Follow the story of “Rocky” Yamanaka, one of the few remaining Nisei who remembers life in Chicago before Japanese American resettlement, from his family’s difficulties in the Great Depression, his experiences in being drafted on V-J Day at the end of World War II, and his return to a Chicago that had drastically changed.

“My Japanese name is Iwao, which means ‘rock,’” explained “Rocky” Yamanaka, a Nisei who currently lives in the Lincoln Square neighborhood of Chicago’s North Side. “Because of that, my nickname became ‘Rocky.’”

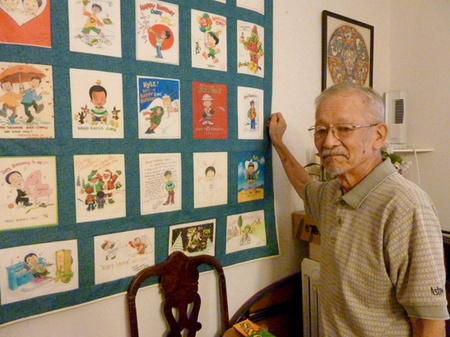

Still sharp of mind and looking rather spry for an 86-year old, Rocky Yamanaka, with his thin frame and graying hair, remembers a time before World War II when less than 400 Japanese Americans called Chicago their home. Currently, there are only a handful of Chicago Nisei from before the war that are still alive today.

Born in 1927 in the U.S. to parents who hailed from near Tokyo, his father first arrived in Chicago as a houseboy living with an American family in the early 1900s. Eventually obtaining an education and opening up a restaurant in the downtown area of Chicago, his father later married his mother and brought her back to the U.S. They would have two sons and two daughters, and Rocky was the third oldest of his siblings.

The diner owned by his father was on Clark Street near Chicago Avenue, and served American fare typical of the many restaurants run by Nisei at the time, since an American audience for Japanese food had not developed in the 1920s and 1930s. But following the Great Depression, his father would eventually lose the restaurant, though he ended up working for another Nikkei restaurateur.

By this time his family had moved from the south end of downtown and settled in a crowded, coal-heated two-flat in the Geneva Terrace neighborhood on the North Side of Chicago. Walking a block and a half to Lincoln Elementary School, he went to classes in a predominantly Caucasian community.

“Me and my sister were the only Japanese,” he said. “But we were curiosities to most of the Caucasians there. I was a very popular kid in school. I was a good athlete. I’d eat at friend’s houses sometimes and they’d eat at our house.”

His childhood memories included playing “kitten ball” (also known as “mushball,” a form of 16-inch softball popular in Chicago) with other Caucasian neighborhood kids. Early on he evinced a talent for drawing, and even received a summer scholarship to take a class at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Yet through his childhood, experiences of racism on the basis of his Japanese ancestry seemed rare, perhaps owing to the fact that the small Nikkei community was not seen as much of a threat in Chicago compared to areas on the West Coast, where virulent anti-Japanese sentiment had been the norm.

“Maybe somebody would call you a ‘chink,’” he said. “They wouldn’t call you a ‘Jap,’ because that wasn’t a bad thing until World War II started.”

Though his childhood friends tended to be Caucasian, he does remember attending Japanese American events, including community picnics with his family, as well as annual ceremonies honoring the Japanese Emperor’s birthday held on the South Side of Chicago. Another important memory involved going with a large group of Japanese to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair to see the Japanese Pavilion there, and having iced green tea for the first time, which was a relative novelty at the time.

When Rocky turned ten years old, his older brother developed rheumatic fever, a common childhood illness of the period. His brother ended up being treated at the La Rabida Sanitarium in Jackson Park (now the La Rabida Children’s Hospital), and since his family didn’t have a car, it would take them hours by street cars to go that far south. Later his brother returned home and though bedridden for a while, recovered enough to go to school. Despite his seeming recovery, his condition worsened and he passed away in May 1938.

Following the passing of his brother, his mother got ill for a long time, and then when she recovered, his father also got sick, due to an ulcer exacerbated by these family stresses. Rocky’s father would eventually pass away in December 1939. Both his father and brother were interred at Montrose Cemetery, one of the few cemeteries that accepted Japanese American remains for interment.

His father’s passing severely impacted his family and especially his mother. As he relates, “Once my father passed away, all of a sudden there was my mother, my older sister, me, and my younger sister, and we had no income. So from what I understand, we got on relief which was where the government gives you free food and clothing. In fact I remember getting some horrible shoes. But also, if you had to go see a doctor, the relief board would send you. I remember having my teeth worked on too. Yeah it was tough.”

Through assistance from the Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago his family eventually stayed in an apartment on Oak Street which the association ran. This experience provided his first significant exposure to the Nikkei community and through his time there he met other Nisei like himself.

“They had an apartment on the second floor, and they let my mother and us three siblings have one room in there to sleep in,” he recalls. “We were destitute, I think, and that’s where we ended up living.”

He would eventually learn a little of the Japanese alphabet there but never learned to speak Japanese like some of his Nisei friends. They stayed at the association from about 1939 through 1941, before his mother finally found employment.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, his family still lived at the association. Though he was only 14 years old at the time, he can still recall his thoughts today.

“I remember being down on the first floor when the news came over the radio that Japan had just bombed Pearl Harbor,” he recalled. “I said ‘what does that mean?’ Pearl Harbor didn’t mean anything to anybody. What’s Pearl Harbor?”

Lacking a strong family connection to Japan and being situated in the Midwest, the unfolding of the war seemed somewhat far away to Rocky as he went to high school.

“Here in Chicago, you were less aware of the war going on. Maybe on the West Coast and East Coast they were more concerned with submarines coming in or whatever. But here in the Midwest, they were just concerned about whether one of the mill plants was closing and making tanks and stuff like that. So the war was very far away.”

After his mother got a job they were able to rent a place on nearby Wells Street. His mother faced a great deal of difficulty in picking up after his father passed away, but she eventually worked in the restaurant business and ended up managing a restaurant after a couple of years, demonstrating her tenacity in the face of their family struggles.

During this time he attended Waller High School (now called Lincoln Park High School), first at the Waller branch before transferring to the main school for his last two years. At this school he met a number of other Nisei who attended as well.

By the time that he graduated high school in the spring of 1944, he fully expected that he would be drafted into the war effort.

“I was surprised I didn’t get called earlier,” he said. “When we were in our last year, a lot of the older kids were getting called out of our school. When I graduated I had just turned 17 and almost everybody I went to school with was older, and I heard that so-and-so went into the army or got drafted.”

“So finally I got my draft notice. August 14th, 1945 was when I had to report to the induction center which was downtown, and that was V-J Day. So I’m there and I’m signing papers, and a few little things are going on, and they’re taking my measurements or something like that.”

“And all of a sudden at maybe 8 o’clock or 9 o’clock in the morning somebody comes running in saying ‘The war is over!’ So here’s a bunch of us young guys, we’re being inducted and all the army personnel run out of the building. And you look out the window and people are running out of buildings and are celebrating down on the streets.”

Despite the war ending, Rocky still had to get inducted to fulfill his selective service duties. As he noted, he and his fellow enlistees were supposed to be sent to nearby Fort Sheridan by noon of that day.

“We didn’t get out there until after midnight,” he related. “It was pitch black… Half the guys are crying and half the guys are throwing up because it was such a weird day. It was just a complete mess. So that was my first day in the army.”

Following this, the army sent him to Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas where supplies ran low due to the consolidation of the armed forces at the end of the war. Three months later the army transferred him to Fort Snelling in Minnesota, but since he couldn’t speak Japanese he couldn’t join the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) program. By the end of his service he ended up at the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) school at Camp Holabird in Maryland and joined the art department, becoming a Staff Sergeant, and the head non-commissioned officer there.

In 1947 he finished his military service. Still only 20 years old, he found that his hometown had drastically changed.

As he said upon returning to Chicago, “I didn’t know anybody because they were all from the camps. And all my neighborhood Caucasian friends, some of them came back, but they were in the army too so they were going off to school in different places. So there was no neighborhood left.”

In speaking about the Nikkei that ended up resettling in Chicago from the Japanese American concentration camps, “Even before I got drafted they started coming into this area out of the camps. A lot of them moved to the South Side, like the Hyde Park area.” By 1947, the number of Nikkei in Chicago had rocketed to some 20,000 people.

With the war over, however, many resettlers ended up returning to the familiarity of the West Coast. As Rocky noted, “By the 1960s, there was only a tenth of what had been there before.”

Later he went to art school on the G.I. Bill and started a career as an illustrator at an art studio run by a former Disney animator.

Eventually, he joined a bowling league and met many resettler Nisei through that. As he said, “In the summertime I found out there was a bowling league and I knew how to bowl, and there was one at Clark and Division which was the hub of the Japanese American area. So I started bowling in the bowling league.”

All told, however, the Nikkei community had changed drastically from what he had known before. As he related, “The pre-war community no longer existed when I came back. I never did have a community, because I lived in a Caucasian neighborhood, but I had to move into a Nisei group. Then I went in the army and came back and the Nisei group was completely changed from what I remembered from two years before.”

“So I learned to integrate into this new Nisei group, playing golf, going bowling, and I even married one. And my kids grew up with a lot of Sansei kids that all have families from the West Coast so they have ties that I never had.”

Nowadays, he notes, the Nikkei community is more dispersed than before. As he relates, “As far as a community, the Nisei community is almost gone. They’re all in their eighties. The Sansei kids have spread out. Some of them are still holding the Japanese community together, but the majority of them marry Caucasians and are accepted in Caucasian neighborhoods with their businesses.”

Despite the changes that have taken place in the Nikkei community of Chicago, Rocky continues to live as an embodiment of an era now gone, but for him, and thankfully because of him, it will not be forgotten.

*This article was originally published on Nikkei Chicago on September 14, 2013.

© 2013 Ryan Masaaki Yokota