Read Part 3 >>

The Photographic Documentation of Manzanar

As Fujikawa, Alinder and Hosoe all noted, photographs of the World War II prison camps can be just as misleading as the rosy accounts of those who were imprisoned. So much so that the writer and lawyer Gerald H. Robinson titled his examination of the Manzanar photographs of Adams, Lange, Miyatake and Albers Elusive Truth. Still, it is valuable to explore how documentary photography, in the hands of talented photographers, can manipulate the viewer’s perceptions and mean such different things to viewers in different eras.

Adams’s book on Manzanar, Born Free and Equal, was published as a cheaply printed two-dollar paperback in June 1944. Featuring 64 of his photos and text he wrote himself, it was among the top ten books sold in San Francisco that year, although it was poorly distributed beyond the Bay Area. In his later years, Adams claimed that the military had confiscated a large number of copies and destroyed them because of its perceived anti-Americanism. At the time of publication, some critics praised Adams for his moral courage while others vilified him for sympathizing with the enemy.

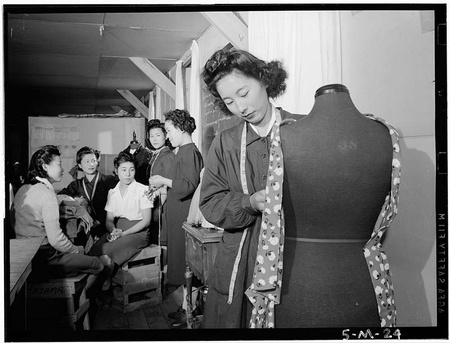

The pictures of inmates in Born Free and Equal contain a sense of optimism, possibility and a reverence for nature. Beautifully composed and printed portraits and descriptions of their subjects’ vocations are interspersed with Adams’s typically heroic landscapes, suggesting spiritual redemption beyond human suffering, and pictures of industrious prisoners at work and play. A young man, grinning widely, hugs two giant cabbages, one in the crook of each arm. Two men fix a tractor. A group of young women, tape measures around their necks, receive vocational training as seamstresses from another prisoner, a dignified-looking older woman. A uniformed United States cadet nurse smiles sweetly for the camera. Spectators along the sidelines of a baseball diamond watch a game in progress. Suffering and want are absent. These are pictures that could have been taken in any small American town, only the faces are all Japanese.

Adams's caption for this photograph of a dressmaking class at Manzanar in "Born Free and Equal" read, "The young people receive extensive vocational training." (Source:Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

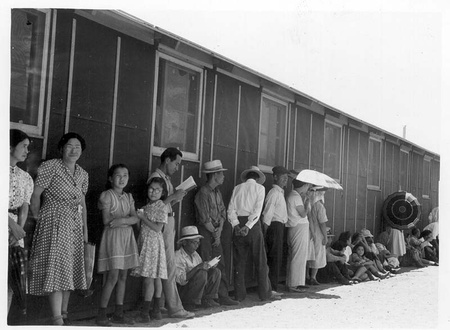

Dorothea Lange’s photographs of Manazar are of a different tenor altogether. Her images emphasize the make-shift conditions and echo the sense of hardship and loss found in her Farm Security Administration photographs of the 1930s. In one, a line of stoic internees presses against a barrack wall to stay within the building’s thin ribbon of shade as they wait for lunch in the mess hall. A more forlorn shot shows the grave of the first person to die in camp, a simple dirt mound surrounded by stones and a squat, rough-edged obelisk at its head. An interior scene of a barrack apartment shows cloth partitions hung as room dividers with three generations of one family—a grandfather, mother and baby, and possibly the woman’s husband—huddled around a stove for warmth.

Lange preferred to focus on the tedium, discomfort and injustice of the concentration camp. Here, prisoners wait in line for lunch outside the mess hall at noon. (Source: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Series 8: Manzanar Relocation Center)

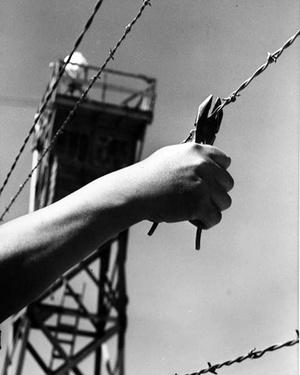

Photographs taken by the imprisoned Toyo Miyatake resemble propaganda the least. They present a matter-of-fact rendering of life in camp, a visual record of what happened. Miyatake’s camera served as a prisoner’s log, a way of marking the days, capturing the quotidian activities that at first glance appear so innocuous: the baseball games, sock hops, vegetable gardening, craft shows and graduations. Yet Miyatake’s are the only photographs that depict the guard towers and barbed wire of the camp, and the flowering of traditional Japanese arts that occurred among a population with more time on its hands than it had ever had before. Since WRA regulations prohibited depictions of prison camp guard towers and fences, Miyatake the inmate first photographed clandestinely, with a makeshift camera made of smuggled in parts, then later with official permission. He also had no fear of photographing culturally specific pastimes; this was his community, and his intention was to record what happened, not to influence the views of a target audience.

Miyatake had his son Archie pose with a pair of pliers as though to cut through the camp's barbed wire for this photograph used in the 1944-45 Manzanar High School yearbook. The bittersweet caption read "through these portals...to new horizons." Graduating seniors were preparing to leave the concentration camp for uncharted futures. (Photo by Toyo Miyatake, courtesy of Alan Miyatake, Toyo Miyatake Studio)

Static and unchanging, these documentary photographs, especially those of Adams and Lange, are relics that continue to elicit conflicting and shifting emotions. (Miyatake’s have been less publicized and so presented far less frequently.) Buffeted by history, they have been alternately suppressed, criticized and celebrated as different generations viewed them with fresh political sensibilities. Were Adams’s photographs an accommodationist view of the U.S. government’s imprisonment of 110,000 Japanese, tacitly concurring with the assessment that Japanese immigrants and their American-born children represented a threat during a war with Japan? Or was he a crusader for their rights? These dramatically different critiques made over the past six decades reflect the evolving views of the imprisoned Japanese themselves.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto