"Everywhere there is community feeling to be mended, vicious legislation to be defeated, many urgent jobs calling for attention from real friends of the real America."

--Letter from Friends of the American Way

Whether through principle or personal attachment, true friends of Japanese Americans did not abandon them after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when in public perception they were suddenly equated with the enemy. Interviews and documents preserved in the Densho digital archive give poignant testimony to the consolation that Japanese Americans felt when schoolmates, neighbors, and customers stood by them in spring 1942 and during their years of incarceration. Less cheering are the stories of long-time acquaintances turning their backs on Japanese American families when they most needed moral and financial support. While there is ample documentation of opportunistic Caucasians taking advantage of a population forced to "evacuate" at a week's notice, Nisei interviewees also remember incidents of selflessness that help offset stories of self-interest.

Because most Nisei were in their teens or early twenties in 1942, many of the recollections Densho captures are told from the perspective of students. Seattle accepted refugees from Europe before war broke out, and at one of the city's junior high schools, Henry Miyatake befriended a boy who had the "most interesting story" of the entire class, shared in an essay read aloud:

Yes, he was asked to read it. And he was telling about the persecution of the Jewish people by the Germans. It was kind of unbelievable at that time because in the newspapers they would cover the stuff in a general form and they weren't talking about the uncivil behavior of the Germans towards the Jews at that time, not in the sense that we know it today. But he stated it very candidly and he told about his own family and how they were able to escape from the system and get to the United States...

He made this paper presentation, I think, October 1941, and this was before the war started. But you know, the war clouds were getting darker. And this thing about the last boat to Japan, it was in the newspaper, it was about that same point of time. He was concerned about whether or not there was going to be war with the United States, with Europe and also in Asia. He felt very comfortable being in the United States. But come the Pearl Harbor Day and the day after when we went to school, he told me all kinds of things are going to happen.

The boy was from a wealthy, educated family that had escaped through a network in England and New York. He tutored Henry in math, and in return Henry helped the boy in shop class. Teachers told the students not to talk about Japanese Americans being taken away, but somehow Henry's friend knew. When the teacher announced, "Tomorrow will be the last day for some of the students here," Henry's friend spoke up:

In the homeroom class, he was emotionally distraught. He stood up and said, "I didn't come to the United States to see this kind of thing happen. I don't know what's happening here, but this is not what I came for." And he made a very impassioned speech. He was very disturbed. But that's the way things were going at that time. He was more perceptive than I was.

When Henry returned to Seattle after leaving camp, he tried to find his friend but was told the family had gone back to New York. Henry remembers their last exchange: "The last day I was there, he did have an envelope for me. He put it into my pocket and said, 'Well, maybe you could use this one of these days.'" What was in the envelope? Henry replies, "Money."

In San Jose, California, Jimi Yamichi's family operated a truck farm. Their best customer for years was the "very, very big" Consolidated Produce company. From 1933 the buyer, Ted Myer, a diminutive man like Jimi's father, purchased the best produce local Nisei farmers could provide. Jimi recalls how Myer and his father would drink and relax together after work was finished, enjoying each other's company despite the language barrier.

December 7th the war broke out, and late in the afternoon Ted Myers came by the house and told us -- he always called my father Yamaichi: "Hey, Yamaichi, I have to go to Los Angeles. My boss is calling me." He never liked to take a train so he drove down there. And Wednesday he came back. He didn't go home. He came directly to our house. We were surprised to see him back, "Back so fast?" He says, "Yamaichi," he leaned on my dad shoulder -- he's about the same height -- he cried. He says, "Yamaichi, they'll put all of you away. The big boss told me to look at all the farmland. 'Get the best farmland you can, and all the equipment, and see what you can buy. We'll buy everything. All these Japanese farmers'll be all gone, so prepare yourself and take inventory of the farms that's available that you think we should buy.'" And after that, Ted Myers was very, very disappointed. He just said he told his boss, "I can't do it." These people were good to him, all these years we were faithful to him.

When the exclusion orders came, the Yamaichis thought about sacrificing the farm and voluntarily moving east, but another family friend, of French descent, offered to oversee their farm while they were gone. Of his own accord, Charles Buron collected rent from tenants, paid the taxes, and reported each month on how much money was in the bank. When the family finally escaped tumultuous years at the Tule Lake, California, incarceration camp, they had the farm to return to.

Densho interviewees report mixed behavior among people they had considered friends before the war. In Fowler, California, Yoshimi Matsuura recalls some who started to use the word "Jap," and were happy to buy the family's tractor at half of its worth after the exclusion orders were posted. In contrast, while Yosh was detained at Gila River, Arizona, he learned that "Ma and Pa Kellogg," his civics and American history teachers, had been driven off of their farm for being too outspokenly supportive of their former Japanese American students.

Another demonstration of principled friendship at a personal cost took place at Bainbridge Island, Washington, where the Army removed the first Japanese American families under the authority of Executive Order 9066 in March 1942. Earl Hanson, who took time off from work to say goodbye to his many Nisei high school friends, remembers how Walt Woodward, editor of The Bainbridge Review , braved islanders' anger when he printed sympathetic reports about their missing Japanese American neighbors. (Woodward served as the model for the protagonist of David Guterson's novel Snow Falling on Cedars .) Hanson says, "Walt Woodward, you've got to pat him on the back because, boy, he stuck up for the people through thick and thin. And a lot of people quit buying the paper, they quit advertising, but he bulldozed his way through." In a letter to the editor, Ichiro Nagatani, on his way to captivity at Manzanar, California, told Woodward, "I really want to try and put across to you how much your friendship has meant to us…You were one person who had faith in us." His letter of thanks is followed by a reader's cancellation notice.

Some Nisei remember friends visiting them behind barbed wire and sending requested items to them in camp. Authorities didn't make it easy for outside communication; strict restrictions applied especially in the early days, and packages were inspected and sometimes confiscated. Paul Bannai, who had overcome discrimination to obtain a job at a bank in Los Angeles, recalls his friends' frustrated attempts to visit him at the Manzanar, California, incarceration camp.

I remember that even though I was in camp, I had a lot of people that were friends outside. When I left the bank and went up there, one of the accounts was a company that had a lot of audio and visual equipment, and because they heard that I couldn't take a radio, they sent me a radio by mail. Well, unfortunately the camp director said he'd have to turn it down. But I had friends like that that would try to help in every way possible to make my life in camp a lot easier because they didn't know what the situation was. They were never allowed to come to Manzanar. They couldn't visit. They couldn't come in. In fact I remember one time that the gate at Manzanar -- they were very strict, nobody was allowed in. And any time that the so-called non-Japanese came to visit, they were not ever allowed into the camp.

While the memories of young adult Nisei resonate with viewers of the oral histories, perhaps even more poignant are artifacts in the Densho collection that preserve the feelings of children caught up in events beyond their understanding. Letters from Nisei students removed from Seattle's Washington Junior High School capture their efforts to remain cheerful, even as their words reveal starkly changed circumstances. A boy named Tokunari, held at the Puyallup Assembly Center on the Washington State Fairgrounds, writes to his teacher and past classmates: "We have one room shared among 7 pupils and the walls are full of holes and cracks in which cold and chill air struck us in a funny way that I could not sleep at all last night. We had so little to eat that after reaching our room I ate a sandwitch and some crackers. Our beds are on loose by the U.S. Army and our mattress is a cloth bag strawed by hay." He signs the letter, "your Seattle evacuee."

A girl named Mary, also at Puyallup, adds a postscript in a letter to her former teacher, "P.S. Please write to me, and the class also because it is lonely here." In answer to her classmates' questions she says, "We wait in long lines for our meals" and concludes, "The lights must go off at ten o'clock so I must stop." Mary doesn't add that when the barracks lights go off, sweeping searchlights go on. She finishes another letter, "When I'm not doing anything I think about Washington School and the children in it. Thank you for the letter and jokes. They gave me a good big laugh." She signs the letter "(who was) Your classmate, Mary."

As a young boy, Emery Brooks Andrews visited his Japanese American friends at the Minidoka, Idaho, incarceration camp. His father, Reverend Emery Andrews of the Japanese Baptist Church in Seattle, moved his family to nearby Hunt, Idaho, and braved insults and threats of the locals for his decision to minister to his displaced congregation. Japanese Americans fondly remember how Reverend Andrews drove back and forth from Seattle to see to their affairs and bring them belongings left behind. Brooks remembers seeing his friends' new surroundings during what was "a fracturing time" for everyone: "I have vivid memories of driving up the road to the guardhouse, to the gate there and seeing the barbed wire fence stretching, it seemed like for miles around the camp. And the guard towers, soldiers in the guard towers with guns, always pointing in toward the camp, never out."

One group of friends in name as well as deed figures prominently in the story of the Japanese American incarceration. The Society of Friends, or Quakers, adhered to their pacifist and humanitarian beliefs as they firmly opposed the forced removal and detention. Densho interviewees remember receiving Christmas presents donated by Quakers, learning about their constitutional rights from Quaker teachers in the camps, and staying in Quaker-run hostels after leaving confinement. Friends committees sponsored Nisei out of the camps and into colleges, and they helped former detainees find scarce jobs after allaying the fears of hostile communities.

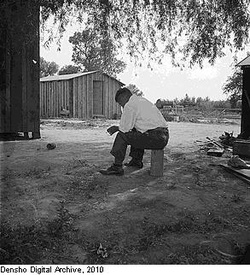

Floyd Schmoe, a Quaker from Seattle (pictured in photograph at head of article), was an ardent advocate for Japanese Americans before, during, and after the war. He traveled to Hiroshima to help build housing for the atomic bomb victims, and assisted the redress campaign in the 1980s. Upon obtaining files compiled by the FBI, Schmoe learned that the government had contemplated filing charges against him but declined. Someone with a blacked-out name had called him "a yellowbellied Jap lover, " apparently deemed insufficient evidence for arrest.

The Quakers launched letter-writing campaigns to push for the release and resettlement of incarcerated Japanese Americans. A report from one Quaker committee, the Friends of the American Way, reveals that these were friends not just of individuals unfairly imprisoned, but also of the democratic principles that should have protected them:

Everywhere there is community feeling to be mended, vicious legislation to be defeated, many urgent jobs calling for attention from real friends of the real America. What is your community doing?

* This article was originally published on Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

© 2010 Densho