s company, Yamasan) next to a Japanese-owned restaurant, barbershop, and grocery store. Even though there were potentially 35,000 Japanese American customers in the three-mile radius around today’s Little Tokyo, it was a tough time for the burgeoning business.

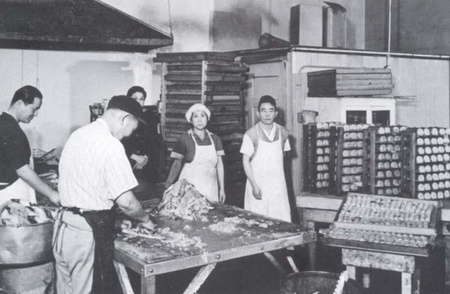

Like other Japanese owned business in Little Tokyo, the Kawanas closed shop when the war forced them into camp in 1942. Leaving their equipment behind in a garage, then were sent to Santa Anita and then to Rohwer, Arkansas. They were able to reclaim it when returning to Little Tokyo in 1945, and Otoichi made the dubious decision to open up again on Second Street beneath the old Alan Hotel. The family lived behind a commercial storefront six doors down, and Frank remembers working long hours in the odoriferous shop “without child labor laws” to protect him. Kamaboko-making was still a rudimentary handmade process that included scraping the fish, washing the flesh until all the oil, blood, and odor was removed, and forming it into a paste. Modern machinery would not arrive until the late 1950s.

After the war, Frank found himself growing up in a Japanese American community big enough to serve 600 customers on his Rafu Shimpo paper route. The eager young entrepreneur soon monopolized the newspaper delivery business by expanding to include both the Shin Nichi Bei and the Town Crier.

Also working making kamaboko alongside his mother and father on holidays and weekends, Frank happily turned to a cleaner business after graduating from Belmont High School. Together with a friend his father met during the war, his family invested in a jewelry store, Ten Shin Do, on San Pedro Street between First and Second, and Frank learned the watch-making trade. As fate would have it, his career as a watchmaker was cut short when Frank was drafted to serve in the Korean War.

While Frank was serving in Japan, his father became gravely ill and unexpectedly died. The son who grew up in the kamaboko business was asked to return from active duty to help run things. Frank was reluctant to go back to a business that held bad childhood memories and did not hold much promise, but did so at his mother’s insistence.

After the Korean War, Frank took over Yamasa Kamaboko and moved the operation to Stanford Avenue (where the business operates today). One goal was clear, remembering the many times his father would try and fail to come up with an idea what would attract a bigger market for kamaboko, he was determined to keep his father’s dream alive. But he had still not learned the most important lesson of all—timing. He tried making products based on surimi (the basic fish paste material of kamaboko), such as baloney, salami, and sausage, under the fanciful names of Sealoni, Sealami and Seasage. It was not long before he realized that America was not ready for seafood-based product. In the 1960s, fish was something that most Americans mandatorily ate on Fridays, at a time when pizza and hot dogs were cheaper and tastier. Billy the Cod was no match for Oscar Meyer.

It was another twenty years before Frank hit the surimi jackpot. “The Alaskan king fishermen had almost depleted the crab fields, and so the king crab that used to cost three to four dollars a pound went up to fifteen to twenty dollars,” Frank recalls. He had seen imitation crab made from surimi when in Japan, and figured it was time to introduce it to the U.S. market. Together with a Japanese partner and new custom machinery, Frank formed JAC Creative Foods and began producing imitation crab for two dollars a pound. At about the same time, the now ubiquitous California roll first hit the sushi bars of Little Tokyo. The rest is surimi history.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Frank Kawana has always sought the next business challenge. After starting out in the shoeshine business, newspaper delivery, and watch trade, Frank went on to dabble (with varying degrees of success) in the hotel business, a food brokerage company, vending machines, travel agency, pineapple importing and packaging, noodle making, and a machine shop. A partnership with his friend Ken Osaki yielded the Tengu brand, which Frank named after the Japanese fable. Tengu struggled for years trying to sell gyoza and shiu mai, and Frank simply could not wait it out and withdrew before Osaki created the best-selling beef jerky for which Tengu is known today.

Beyond his own business ventures, Frank prides himself on having recruited his wife Sachie and sons to follow in his footsteps. His eldest son Teiji, an attorney, runs JSL Foods, a company that manufactures everything from yakisoba to almond cookies, along with son Koji, who also managed Yamasa for ten years. A former architect, Frank’s youngest son Yuji has been general manager of Yamasa for the past thirteen years. Frank claims he also “created a monster” in his wife Sachie, who after raising their three sons has become the pillar of Yamasa Kamaboko and now “refuses to retire.”

In between reporting to JSL Foods and Yamasa Kamaboko, Frank still spends his days dreaming about the future. He wants others to share in his success by teaching them a little of what he has learned along the way. Besides providing practical training and help in starting new businesses, he hopes to help young Nikkei develop the confidence that he learned the hard way. Thankfully, his success has given him first-rate credentials. “You must have an unreachable goal or dream, and even if you fall short, it’s still a hell of a way from where you were!” teaches Frank. Another Frank-ism—“The difference between success and failure—or being considered a genius or idiot—is paper-thin.”

Frank Kawana is no doubt considered a genius by peers in the food industry. But according to this genius, he could easily have been known as a world-class idiot were it not for his father’s dream, perseverance, luck, and—yes—timing.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices (2004) by the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2004 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California