Read Part 1 >>

In contrast to Kawakami and Minami’s discussions that focused on the fact that it was the incremental gains of specific legal victories that lead to the redress in the U.S., it was very interesting to learn from Justice Omatsu that the Canadian road to redress was, comparatively, much more collectivist and political in nature. In Canada we had no banner cases or new “bright line” precedents to turn to, but the fight for the hearts and minds of those with the power to acknowledge and make restitution for the internment was no less of a struggle.

The audience was particularly interested in Justice Omatsu’s contrasts between the JC and JA internments. The fact that the Canadian internment included the separation of families, the confiscation and sale of property, and exclusion from the west coast until 1949 appeared to come as a surprise to many in attendance and both Minami and Kawakami later commented on the fact that after years of detailed research into the U.S. internment, they didn’t realize that the JC internment had been as comparatively egregious as it was. There were several audible gasps from the audience during Justice Omatsu’s presentation as she recalled specific experiences along the road the redress.

One of those moments came when Justice Omatsu told the story of Aki Otsuji. Otsuji’s story is recounted in detail in Ken Adachi’s The Enemy that Never Was, and Omatsu’s own Bittersweet Passage – Redress and the Japanese Canadian Experience. Otsuji was eighteen years old when he went to Vancouver post-War to be with his family as they were “repatriated” to Japan by the Canadian government; a process through which the Canadian government offered anyone of Japanese racial descent—including those born in Canada, free passage to Japan (i.e. deportation) if they agreed to renounce their Canadian citizenship at some future date.

At the last minute, Otsuji decided to remain in Canada, and, against the government ordered hundred mile exclusion rule—which forbade anyone of Japanese descent from living within 100 miles from the west coast of Canada (which lasted until 1949), he remained in Vancouver after his family set sail for Japan. Otsuji succeeded for a time hiding among the Chinese Canadian population but he was eventually picked up by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He defended himself at a trial that is reported to have lasted five minutes, and he was immediately found guilty and sentenced to one year of hard labour.

Accounts at the time suggest that Otsuji spent most of his prison term in “the hole”, bitterly weeping. He had only periodic contact with his family post-War, and was reported to have been the subject of the “revolving door” of institutional care in the years following, circulating among the indigent population of what was once Vancouver’s Japan Town. Otsuji last communicated with his family in 1977, when he explained to his sister that he couldn’t have contact with her, fearing that family ties would cause his disability benefits to be cut off. A decade later his body was found by his landlord in a seedy rooming house in Vancouver’s downtown east side.

While Dale and Rod successfully had the convictions of Hirabayashi and Korematsu expunged on the basis of individual Bill of Rights challenges, no comparable option existed in Canada. Only a “pardon”, which would inevitably suggest a benevolent act by a faultless government, could be achieved in Canada. On learning that a meagre “pardon” was the best case scenario remedy that could be achieved in Otsuji’s case, plans for individual appeals were dropped and the NAJC concentrated their efforts on direct negotiations with the government.

I began my portion of the discussion addressing the importance of the redress to all governmental apologies that followed it in Canada.

The legacy of the Canadian government using the Japanese Canadian redress as a legal framework began with the Krever Inquiry that acknowledged government negligence in failing to screen for HIV/AIDS in the Canadian blood supply against overwhelming evidence demonstrating that the disease was blood-transmitted. The government formally apologized for its conduct and granted redress to those infected with HIV/AIDS as a result, in 1993.

The legacy continued with the official recognition and apology regarding the Chinese head tax in 2006, which acknowledged that the government’s legislated collection of a special “tax” to be paid only by Chinese immigrants to Canada (which had lasted from the late 19th Century through 1923) had been immoral and unjust.

The legacy continues with the current Indian Residential Schools System Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up to address the many wrongs of the residential schools system in Canada that forcibly removed native children from their communities toward the then-government sanctioned goal of irradiating native cultures in Canada.

In addition to highlighting the importance of official governmental acknowledgement and apology, the Japanese Canadian redress established two very important principles. First, that redress itself is most effectively provided when the parties that were harmed by the offending governmental action (or failure to uphold a duty to protect them) are involved in the process; the establishment of the principle that recognition and respect are as important as the apology. Second, although it is acknowledged that payments in redress could never be deemed sufficient to right the wrongs that they are intended to acknowledge, making those payments is simply the right thing for the government to do as part of the redress process. The latter point remains somewhat controversial in Canada, as payments don’t always necessarily follow redress, as was seen in the case of the Chinese Head Tax, which resulted in an apology, but no payment.

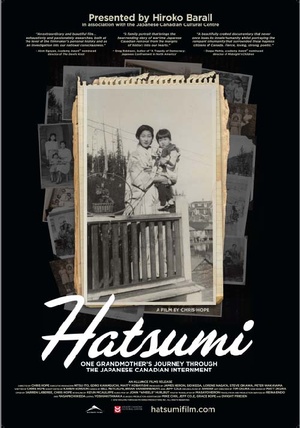

Turning to the “relate” portion of the program, Jeff Hsi provided background regarding Hatsumi. Hatsumi is a film that I’ve spent the last eleven years making. It covers my grandmother’s journey through the Japanese Canadian Internment, and effectively leads viewers through the history of the internment, from my grandmother’s perspective. It was released on DVD in Canada on November 27th, and I hope to be able to bring it to the U.S. soon.

Jeff began by asking me what drove me to make the film. My concise answer was that I wanted to create a tool that will help my generation to ‘get’ the internment.

Textbooks don’t cut it when it comes to relating the personal devastation that the internment caused, and in the absence of any personal gravity, the internment story is often glossed over, forgotten and, worse, in danger of being repeated as a result. Further, the redress has had the effect of creating the sense that it’s fine to forget the internment because all has now been made well. Too often when dealing with media people say “…it was bad, but they didn’t they get paid out in a redress?” If only it was that simple.

To conclude our panel, Dale Minami reminded the audience that it is critical that we continue to discuss the internment and to teach it through whatever means we have available. As long as governments consider legislation that will affect the rights of individuals, it is our duty to provide them with the benefit of lessons learned in the past.

Both from my perspective as a lawyer and as one concerned with the preservation and understanding of the civil rights history that our combined Japanese American and Japanese Canadian communities, the NAPABA conference experience was an incredible one for me. After years of reading about them in books, sitting in front of an audience beside Dale, Rod and Maryka was quite surreal. The enthusiasm with which they welcomed me reminded me that we are members of a larger team that has much to do to ensure that our combined heritage and experience is preserved and remembered.

In closing, I’d like to extend my thanks to Ann Sunahara in Ottawa for her generous consultation in the course of my own preparations for the NAPABA conference. Ann is the author of The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of the Japanese Canadians During the Second World War, which she has made available online—free of charge—at www.japanesecanadianhistory.ca.

© 2012 Chris Hope