>> Rear part 1

Formal Education: Catholic Schooling

Kurihara was born in 1895 on the island of Kaua‘i, in what is now the state of Hawai‘i. His parents were among the 180,000 Japanese who journeyed to the islands from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, most of them having been recruited to work on the islands’ sugarcane plantations. (About half of the Japanese recruits eventually settled in Hawai‘i, while the other half either returned to their homeland or moved to the continental United States.)1

When he was eight years old, Kurihara, like his four siblings, began attending public grammar school. Several years earlier, his family had moved to the island of ‘Oahu and settled in Honolulu. Kurihara completed the eighth grade at the age of sixteen. Then in 1913—after a two-year period of working to earn enough money to continue his schooling—he entered St. Francis School as a first-year (9th grade) student. The school was an all-male Catholic charity school, attached to the prestigious St. Louis College, a high school run by the Brothers of Mary.2 The tuition at St. Francis was either fifty cents or a dollar a month, depending on the student’s financial circumstances. A few students, Catholics more readily than non-Catholics, were granted waivers. Kurihara paid a dollar each month.3

Although Kurihara could have attended McKinley High School, a tuition-free public school with high standards and accessible by trolley car, he chose instead to attend a Catholic high school. By then he was attracted to Catholicism, and attending St. Francis School brought him closer to the religion of his choice. While his courses included English, algebra, U. S. history, shorthand, bookkeeping, and elocution, they also included lessons in manners and morals, as the Brothers did not refrain from proselytizing their non-Catholic students. Catholic students, of course, took religion courses, but even non-Catholics like Kurihara enrolled in ethics classes in which they received a strong dose of Catholic teachings. His teachers were most concerned with “character formation,” viewing their task as not so much to “instill knowledge but to make good men.” With this emphasis on morals and religion, St. Francis School, like St. Louis College, succeeded in converting many of its non-Catholic students. In 1913-14, when Kurihara was at St. Francis, about thirty boys at the two schools were baptized. Although Kurihara was not one of them, his classmates who converted made an impression on him, for immediately after relocating to San Francisco, he was baptized.4

The Marianists who taught at St. Francis School internalized the idea articulated by Father Chaminade, who in 1817 founded their order, the Society of Mary.5 The idea was that graduates of their school would be instilled with the ideals of “liberty, equality, and fraternity in the Christian [non-violent] spirit.”6

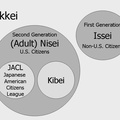

Kurihara’s attraction to Catholicism was an anomaly in his family and among the Nikkei. Among his family members, who were Buddhists, he was the only one who attended Catholic school and converted to Catholicism. And historically, most Nikkei who became Christians chose Protestantism.7

In his class of forty-six students, he was the only Nikkei. By comparison, Chinese Americans, who had migrated to the islands a generation earlier than the Japanese and were more open to Christianity, constituted 44 percent of his classmates, while European Americans made up 37 percent, and Native Hawaiians 17 percent. This ethnic make-up of his class reflected the student population at St. Francis School, St. Louis College, and the rest of the Catholic schools in the Territory of Hawaii.8

Attending St. Francis School for a year convinced Kurihara that a Catholic education suited him. He decided to continue his schooling in California, where he would pursue his ambition to become a doctor. Since his family could not afford to support his educational aspirations, Kurihara took a temporary job in road construction; this enabled him to earn as much as he could within a short period of time. In July 1915, he left Honolulu aboard the steamship Sierra.9

Soon after arriving in San Francisco, Kurihara joined the St. Francis Xavier Japanese Catholic Mission, located in the “Japan town” section of the city. The mission served as a sanctuary for Nikkei Catholics in San Francisco. Like other Nikkei on the West Coast during the 1910s-30s, those in San Francisco faced anti-Asian hostility; even among white Catholics, there was an “intense racial prejudice and hatred of Asians.” In such an atmosphere, the St. Francis Xavier Mission in San Francisco was a place of both refuge and spiritual sustenance.10

Named after the Jesuit priest who in 1549 had led the first Christian missionaries to Japan, the San Francisco mission had been established in 1913 as part of the effort of the Maryknoll Catholic Foreign Mission Society to open schools and minister to the spiritual needs of Japanese Catholics along the West Coast. Father Albert Breton, who had previously lived and worked in Japan, began this effort by opening a mission in Los Angeles, and the following year, opening the another in San Francisco, naming both after St. Francis Xavier.11

In 1914 the Society of Jesus took over responsibility for the San Francisco mission. Father Julius von Egloffstein, who headed it, had previously served in Japan as a missionary and was thus familiar with the customs of the Japanese community. In November 1915, he baptized Kurihara, who took the name Joseph, appropriate for a Catholic, with a similar-sounding first syllable as his birth name, Yoshisuke.12

NOTES:

1. Eileen H. Tamura, Americanization, Acculturation, and Ethnic Identity: The Nisei Generation in Hawaii (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 27. About 400,000 migrants, most of them from Asia, Europe, and the South Pacific ventured to the islands before World War II, about half of whom settled there. See Andrew W. Lind, Hawaii’s People (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1967), 8.

2. Reginald Yzendoorn, History of the Catholic Mission in the Hawaiian Islands (Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1927), 230; Patricia Alvarez, “Weaving a Cloak of Discipline: Hawaii’s Catholic Schools, 1840-1941,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawaii Manoa, 1994, 244, 265, 382.

3. Alvarez, “Weaving a Cloak of Discipline,” 252; S.F.S. #1, Bro. Leo Schaefer, 1913-14, “Tuition Records 1912-1916, St. Louis College and St. Francis School,” File 307, SLC Records, St. Louis School Archives, Honolulu, hereafter SLC Records.

4. Alvarez, “Weaving a Cloak of Discipline,” 241-42, 291-92, quote from 207; conversation with Patricia Alvarez, 7 June 2007; Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara, Certificate of Baptism, San Francisco, November 16, 1915.

5. Joseph J. Panzer, Educational Traditions of the Society of Mary (Dayton, OH: The University of Dayton Press, 1965), 8-10.

6. Alvarez, “Weaving a Cloak of Discipline,” 287-88; conversation with Patricia Alvarez, 7 June 2007.

7. In an examination of the religious affiliation of the Nisei in the greater Seattle area, Stephen Fugita and Marilyn Fernandez found that only 8 of their 183 survey participants were Catholic, while 66 were Protestant and 54 were Buddhist. Fujita and Fernandez, Altered lives, Enduring Community: Japanese Americans Remember Their World War II Incarceration (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004), 233 n2. These data, while collected in the 1990s, help to explain the lack of discussion of Catholics and the tendency to combine them with Protestants in publications discussing religious affiliations among Japanese Americans before and during World War II. See, for example, David Yoo, “A Religious History of Japanese Americans in California,” in Religions in Asian America: Building Faith Communities, ed. Pyong Gap Min and Jung Ha Kim (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2002), 121-42; Edward K. Strong, Japanese in California, Based on a Ten Percent Survey of Japanese in California and Documentary Evidence from Many Sources (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1933), 352-59, 382; and Dorothy Swaine Thomas, with the Assistance of Charles Kikuchi and James Sakoda, The Salvage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), 66-69, 607.

8. S.F.S. #s 1-4, 1913-14, “Tuition Records 1912-1916,” SLC Records; St. Louis Term Report, December 1913, Department of Public Instruction, Hawaii Territory, Hawaii State Archives, Honolulu; Yzendoorn, History of the Catholic Mission in the Hawaiian Islands, 239.

9. Kurihara left St. Francis School in March 1914. Class Register September 1913 to March 1914, Brother Leo, Class Registers 1904-1916, First Class St. Francis School, File 140, SLC Records; S.F.S. #1, Bro. Leo Schaefer, 1913-14, “Tuition Records 1912-1916,” SLC Records; Kurihara, “Autobiography,” 1; Manifest of Alien Passengers from U.S. Insular Possessions, manifest no. 14498, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1410 (Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, 1 May 1893-31 May 1953), Roll 83, National Archives Pacific Region, San Bruno, CA.

10. For anti-Asian hostility, see Roger Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962), 33-34; Charles M. Wollenberg, All Deliberate Speed: Segregation and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855-1975 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 53; Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 29-66, 100-154; Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991), 45-61. For anti-Asian hostility among Catholics, see Jeffrey Burns, “Building the Best: A History of Catholic Parish Life in the Pacific States,” in The American Catholic Parish, vol. 2, ed. Jay Dolan (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 72. Quote is from Burns, “Building the Best,” 72.

11. “Xavier, Francis, St.,” New Catholic Encyclopedia, v. 14 (Detroit and Washington, D.C.: Thomson/Gale and Catholic University of America, 2003), 877; Yuki Yamazaki, “St. Francis Xavier School: Acculturation and Enculturation of Japanese Americans in Los Angeles, 1921-1945,” U.S. Catholic Historian 18, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 56-57; Kyoko Matsuki, “Golden Era of Our Church,” unpublished typescript, St. Francis Xavier Japanese Catholic Mission, 1992, 1-6. Breton also helped lay the groundwork in 1916 for Our Lady Queen of Martyrs parish in Seattle. See Madeline Duntley, “Japanese and Filipino Together: The Transethnic Vision of Our Lady Queen of Martyrs Parish,” U.S. Catholic Historian 18:1 (Winter 2000): 73-98. For discussions of the San Francisco Japanese community in the early decades of the twentieth century, see Suzie Kobuchi Okazaki, Nihonmachi: A Story of San Francisco’s Japantown ([San Francisco]: SKO Studios, 1985), 38-82; Kenji G. Taguma, “San Francisco Japantown Properties Up for Sale,” The Hawaii Herald, 27: 6, 17 March 2006, 1, 26. The mission was located on 2011 Buchanan Street; in the few months before he left San Francisco, Kurihara lived within a block of the mission, at 2041 Pine Street.

12. Information on Father Egloffstein is in Catalogus Provinciae Californiae, Societatis Jesu, 1915, p. 21, RG 1 Box 19, University of San Francisco Archives. The Society of Jesus led the San Francisco mission from 1914 to 1925; then it was transferred to the Society of the Divine Word. See John Bernard McGloin, Jesuits by the Golden Gate: The Society of Jesus in San Francisco, 1849-1969 (San Francisco: University of San Francisco, 1972), 182-83. The records at St. Francis School in Hawai‘i has Yoshisuke as Kurihara’s given name. His certificate of baptism and the records at St. Ignatius School identify him as Joseph Y. Kurihara. See Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara, Certificate of Baptism, San Francisco, November 16, 1915; and Registrar’s Book, 1906-1927, St. Ignatius High School, RG1 Box 17, University of San Francisco Archives.

*This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

**The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society