During World War II, the Japanese residing in Peru were victims of numerous forms of abuse. The worst of those was their deportation to the Crystal City concentration camp in the United States. Below are the testimonies of two Nikkei who were there and now tell their stories .

Between 1942 and 1945, the governments of the United States and Peru worked jointly to send nearly one thousand Japanese and Nisei settled in Peru to concentration camps on American territory. Prosperous immigrants who paid their taxes—many of those married to Peruvian women—were imprisoned in the concentration camp of Crystal City, Texas, while in Peru their properties and businesses were seized by the government.

The rationale was simple. The United States needed prisoners who could be exchanged during World War II, and since they could not detain the Japanese residing legally in their country, they set their sights on the Latin country with the largest percentage of Japanese immigrants: Peru.

Sixty-six years later, two survivors explain what really happened during that dark and shameful period that changed their lives forever.

Augusto Kague was only 8 years old when the police took his father. They lived in Piura, where his family owned a restaurant. One morning, little Augusto went out to buy rice at his father’s request and upon his return his father was gone. For three months the family was kept in the dark, as the authorities provided no explanation for his disappearance. They expected the worst until a letter arrived. In it, his father explained that he had been detained and taken to the United States.

“The letter was filled with blotches that prevented us from reading certain words and even whole sentences. It had been censored. We replied to him and for two years we continued to receive his censored letters. During those two years my father’s business went bankrupt without him. There was no one to take care of it and soon we began living in destitution. They kicked us out of the house that we rented because we were unable to pay, so we began wandering like gypsies, living in the homes of friends and relatives.”

The situation became increasingly worse until an opportunity arose. A friend of his mother’s, whose husband had also been sent to the U.S., received an invitation to go with her children to live in the concentration camp. She didn’t want to go because her children were already grown and they were doing well in Peru. For that reason, she gave the letter to Mrs. Kague so that she, along with her 8 children, could go see her husband.

And that’s what happened. They petitioned at the Spanish embassy, which at that time served as an intermediary, the right to travel to the United States. In a few days, they sailed from Talara. The voyage lasted 20 days. The men traveled in the lower section of the boat while the women and children were gathered in the upper section. Every week the men were allowed to go up for 15 or 20 minutes so they could take walks and smoke a little. “Some would even put three cigarettes in the mouth at one time and then would smoke them,” remembers Kague.

When they arrived in New Orleans, they were required to take off their clothes. The fear of death took hold of each one of them. Then the American officials began to spray insecticide and detergents on them. “We were received as if we were animals infected with something,” Kague, visibly upset, remarks.

On December 7, 1941, Germán Yaki was 10 years old and was walking next to his dad and mom in the streets of Lima. They suddenly realized that something strange was happening. People were staring at them. It had to be a coincidence, as block after block people turned around to look at them, some with distrust while others were scared. When they arrived home they heard on the radio that Japan had attacked the military base in Pearl Harbor.

A couple of months later, Germán Yaki was playing on the street when he saw a truck go by carrying a group of Japanese men inside. One of them threw a coiled piece of paper at him. Yaki opened it. It was written in Japanese. He took it to his dad, Sentei Yaki, who saw that it was a goodbye message from one of the prisoners who had not been able to speak with his family. Sentei made sure the message reached the detained man’s family. From that day on, Yaki sensed that the same could befall his dad. And that’s what happened.

They went looking for him at his own home. They took him away without any explanations although Sentei Yaki was aware of what awaited him. Sentei’s wife brought him some clothes and then they didn’t see each other again. Six months later, Germán and his mother received a letter granting them permission to go live in the concentration camp.

Life in Crystal City

The black list containing the names and addresses of those who had to be detained had been jointly developed by the United States and Peru. The Peruvian government deported 1,771 Japanese and Nikkei to American concentration camps.

Life in Crystal City lacked freedom. The area was surrounded by a fence that prevented the possibility of leaving. “At each hour there were cowboys with rifles and horses patrolling the area,” says Yaki.

Crystal City was located in Texas and had many prefabricated wood houses. They were small buildings where the interned foreigners lived. The bathrooms were public and each family had to rotate the use of these services.

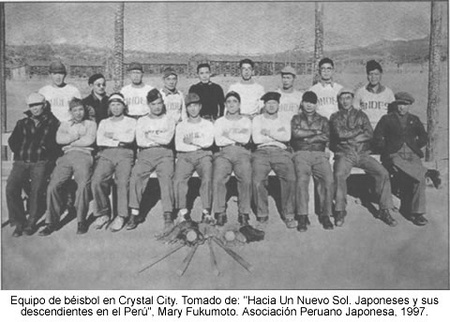

On the southern tip of Crystal City there was a hospital and on the northwest corner a baseball field. To the east, there were the prefabricated houses. To the southeast there was a kindergarten where English was taught.

The internees worked on the maintenance of the concentration camp. All of them earned the same amount: 10 cents per hour. This totaled less than a dollar a day.

In Crystal City they relied on a certain type of currency. People used it to conduct commercial transactions. Some of the coins had inscribed on them what could be bought, so that people couldn’t choose for themselves.

One morning, the fire alarm sounded. The internees thought that some of the houses were on fire, but they quickly realized what was going on. It was announced in both English and Japanese that Japan had surrendered and had lost the war. Some received the news with relief, thinking about their imminent freedom. Others refused to believe that Japan had lost and called the news an American lie.

A couple of days later an official notice was sent out announcing the end of the war. At that time, they began asking the internees where they wanted to go, whether Peru or Japan. The majority returned to Peru, while others opted to remain in the United States. Nobody wanted to return to the country that had lost the war.

The return trip was slow. Little by little. Many remained in the concentration camp for years after the end of the war. Also, those returning to Peru had to do it by way of the Talara port, for the United States didn’t want to spend extra money taking them to Lima.

The indemnification that doesn’t arrive

The financial compensation from the American government hasn’t been equal, much less adequate. Twenty thousand dollars were given to each member of families that had been deprived of their freedom. But this money was handed only to those who remained in the United States; not to the ones who returned either to Japan or Peru. Those who returned were offered only five thousand dollars.

“We protested that they should compensate us equally, but we haven’t had any success. Unfortunately, there was no solidarity and most of those that had returned accepted that amount. We continue our protest, but it is difficult because we don’t have a lawyer there,” says Germán Yaki, who, now 77, has begun losing hope of seeing that money someday.

There’s another aggravating factor in regard to the discrepancy in the compensation. Following their release, many families that remained in the United States were frightened by the authorities who told them that they were there illegally and would be expelled. They were told to leave the country and return legally.

“The families who followed that advice were deceived because when they requested their indemnification they were told that they were there of their own volition, that they had their papers and couldn’t ask for any sort of compensation,” explains Kague.

Neither Yaki nor Kague has received any sort of compensation or apologies. On the other hand, those residing in the United States, in addition to damages, have received a personal letter from President Bill Clinton apologizing for the treatment accorded them.

Although the American government has recognized its error and has apologized for the kidnappings of Japanese-Peruvians from 1942 to 1945, the Peruvian government has not only remained silent but has also failed to compensate the victims. Meanwhile, the years go by, seemingly judging against those who only hope for justice and an apology.

* This article was published thanks to an agreement between the Japanese Peruvian Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. It was originally published in the magazine Kaikan , issue 36, August 2008.

Text © 2008 Asociación Peruano Japonesa & Daniel Goya Callirgos; Photos © 2008 Asociación Peruano Japonesa