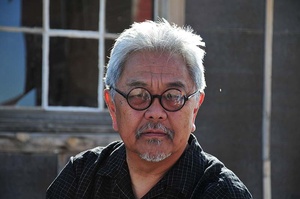

“It’s the best life in the world,” Roger Shimomura says, of being an artist.

“It’s unpredictable. You can be lucky, unlucky, work hard or not, be crazy or sane, and you have an equal chance to make a lasting mark.”

In a remarkable career that has spanned more than 50 years, 135 solo exhibitions, and a long list of awards, Shimomura, a Sansei (third-generation Japanese American), has used his art to battle stereotypical images of Asian Americans.

He is one of seven artists featured in Portraiture Now: Asian American Portraits of Encounter, a traveling exhibition from the Smithsonian, on view at the Japanese American National Museum (May 11 – September 22, 2013).

For Shimomura, who was unjustly incarcerated as a young child during World War II in Minidoka (Idaho), one of the 10 concentration camps for Japanese Americans, the fight against ethnic bias and misperception has been a lifelong creative passion.

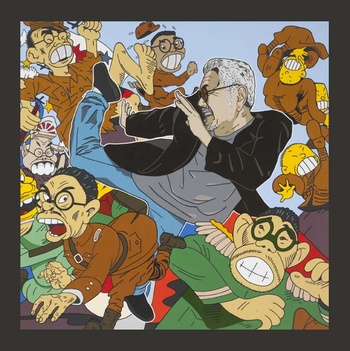

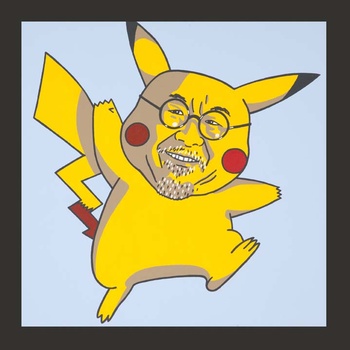

Shimomura is often known for taking “oriental” stereotypes, such as Fu Manchu-esque caricatures of Asian men, and visually skewering them in provocative ways, with vibrant colors and sometimes even a dose of humor.

“My approach to the art making process is socio-political in nature and (compared with many other artists) is like speaking another language,” he says.

“My biggest influences initially were the California Funk ceramics artists,” Shimomura says. “Their irreverence helped me break out of my conservative Asian thinking mode. These clay artists said in their works that nothing was sacred, that we needed a fresh start and needed to examine everything. There was a sense that art could take a leadership role in this revolution.”

He also expresses admiration for the Pop Art movement, which he credits for bringing an underappreciated–and surprising—intellectual basis for being artistic radicals. “Andy Warhol was my biggest influence, both visually, historically, and stylistically.”

Shimomura continues to find much to rebel against.

“The stereotypes of hard-working, studious engineering students, computer geeks, and martial artists persist,” Shimomura notes. “The model minority myth continues to plague and handicap Asian immigrants even though continued studies show these achievements are not entirely true. Two of my three children have succeeded without the benefit of a college education, a fact for which I am almost proud.”

AMERICAN VS. JAPS 2 by Roger Shimomura. Acrylic on canvas, 2010. Stretcher: 137.2 x 137.2cm (54 x 54") / Frame: 147.3 x 147.3cm (58 x 58") / Flomenhaft Gallery, New York. © Roger Shimomura EXH.AA.32

As a parent and also a longtime educator, now retired, Shimomura has recognized that Asian American perspectives can vary widely, depending on a person’s age and how far he or she is removed from the immigrant experience.

“There is considerable difference between generational attitudes in contemporary ethnic art,” says Shimomura. “There are the more recent immigrants that bring their cultural experience and knowledge with them and there are those that have been here a generation or two that become more like Asian wannabes in their work. Then there are those that have ‘melted’ without a trace of ethnicity.”

“I feel that I end up painting for my own generation because those issues that were so clearly hurtful in the ‘40s and ‘50s still pop up in recent years, vis-à-vis many of the comic stereotypes that returned during the Japan auto crises,” Shimomura says. “To experience that kind of hurtful response by the majority culture sprinkled all through one’s childhood through one’s adult years is quite disappointing. Younger generations—my own kids and grandkids, particularly living in multicultural Seattle—have a completely different perception of what being a minority is today.”

“I was sitting in on a panel at the College Art Association annual conference,” Shimomura adds. “Up front was a distinguished panel of artists who have devoted their careers to multicultural issues in their work. In the audience sitting in front of me was a blonde-haired Chinese American around 18-20 years of age. He was clearly annoyed at what was being said by members of the panel that were probably around 60 years of age. During the Q&A he raised his hand and said in a very loud and clear voice, ‘What’s up with you people? What’s your problem? Why do you feel sorry for yourselves? Why can’t you just be proud like me to be Asian?’ I would say that young fellow would feel differently about art than I do.”

In addition to generational differences, geography is also something that Shimomura has often considered in light of cultural understanding.

“I lecture around the country and have seen firsthand the difference between the way minority populations are treated and thought of by Midwesterners, East Coasters, Southerners, and people from the West Coast,” he says.

“It’s a mistake to standardize opinions without making reference to what part of the country one is referring to,” Shimomura explains. “Non-JAs (non-Japanese Americans) are typically more demonstrative in their responses to my work while JAs tend to quietly nod their heads in agreement. Yonsei in the more highly populated Asian locales tend to be least supportive of the work, suggesting these issues are ‘non-issues’ today. Where I live in the Midwest, many Asian Americans find a voice in my work.”

“Some of my biggest supporters as well, are Caucasian women,” he notes. “I think that they see similarities between the content of my work to the women’s movement.”

AMERICAN HELLO KITTY by Roger Shimomura. Acrylic on canvas, 2010. Stretcher: 45.7 x 45.7cm (18 x 18") / Frame: 55.9 x 55.9cm (22 x 22") / Flomenhaft Gallery, New York. © Roger Shimomura EXH.AA.28

While Shimomura has gained fans, his intent is often more to make a point than to please.

“I did a performance in NYC called K.I.K.E. that was my protest to the Jewish American Princess (J.A.P.) phenomenon,” he says, remembering one of his works of performance art. “My N.Y. dealer who is Jewish understood the piece which finished with the claim that Japanese American women called each other Kikes which stood for Kinky Immature Kimono Empress.”

“One Jewish collector cancelled her purchase of a large painting after she saw the performance,” says Shimomura. “Another fainted and had to be carried to the office to recuperate. No one really knew why she fainted. While most in the audience were apologetic and admitted to learning something, others felt I had no right to ever use the term KIKE under any circumstance, but that the word JAP was understandable.”

Shimomura sees his outspokenness as a key part of his artistic point of view. “The older I get, the less I am apt to be surprised by anyone’s reactions to my work. I am usually disappointed by the general apathy of the Asian American viewer that still questions the ‘appropriateness’ of creating a visual public forum for these issues. I think it embarrasses many of them particularly those that feel that I am bringing up what they’d rather ignore: dirty laundry.”

To ensure that the public forum remains well fueled, he is currently working on some new pieces that he hopes will spark further conversation about Asian America. These include a giant mural of activist Gordon Hirabayashi, and a series inspired by Pop Artist Tom Wessellman’s ‘Great American Nude’ series in which he plans some provocative juxtapositions of images. Not only for his own sake, but for the sake of the field, he hopes that collectors take note of these pieces.

“The healthiest thing that can happen to Asian American Art is the emergence of art collecting as an integral part of the Asian American landscape,” he says. “I have been quite vocal in Lawrence, Kansas, where I live, about the importance of an active art collecting culture. I am not referring to the type of collecting that stops when the walls are filled, but the kind where the collection is being constantly upgraded.”

“Imagine a competitive culture of collectors all of whom are trying to amass the most important collection of Asian American art,” says Shimomura. “Then imagine the improved level of debate about content. In the end the ultimate measuring device of the success of your career is who owns your work.

Shimomura’s long career in art almost didn’t happen. Like many Asian American parents of the time, his father wasn’t thrilled by the prospect of his son pursuing a creative profession.

“My father, who had to take the quickest way out of the University of Washington when the depression hit, became a pharmacist,” Shimomura recalls. “He held hope that I would someday fulfill his legacy and become a doctor. However, I was influenced by the successes of my uncles who were all graphic designers. The night before the first enrollment my father asked for a compromise. I offered—not very seriously—architecture. He offered dentistry—seriously. At that point it became abundantly clear there was no hope of compromise, so I majored in art.”

His advice for young artists thinking of following in his footsteps is simple.

“You first have to know that you have little control over becoming an ‘art star,’” he states. “All you can do is put yourself in a position for good things to happen. Art must hold the top priority in your life. Anything less will eventually turn you into a Sunday painter.”

“All I know is that if there is another shot at life, I want to be an artist again.”

AMERICAN PIKACHU by Roger Shimomura. Acrylic on canvas, 2010. Stretcher: 45.7 x 45.7cm (18 x 18") / Frame: 55.9 x 55.9cm (22 x 22") / Flomenhaft Gallery, New York. © Roger Shimomura EXH.AA.29

*Roger Shimomura’s artwork can be seen at the Japanese American National Museum in Portraiture Now: Asian American Portraits of Encounter from May 11 – September 22, 2013.

© 2013 Darryl Mori