I. Matsuri in Overseas Nikkei Communities

Today, overseas Nikkei communities celebrate traditional matsuri (Japanese festivals) under two types. The public space type is held outdoors in a public space or in the streets. The theatrical type is performed on a stage in a theater or hall.

Public space type festivals are usually held in areas where Japantowns once thrived. These events often feature outdoor taiko performances and street dancing called ondo. But, there might also be flower arranging or calligraphy exhibitions held indoors, as well as dance or theater performances on a stage.

Matsuri first started for many reasons, but today, the focus of the matsuri is to revitalize Japantowns as the spiritual hometown for Nikkei communities. In other words, as Japantowns get smaller or in some cases disappear altogether, the matsuri is one way that communities have responded to such a decline. Events that fall within this category include the Los Angeles Nisei Week Festival (United States), founded in 1932; the São Paulo Sendai Tanabata Matsuri (Brazil), founded in 1972; and the Powell Street Festival (Canada), founded in Vancouver in 1977.

Theatrical type festivals may consist of singing competitions for kayo (popular songs) and minyo (folk songs). The singing competitions start at the city level and advance to the state and national levels. Within the Nikkei community, participants sing for fun or as a hobby. Singing competitions make up the most common type of cultural event.

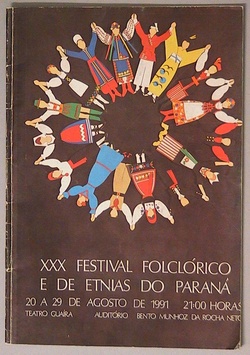

Another kind of theatrical type festival is the folk art festival co-organized with other ethnic groups. This reflects the multicultural makeup of societies in places such as Brazil and Canada. These festivals are places for introducing each ethnic group’s folklore before an audience. For Nikkei, these events serve as places where they can express their ethnic identity. Examples of such events include the Paraná Folklore and Ethnic Festival in Curitiba (Brazil), founded in 1958, and the Folklorama Folk Festival in Winnipeg (Canada), founded in 1970.

An example of the relationship between the Nikkei community and Matsuri is the Paraná Folklore and Ethnic Festival in Brazil.

II. Paraná Folklore and Ethnic Festival

Usually Brazil conjures up such images as soccer, samba, Carnival or the Amazon. But in the three southern states, the active influx of immigrants and a remarkable cultural difference from other regions is easily observable. One of these states, Paraná, has seen the largest number of immigrants and there are now around sixty ethnic groups. As a result, the state capital Curitiba has been nicknamed “the ethnic laboratory” due to the diversity of its residents. An advertisement for the Paraná State Bank reads: “Somos tantos mas somos um. Somos o Paraná de todos os povos” (There are many kinds but we are one. Paraná belongs to all peoples). This demonstrates how this state is a typical immigrant state. And today, one event that brings to the fore the presence of such immigrants is the Paraná Folklore and Ethnic Festival.

The Folklore and Ethnic Festival started in 1958 at the suggestion of the wife of the Dutch consul general as a philanthropic project. However, since there were few forms of entertainment at the time, the response was huge. A well-known magazine wrote a piece on it and the state government also became a supporter. Every August for the ten days around Folklore Day, the state theater was packed with performances.

In 1974, when the Paraná Interethnic Association was established, an effort to jointly preserve cultural traditions emerged, and each group began supporting the festival as a site where they could share their cultural traditions with the next generations. At present, the eight different ethnic groups with the longest history in the area serve as the core, and each group is allotted two hours in which to perform such things as ethnic dance and music. The festival also serves as a stage for competition among the various ethnic groups.

III. From an Insider Event to an Inclusive Event

During the time when Japanese immigrants created communities in remotes areas, they held summer festivals and Bon odori just as they had in their villages in Japan. The festival, where community members helped each other and prayed and celebrated together, was an indispensable ritual for these communities far from their home country. In some of the rural farming communities that still exist, these festivals are held in much the same way they were back then.

However, many of these were insider events—something for members of the ethnic community to enjoy among themselves, where enjoyment alone was sufficient. Both performers and viewers were Japanese, and enjoyment itself—the festival itself—was the goal of the event.

But now, the circumstances that surround such matsuri have changed dramatically. Almost all of the festivals organized by Nikkei are held for non-Nikkei as well, so that they transcend the ethnic community and are organized for everyone. As a result, these events move beyond simple self-satisfaction and enjoyment, but have become events for the outside. Prominent features of today’s matsuri are getting non-Nikkei to understand the festival’s intent and contents and encouraging others to participate. In essence, the matsuri has the important purpose of introducing Nikkei culture to the general public.

The Folklore and Ethnic Festival is no exception. In the beginning, the principle participants were those with an interest in folk songs and dance, with their concerned people attending as observers. But now these are no longer just annual rituals within the community, they are important opportunities to contribute to society by sharing culture with others.

Festival preparations take place throughout the year, with training scheduled at least every weekend, sometimes even several times a week. As part of this process, each art form performed during the matsuri has become more authentic and formalized. Literally, this represents the emergence of the shishou (master teacher). Until this time, a teacher was selected from among the members of a group, but things changed so that groups began to receive instruction from masters who had undergone training and been credentialed in Japan. These are natori, masters of Japanese dancing and shihan, masters of Japanese popular songs.

Also, in terms of costume and equipment, initially people made them from local materials and used the same things year after year, but later they started to order costumes from Japan. These costumes were more expensive and extravagant, but nonetheless from the homeland.

For performers, regular training and discipline became even more essential, and the financial burden also increased. In this way, with a clear goal in mind, these performances required an even more dedicated effort. For many Nikkei, however, this extra effort has become very rewarding.

Furthermore, for young Sansei, these performances serve as opportunities for them to boldly display their Nikkei identity publicly on stage.

IV. Matsuri as a Way of Preserving Community

With increased diffusion of Nikkei into the host society and with its borderless tendency, young Nisei and Sansei began to place some distance between themselves and the Issei-centered communities, resulting in the progressive decline of traditional Nikkei communities. As a result, Nikkei solidarity and the precious inheritance of Japanese culture have not been passed on, and a sense of crisis is emerging from within the respective communities that the community itself will disappear.

As a way of stopping this process, Japanese language education was the first approach attempted in the countries where Japanese have emigrated. In order to bring along successors of the Nikkei community, it was necessary to get them to understand Japanese culture, and for this to happen, it was thought that Japanese language learning was a necessary first step. However, in reality, while it was possible to implement Japanese language education as long as children were young and obeyed their parents, once children entered high school, unless they had some special motive or reason to continue studying, most quit. On top of this, participation by younger members of the community also declined at events held in the Nikkei community. In the face of such events, leaders of Nikkei communities in different areas felt a sense of crisis, and worked on coming up with different ways of finding a resolution.

With the Folklore and Ethnic Festival, it became clear since the 1980s that the number of participants was decreasing. Nisei and Sansei leaders began to feel gravely concerned for the future of the Nikkei community. Up to the first half of the 1990s, the majority of participants in these events were middle-aged Nisei women or elderly Issei immigrants. Issei felt nostalgic for Japan. They were comfortable with singing and dancing and felt a natural affinity for folk arts.

At “bunkyo” events, the typical scene was a gathering of elderly Issei and Nisei. Women took lessons in Japanese dancing. Some kenjinkai (prefectural association) members practiced singing regional folk songs accompanied by the samisen or shakuhachi (vertical bamboo flute) and others practiced karaoke.

(“bunkyo” -- this is the abbreviation for bunka kyokai, or cultural associations, that oversee all of Nikkei organizations. In Brazil, it is common practice for the names of such organizations to be “bunka kyokai” preceded by the region name, and in general they are referred to in this abbreviated form)

For example, the Japanese Brazilian Cultural and Beneficent Society in Curitiba has created a cultural hall and a sports club in the central part of the city as well as in the suburbs, and such sights could be seen at these facilities on a regular basis. However, it was rare to see children at these places. Children could be seen playing baseball on the field next door, or enjoying themselves in the pool, but they were never seen with the elderly. The immigrant Issei may have wanted to speak to their grandchildren in Japanese, but in actuality, the two generations had very little in common to bring them together. And Sansei were rarely seen attending performances put on by Issei who had prepared with much practice.

However, as community activities decreased and with it cultural knowledge as well, a bright idea formed. The idea was that perhaps the matsuri could be the thing that would provide an appropriate site for Sansei grandchildren and Issei grandparents to be in the same place at the same time. These grandchildren could learn something from grandpa and grandma. In other words, if they could practice singing, dancing, and playing musical instruments together, there would be greater opportunities for inter-generational contact and relationships. This could lead to the sharing of values and ideas, as well as a greater sense of group identity and solidarity.

Community leaders proposed many creative ideas in order to encourage children and young people to feel some kind of interest in Japanese culture. From “spring matsuri” to “sushi matsuri” to “immigrant matsuri,” many different kinds of matsuri were planned one after the other. These not only helped to introduce everything from food culture to traditional Japanese culture to the history of Japanese immigration, but these events were used as sites for traditional dance and song performances. Eventually the Folklore and Ethnic Festival became the annual maximum event where all of these groups performed.

Among such activities, karaoke was one that worked particularly well. Karaoke was popular not just among Issei, but among Nisei and Sansei as well, so that all, regardless of generation, could practice together. Also, karaoke sung by Nikkei abroad differs in meaning from that sung by Japanese in Japan. Before karaoke, songs were played on record players or sung by parents and grandparents in immigrant communities located in remote areas. For Nisei and Sansei, the experience of seeing their parents cry while listening to these songs is not simply a nostalgic and bittersweet memory of childhood, these songs brought back a sense of identification with their parents and relatives. And even if they couldn’t understand the meaning of the lyrics, karaoke connected them to a common sense of identity as Nikkei. Even after the karaoke fad had faded in Japan, karaoke continues to be popular in overseas Nikkei communities.

One example of the meaning of karaoke is the story of two Sansei cousins who in their late teens started participating in the Folklore and Ethnic Festival. In their childhood their grandfather influenced them by singing Japanese songs. They started attending a kayo kyoshitsu (Japanese popular song class) as a result. They couldn’t understand the meaning of the songs, but they sang in Japanese. The teacher told them that singing folk songs would help their vocalization and expression when singing popular songs, so they learned folk songs as well. Soon they began entering karaoke contests. If they were able to take first place they would be given the opportunity to travel to Japan. As they began to appreciate the content of the music, they also began entering folk singing contests. When they trained folk songs at the cultural halls, they saw Issei playing samisen, so they began to be interested in samisen as well. This, in its turn, led to an interest in Japanese dancing.

Through such contact, their view of the world of Japanese culture expanded, and as they became more knowledgeable about related fields, they found that things written in Portuguese were insufficient for them, so that they finally felt the necessity of learning Japanese. In other words, they started with an interest in music and instruments and dancing, and as they pursued such arts, they were faced with the importance of learning language.

This episode speaks of the necessity for learning Japanese in order to maintain Japanese culture in Nikkei communities, but it also provides an important hint as to how Japanese should be taught, and how interest in Japanese can be encouraged. In other words, it is not that learning Japanese will lead to an interest in Japanese culture, but that through being introduced to Japanese culture and becoming interested in it, they will develop an interest in studying Japanese as well.

Karaoke practices are held often at cultural halls, and in Brazil, there are almost monthly karaoke contests at the regional, state, and national level. This is not simply karaoke for karaoke’s sake, but is a critical opportunity to encourage interest in Japanese culture among Nikkei.

In addition to karaoke, there is a need to create opportunities to involve Sansei in the artistic practices engaged by Issei and Nisei at the cultural association.

References

Akemi Kikumura-Yano, editor, Amerika tairiku nikkeijin hyakka jiten (Encyclopedia of Japanese in the Americas) (Akashi Shoten, 2002)

Imin Kenkyukai, editor, “Senso to Nihonjin Imin” (Toyo Shorin, 1997)

Harumi Befu, editor, “Nikkei Amerika Jin no Ayumi to Genzai” (2002)

Shuhei Hosokawa, “Sanba no Kuni ni Enka ha Nagareru” (Chuko Shinsho, 1995).

* This article was originally published in Nanboku Amerika no Nikkei Bunka (Jimbun Shoin).

© 2008 Shigeru Kojima