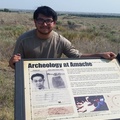

It’s been mentioned before: the Granada War Relocation Authority Center in Colorado, one of ten such WWII American concentrations camps scattered throughout the U.S.A., was given a name change to Amache. The name change was to avoid the confusion of having two U.S. Post Offices within a mile-and-a-half of each other with the same name. One was the nearby town of Granada; the other was the Granada WRA camp. It was a practical decision, but it turned out to provide a bit of irony that our camp was given the name of a Native American, Amache.

Ironic in that both the Native Americans like the Japanese in America were evacuated from their homes and relocated by the U.S. government in their time in history without due legal process. Also, discovering a bit of related Native American history directly related to our camp’s namesake, “Amache” made this telling, more compelling.

Amache was the daughter of Cheyenne Indian Chief Ochinee (One-Eye). In 1862-63, Amache was courted by and married John W. Prowers (1839-1884), prominent cattle rancher for whom the Prowers County was later named and where our concentration camp was built in 1942 to hold up to 7,500 Japanese prisoners in Colorado during World War II.

Amache, the concentration camp located near Granada was in the Great Plains of America, ancestral and then current homeland of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, who use to hunt buffalo and pitch their teepees in this same region. The whole of North America, as well as South America, today’s Canada and Alaska were inhabited by a thriving nation of different Native people for centuries before European explorers began to arrive.

To appreciate and respect the long-established history of the Indians in the Americas, one should read 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus by Charles C. Mann.

In this groundbreaking work of science, history, and archaeology, Charles C. Mann radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus in 1492.

Contrary to what so many Americans learn in school, the pre-Columbian Indians were not sparsely settled in a pristine wilderness; rather, there were huge numbers of Indians who actively molded and influenced the land around them. The astonishing Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had running water and immaculately clean streets, and was larger than any contemporary European city. Mexican cultures created corn in a specialized breeding process that it has been called man’s first feat of genetic engineering. Indeed, Indians were not living lightly on the land but were landscaping and manipulating their world in ways that we are only now beginning to understand. Challenging and surprising, this a transformative new look at a rich and fascinating world we only thought we knew.—Amazon.com book review

Like for the Native Americans, we Japanese in America were targeted victims of racism, economic greed, unfounded fears, and politics.

During the 19th century, the ideology of manifest destiny became integral to the American nationalist movement. Expansion of European-American populations to the west after the American Revolution resulted in increasing pressure on Native American lands, warfare between the groups, and rising tensions.

As American expansion reached into the West, settler and miner migrants came into increasing conflict with the Great Basin, Great Plains, and other Western tribes. These were complex nomadic cultures based on (introduced) horse culture and seasonal bison hunting. They carried out resistance against American incursion in the decades after the completion of the Civil War and the Transcontinental Railroad in a series of Indian Wars, which were frequent up until the 1890s but continued into the 20th century. Over time, the United States forced a series of treaties and land cessions by the tribes and established reservations for them in many western states. U.S. agents encouraged Native Americans to adopt European-style farming and similar pursuits, but European-American agricultural technology of the time was inadequate for often dry reservation lands.

—“Native Americans in the United States,” Wikipedia

Simply put, the Indians were being moved around to different locations and reservations for the simple fact that they got in the way of the expansionist invaders. Treaties were made to deed reservation land to the relocated tribes, but when gold or oil was discovered on those lands or railroads needed to be built through them, the treaties were broken and then the Indians were forced to move yet again.

To put a timeline perspective on this period, the American Civil War, 1861-1864, was still raging.

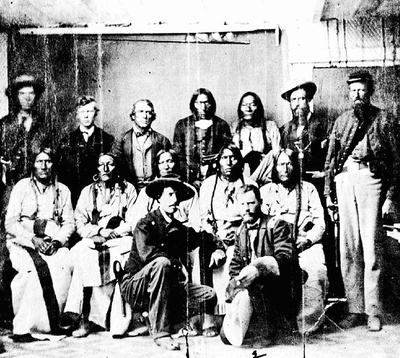

In 1864 Mrs. Amache Prower’s father, Chief Ochinee (a sub-chief working under Chief Black Kettle) helped negotiate a truce between the Cheyenne and Arapaho and the U.S. government. According to the truce the Cheyenne were guaranteed a safe camping site for the winter at their reservation along Sand Creek. But on the morning of November 28, soldiers from the Colorado First Volunteer Calvary rode onto the Prowers ranch and held the Prowers family and ranch-hands hostage, under house arrest.

—“Massacre at Sand Creek,” Dual Personalities

Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs meeting at the Camp Weld Council on Sept. 28, 1864. Standing, second from left: John Smith, to his left, White Wing and Bosse. Seated left to right: Neva, Bull Bear, Black Kettle, One-Eye, and an unidentified indian. Kneeling. Left to right: Major Edward Wynkoop, Captain Silas Soule.

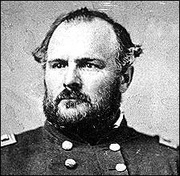

They were led by Colonel John Chivington, a former Methodist Priest.

During the early morning hours of November 29 (1864), he (Chivington) led a regiment of Colorado Volunteers to the Cheyenne’s Sand Creek reservation, where a band led by Black Kettle, a well-known “peace” chief, was encamped. Federal army officers had promised Black Kettle safety if he would return to the reservation, and he was in fact flying the American flag and a white flag of truce over his lodge, but Chivington ordered an attack on the unsuspecting village nonetheless. After hours of fighting, the Colorado volunteers had lost only 9 men in the process of murdering between 200 and 400 Cheyenne, most of them women and children.

—“Massacre at Sand Creek,” Dual Personalities

(Note: Amache’s father, Chief Ochinee (One-Eye) was also killed at this Sand Creek Massacre, the site, which “as the crow flies” is only 35-miles north of Amache, the WWII concentration camp. John Prowers, son-in-law of Chief Ochinee, was later called by the government to testify at the investigation of the Sand Creek Massacre held at Fort Lyon, Colorado.)

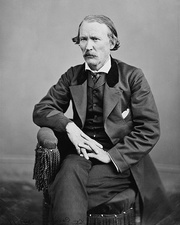

Christopher Houston Carson, legendary frontiersman, trapper, scout, soldier, and Indian agent better known as “Kit Carson” and a close family friend of the Prowers, had this to say about the terrible events:

Jis to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws, and blew the brains out of little innocent children. You call sich soldiers Christians, do ye? And Indians savages? What der yer ‘spose our Heavenly Father, who made both them and us, thinks of these things? I tell you what, I don’t like a hostile red skin any more than you do. And when they are hostile, I’ve fought ‘em, hard as any man. But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who would.

—“Massacre at Sand Creek,” Dual Personalities

Although he was never punished for his role at Sand Creek, Chivington did at least pay some price. He was forced to resign from the Colorado militia, to withdraw from politics, and to stay away from the campaign for statehood. In 1865 he moved back to Nebraska, spending several unsuccessful years as a freight hauler. He lived briefly in California, and then returned to Ohio where he resumed farming and became editor of a small newspaper. In 1883 he re-entered politics with a campaign for a state legislature seat, but charges of his guilt in the Sand Creek massacre forced him to withdraw. He quickly returned to Denver and worked as a deputy sheriff until shortly before his death from cancer in 1892.

—“John M. Chivington,” New Perspectives on The West (PBS)

Although the American Japanese experience of having their constitutional rights suspended during WWII by being ousted from their homes and places of business, relocated and incarcerated in assembly centers and concentration camps for the war’s duration without any legal recourse was very tragic, it can’t be compared in gravitas to the brutal treatment of the Native Americans, who lived in North America for over 800 years. People would state that even the treatment of enslaved Africans was a much greater injustice than that suffered by the Japanese, whose history in America was only two-to-barely-three generations long, but still for them too, freedom and justice was denied.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution that existed in the United States of America in the 17th to 19th centuries. Slavery had been practiced in British North America from early colonial days, and was recognized in the Thirteen Colonies at the time of the United States’ Declaration of Independence in 1776.

—“Slavery in the United States,” Wikipedia

Even at that time, “After the colonies revolted against Great Britain and established the United States of America, President George Washington and Henry Knox conceived of the idea of "civilizing" Native Americans in preparation for assimilation as U.S. citizens.”

—“Native Americans in the United States,” Wikipedia

This of course is not a contest of who suffered greater injustice, but should just be recognized in general as justice and freedom denied which should not have been taken from any groups of people. Hopefully, these human rights violations can serve as lessons to discourage future actions that would allow the “dominants” to perpetrate such crimes against vulnerable “others” ever again.

I hope the irony of the Native American name being used to name a concentration camp located in the vast Great Plains, land where the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians once successfully flourished and then where they were decimated can be seen. Where within a century, the WWII concentration camp named “Amache”was located, filled with a group of people, who because of their race were imprisoned without due process of their constitutional rights. These rights were not in place for the Native Americans and the Black Slaves in their days and even if they were, they might not have been respected and enacted upon such as was the case for the majority of Japanese living in WWII America.

Today, I’m proud to know that when there was mounting racism, growing fear and suspicion against Middle Eastern Americans following the terrorist’s attacks in America that the Japanese American community leadership spoke out against potential unwarranted reprisal against the group of people linked to the terrorists. We were fortunate to have Japanese Americans who were in key positions in the U.S. government to ensure that the constitutional rights of another race of people would not be violated.

John and Amache Prowers had nine children. All those who lived to adulthood went to college. John died in 1884 at the age of 46.

—“Massacre at Sand Creek,” Dual Personalities

In fact, Amache’s daughter-in-law, Mrs. John W. Prowers, Jr., a gracious, silver-haired lady, was still living in Lamar, Colorado, 15-miles west from Amache, the former concentration camp.

The National Park Service will be observing the 150th Anniversary of the Sand Creek Massacre and has produced this poignant photograph that graphically symbolizes that tragic 1864 event.

For more information regarding the observation of this anniversary >>

A planned 2014 Pilgrimage to Amache in May might afford the opportunity to pay tribute to both the Native Americans (Cheyenne and Arapaho) who perished in the Sand Creek Massacre and to the Japanese: Issei, Nisei, and Sansei who were imprisoned in a concentration camp named “Amache.”

For more information regarding the May 17, 2014 Pilgrimage to Amache, contact:

Frank Miyazawa: 303-237-8641 (English-speaking)

Hiroko Hung: 303-979-5127, e-mail: opiro39@hotmail.com (Japanese/English-speaking)

Bob Fuchigami: 303-679-2921, e-mail: bob.sally@comcast.net (English-speaking)

© 2014 Gary T. Ono