Manzanar Relocation Center, in Owen’s Valley, California, is unique among relocation centers for the number of community gardens that were designed and built by the internees during their incarceration. Most of the community gardens were built adjacent to residence block mess halls (hence their popular name: mess hall gardens) to help people pass the time as they waited in line to be fed. Over the past 14 years, the National Park Service has been clearing these gardens of debris and making them accessible to the public.

To date, five gardens have been cleared, and are the most prominent features within the camp’s internee residence area at Manzanar. Through historic documents, such as the Manzanar Free Press, most of the names of the individuals who built these gardens have come to light. We are also fortunate to have a few historical photographs that allow us to see what these gardens looked like in their full glory when they were planted with flowers and grass and the ponds sparkled with water.

I first started working at Manzanar National Historic Site in 1993, before the property was actually transferred to the National Park Service (NPS). As an archeologist with the NPS, I was part of the initial effort to identify and record what remained of the camp. This information would come to help the NPS in their management, interpretation, and preservation of the camp.

Today, as in 1993, the most prominent features at Manzanar are the entrance rock garden and sign, the two stone sentry buildings, the auditorium, and the cemetery monument.

What was found during those first days at Manzanar were mainly the remains of the long dismantled barracks and other wood-framed buildings: concrete slabs and foundation piers, nails and pieces of milled lumber; rock alignments lining foot paths and barrack entries, and the remains of gardens with concrete and rock-lined ponds.

Occasionally concrete features were found that were designed to look like tree limbs, logs, or sawn wood planks. The concrete was stained a reddish color and incised with lines to imitate wood grain. I became fascinated with these unusual creations, and as the days passed these faux wood (also known as Faux Bois, the art of molding and sculpting natural looking wood textures in concrete) features were found all across the camp.

Eventually the person responsible for these wonderful faux wood creations was identified. His name was Ryozo Kado, an Issei from Shizuoka-ken, Japan, who came to the U.S. in 1910. Kado was both a gardener and a rock mason.

At the time of our initial survey it was obvious that Kado’s work was special, but what I didn’t know was that we had discovered a true master of concrete and stone. As I would learn, Kado was responsible for most of the iconic features at Manzanar. In the 16 months that Kado and his family were at Manzanar, he created, among other things, the camp’s entrance rock garden and sign, the two rock sentry buildings, and the cemetery monument. Faux wood was Kado’s hallmark, and he incorporated faux wood features in the design of the sentry buildings and cemetery monument. He is responsible, probably more than any other individual, for the appearance of the camp today.

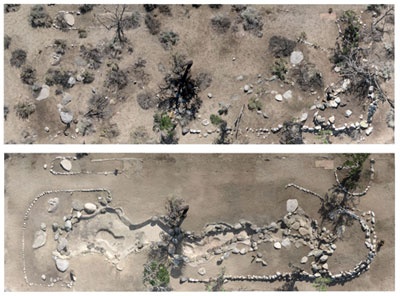

In 2007, the NPS decided to expose the garden in Block 9. This would be the fifth landscape or “mess hall” garden at Manzanar to be cleared for interpretive purposes. A small exposed portion of a faux wood tree limb had led us to believe this garden was the work of Ryozo Kado, and this was later confirmed by an historic document. Most of the Block 9 garden was covered by sand, and the true nature and extent of the garden would come as a real surprise. Working with volunteers, we slowly exposed the rock and concrete that was hidden from view for more than 60 years. When the garden was finally cleared we found it was the most complex mess hall garden at Manzanar. To our surprise and pleasure, there wasn’t just one faux wood tree limb, but there were nine, and they outlined two ponds.

I’ve always had a personal interest in water gardens, so the remains of the ponds at Manzanar have fascinated me. And as luck would have it, it has been my responsibility over the years to document the gardens for the National Park Service. For each garden, every rock, piece of concrete, tree stump, and mound of earth has been carefully mapped and photographed.

But the gardens are more than just concrete and stone monuments to a sad period of American history; they are the legacy of real people. The real story is that of the men who created these masterpieces that made a harsh place more endurable.

As already described, one of the garden designers was Ryozo Kado. With help from Japanese American National Museum Senior Research Assistant, Marie Masumoto, and park personnel, we are learning more about the man and his life beyond Manzanar.

I came to find out that his creations at Manzanar were not isolated instances of creativity. Kado actively designed and built gardens for many years before his forced relocation to Manzanar, and he continued to do so for many years after the end of the war. In 1946 he began working for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles; he was in charge of landscaping. He stayed with the archdiocese until his death.

As part of my research, I wanted to visit some of Kado’s extant gardens. In June of 2007, I made a trip to Los Angeles coinciding with the National Museum’s opening day of the exhibition “Landscaping America: Beyond the Japanese Garden.”

Since many of Kado’s works are in Southern California, Marie Masumoto and I visited the St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Altadena, California. There, almost 70 years ago, in 1938, he created his first major Catholic shrine. Called “Lourdes of the West”, the shrine is a grotto inspired by the famous grotto Our Lady of Lourdes in France.

Marie Masumoto and I were taken by the beauty of the grotto, but our attention immediately focused on the extensive faux wood features in and around the grotto. Faux wood was something we had only seen at Manzanar, but here there were faux wood furniture, tree stumps, and a faux wood fence. We also found a faux wood pulpit in the form of a large tree stump. All made from cement and wire mesh.

Later that day we drove to Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City. Kado began his work at the cemetery in 1946. To our amazement Kado’s work was everywhere. Dozens of faux wood trash containers, in the form of tree stumps, lined the streets; there is a large pond with extensive rockwork and faux wood tree limbs, logs, and stumps; and his most spectacular work: a huge Lourdes inspired grotto. The grotto is 30 feet high, with a 400 foot long rock wall with a water feature and many faux wood logs and stumps.

Ryozo Kado passed away in 1982, at the age of 92. He and his wife Hama are buried in the shadow of this amazing monument, a monument to his Catholic faith and to his creativity. (The Kados are in good company. There are a number of Hollywood celebrities buried near the grotto, and in fact Bing Crosby and Bela Lugosi lay only yards away from the Kados).

Kado’s abilities and creativity had always been known and recognized by the community in which he lived and worked. We did not discover a creative master, but re-discovered the man. Through his work at Manzanar, we have, and others will, rediscover the man and his creativity.

There are at least 13 other individuals who were responsible for the many landscape gardens at Manzanar. For me, their stories are just now starting to unfold. It is an exciting endeavor as I re-discover the lives and legacy of these Japanese Americans. It is a privilege and honor to be able to share their stories.

The effort to document the gardens and those who created them continues. In fact, it has really just begun. I am currently in the process of collecting information on the 14 men we know worked of the landscape gardens at Manzanar and I hope to identify others who also worked on the gardens.

The names of known gardeners and the gardens they worked on are:

Ryozo Kado - Hospital garden, gardens in Blocks 6 and 9

Cherry Park: Manjiro (William) Katsuki

Block 34 garden: George Murakami, Goichi (George) Kubota, Seiichi Kayahara

Merritt Park: Kuichiro Nishi, Takio Muto

Block 4 garden: Mokutaro (Mark) Nishimura, Chotaro Nishimura

Hospital garden: Nintaro Ogami, Bunyemon Wada

Block 22 garden: Harry Ueno, Saburo (George) Takemura, Akira Nishi

If you have information about any of the individuals listed above, other people who worked on the gardens at Manzanar, or have photographic images of the gardens and would like to share this information, please email Ronald Beckwith at ronald_beckwith@nps.gov, or contact Manzanar National Historic Site at www.nps.gov/manz.

The park plans on cleaning up Merritt Park in the spring of 2008. If you are interested in this project or other volunteer opportunities in 2008, please contact the park.

© 2008 Ronald J. Beckwith