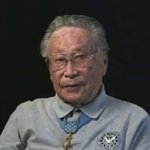

“I’m no hero, but I wear it for the guys that didn’t come back.” — George “Joe” Sakato

George T. Sakato is the great-great-great-grandson of a samurai. Perhaps that explains his father’s choice of a birth name. Sakato says, “Dad wanted to call me Jyotaro Sakato, after a sword-bearer for Musashi samurai.” But when the doctor submitted the vital statistics for the baby, “Jyotaro” became “George.” An unassuming man, Densho’s interviewee says simply, “All my life I’ve been called Joe.” On October 29, 1944, in the Vosges Mountains of France, Private Joe Sakato’s warrior ancestry saw him through a critical juncture in the storied Battle of the Lost Battalion.

Among the Nisei veterans who have shared their memories of combat for the Densho collection of oral histories, Joe Sakato tells an exceptionally riveting account of fighting in Europe with the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He volunteered for the Army in March 1944 from Glendale, Arizona, where his family had moved from Redlands, California, during the “voluntary evacuation” period. During his time in Arizona, Joe lost thirty pounds doing farm work in the extreme heat. He also did a little bootlegging at the nearby Poston incarceration camp.

Click to enlarge. Minidoka Irrigator, Date: February 3, 1943, Minidoka incarceration camp, Idaho. Densho Digital Archive, 2009.

Joe’s first attempt to volunteer was met with rejection. Like other Nisei, he discovered the military did not want him: “I volunteered for the Air Force, but then my draft card says 4-C, enemy alien. ‘Enemy alien? What do you mean enemy alien? I’m an American.’ ‘Your draft card says 4-C, enemy alien, we can’t take you.’” After the 100th Battalion of Hawaii Japanese distinguished themselves in Italy, President Franklin Roosevelt permitted the formation of a volunteer unit from the mainland, which became the highly decorated 442nd.

Joe volunteered again in March 1944. He recalls, “So I signed up for the Air Force and I got on a train and I got out to Camp Blanding [Florida], and I’m looking out and I says, ‘Where’s the Air Force?’ ‘You’re in the infantry. The 100th Infantry Battalion needs replacements for the wounded that was killed, and they need soldiers to replace them.’ So I’m it.”

By his own admission, Joe was not hero material. He had been a sickly child (“I was skinny and I got pneumonia, chicken pox, measles, anything that came by”). At five feet four inches tall, he was the smallest of five brothers. In basic training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, Joe says with a laugh, “I could crawl, but those little eight-foot, ten-foot-high walls, I could never climb up those. I went around ‘em.” He claims to have been a poor marcher and worse shooter:

They had a big door out there, target, 200 yards, height and windage, bang. And they had this red dot on the end of a pole, ten-foot pole, and that red dot would indicate target, part of the target to hit. One guy hit it up there, another guy would hit over here. When it came to me, I got this waving thing called Maggie’s drawer. I missed the target? I didn’t hit the target? I didn’t even hit the target. Oh my god, I couldn’t shoot that rifle. I didn’t know, too much windy or too much elevation...

Nisei soldiers visiting their families, Granada incarceration camp, Colorado, June 1943. Densho Digital Archive, 2009.

Before being deployed to Europe, Joe and friends took a side trip from the New Jersey base. Joe had a bright idea: “So me, Tanimachi, John Tanaka and Sho Tabara and another fellow, we all went to New York City, and we’re looking up, all these big high rises, and so we says, ‘Why don’t we check into the Waldorf Astoria to say that we stayed at the Waldorf Astoria?’ So we each put ten bucks apiece, cost us forty dollars to go to this Waldorf Astoria, and we only stayed there for five, three or four hours looking out the windows.”

Then came the 28-day ship’s journey to Europe, memorable for seasickness and enemy submarines. Upon arriving in Naples, the recruits were divided among platoons; Joe was sent to the 3rd Platoon, E Company. After more basic training in Marseilles, he learned about combat in August 1944 in the Vosges Mountains of northeastern France.

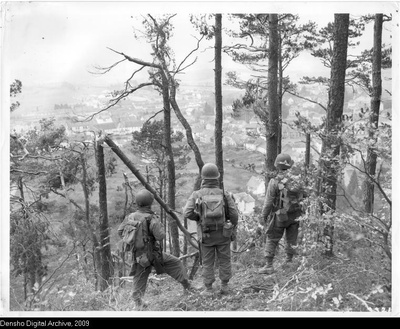

Sakato: Going up to Epinal, we took these trains, they go up five miles and then they would back up two miles and wait, then they go one, five, six miles and they’d back up. They finally put us on trucks and trucked us just this side of Epinal, and from there we had to start marching. So we marched towards the hills, raining, muddy, mud’s up this deep…So we got to the area, and then we had to climb that hill. But the damn thing’s about a forty-five degree angle, and you’re trying to pull yourself up, and I couldn’t get up and I had my pack, George Kanatani takes my pack, somebody else took my shovel, all I had was a rifle. Pulling myself with the tree roots, I was the last one up the hill. The damn hill, god, I couldn’t climb ‘em. I’d have to rest every feet I go, and then I get another ten feet. So when I finally got up there, everybody else was already up there...

Densho: But they all helped you, though, Kanatani carried your pack, somebody else took your shovel...

Sakato: Somebody else took my shovel.

Densho: And was that the spirit of the unit, that everyone would try to help each other out?

Sakato: Oh yeah, helped each other out.

Joe’s unit went to battle under the command of a “90-day wonder” lieutenant, a quickly trained and unprepared officer who fled during the fighting.

So then first day of the battle, 1st Platoon and 2nd Platoon are ahead, but couple thousand yards ahead, and we’re back in reserve, 3rd Platoon. We had a new “90-day wonder” lieutenant join us named Lieutenant Schmidt. He was kind of worried, he’s pacing back and forth, everything’s quiet and he’s nervous as all hell. So I stuck my two fingers under my nose and I, “Sieg Heil in case we lose.” I thought he would laugh, he chewed me out. Then artillery shells started coming in... I tried to humor things, make people laugh. And other guys laughed but he didn’t laugh; he chewed me out for that. So artillery shells, now I hear this one coming in, boom. That was incoming. I found out what incoming was. But when you hear it, little fluttering, that’s outgoing, that was our guns going. But when you hear something go “vroom,” that’s incoming. So when that came in, blew me up and I was over there, ten feet, and ached all over, and got up, sores all, looked, and I got a nick here. But I looked down, Yohei Sagami from Wenatchee, Washington, was talking, we were talking what are we going to do when we get out and this and that. He’s laying down, facedown, I picked him up, turned him over, he got hit in the jugular vein, and the pulse, blood was coming out every time he’d, pulse beating. And I couldn’t stop it without choking him. I tried to put a pad on there, but still, he couldn’t breathe, and had relaxed, but blood was coming out. Medics came, but he died, he’d lost too much blood, he died. So that was my, one of my first buddy dying.

With German tanks approaching, Joe dug for cover while checking for landmines. “I had to think back,” he said, “Why, what am I doing here? I volunteered for this? So I went, kept on going, then we had, finally took the hill. I Company is down below, they had to go around and they went into the town of Bruyeres, hand to hand combat, house to house.”

Exhausted after the bloody fight to liberate the towns of Bruyeres and Biffontaine, the 442nd was within days sent back into combat. They were ordered to save a trapped unit of the Texas National Guard. The “Lost Battalion” was encircled by German forces, cut off from supplies. Two attempts to free them had failed when General John Dahlquist ordered the Nisei soldiers to save the Texans. On October 25, 1944, the 422nd advanced in the dark and foul weather, fighting from tree to tree. Joe’s E Company was ordered to circle behind enemy lines in an attempt to secure a hill where Germans were firing down on the advancing Nisei troops. They marched single file, silently in the night, to surprise the Germans at dawn.

We chased the Germans off, and then artillery shells started coming in. So then we had to jump into the German foxholes now. So I’m on the bottom, ran to one foxholes, and artillery shells are coming in. Another guy from F Company, he jumps in. I didn’t know who was jumping in with me, pretty soon I recognized him. “Hey, you’re Mas Ikeda from Mesa, Arizona.” He said, “Yeah.” “What’d you hear about home?” We talked about home and the artillery shells were... boom, bang, didn’t bother us a bit. We were talking about home. It’s good to hear somebody talk about home. Artillery’s going off, somebody else is hollering for medics, somebody else was... but it didn’t bother us.

Artillery shells stopped, counterattack, so Mas Ikeda had to jump out of his foxhole, go to F Company and regroup… Next thing you know, I ran out of ammunition, both clips were gone. One German wanted to come up, going to throw a grenade at me. So I took the pistol, I couldn’t get the other clips out, so I got the pistol, and pow, pow, stopped him. Then no more troop movements, and so I got down in the hole and started filling my clips up. Pretty soon I’m looking uphill, Germans would be down below. But they went around me while I was down in the hole, I didn’t see ‘em, and they started climbing that hill, they started taking the hill back. “Oh, my god,” I started hollering at the guys, “watch out for the machine guns, they’re taking the hill back.” And Tanimachi, for some reason he got up and says, “Where?” and he got shot. So I crawled over to his hole and picked him up, “Why did you stand up?” And he’s gurgling and he’s trying to say something, blood is coming out of his... and he just, then he just went limp. Then he went, body went limp on me and then I knew he died. And I cried, hugged him, and, “God, why?” Laid him down and looked at all the blood in my hands and I said, “You son of a bitch.” Picked up, threw the pack off, picked up the tommy gun and I got out of the hole and I zig-zagged back up, run this way and I’d run that way. I shot two or three guys, and then pretty soon the guys with white handkerchiefs were waving them, group of ‘em coming out, and I made sure that nobody behind ‘em had a gun, otherwise I would have had to shoot him. So the rest of the troop came up and took the hill.

Click to enlarge. Granada Pioneer, November 15, 1944, Granada incarceration camp, Colorado. Densho Digital Archive, 2009.

The soldier who had so much trouble ascending hills explains, “If I was in my right mind, I don’t think I would have done that. I’d have stayed in my hole and shoot, but then to go up and charge the hill was something else that I, I wasn’t quite in my right sense of mind. But I was just mad, crying, I was crying.” For his actions, Joe was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, hastily pinned on before he flew home to recuperate from a battle wound.

In the six days of brutal combat, over 200 Japanese American soldiers were killed or wounded to save as many Texans. Some have questioned the relative value placed on Japanese American versus Caucasian lives. Joe himself uses the term “cannon fodder.” In 2000, Joe Sakato and nineteen other Nisei soldiers (most posthumously) had their decorations upgraded to the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony.

To recover from the war trauma, Joe traveled and opened up about his experiences: “If I had to stay home and think about the war, you know... I have to talk about it. If I had to keep it in here, I think I would go crazy. That’s why I thought in my mind I’d rather talk about it, so I’d get it out of my mind.” Even now, Joe has occasional nightmares about combat. He has made a point of speaking, to any audience who cares to listen, about what the Nisei soldiers went through while their families remained in detention camps.

Joe Sakato is a modest man. On receiving the Medal of Honor, he declared, “I’m no hero, but I wear it for the guys that didn’t come back.” Joe concludes with a laugh, “After ninety days of battle, all I had was nine months in hospitals, basic training, and a total of eighteen months, total service. That’s why I’m just still a recruit, I’m still a private. I’m going to stay a private.”

* This article was originally published on Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

© 2009 Denshō