Among the remarkable generation of Canadian Nisei artists, there are names like Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994), Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002), Nobuo Kubota (1932– ), and Takao Tanabe (1926– ), among many others, who grew up during the internment years and gave expression to their personal experiences.

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC) in Toronto has recently been featuring work by an outstanding new wave of Nikkei artists, some of whom have introduced to Discover Nikkei readers already: Linda Ohama, Emma Nishimura, Kats Takata, and Hitoko Okada.

It is significant that these artists offer both intergenerational and cultural bridges to understand the ongoing evolution of our community and what we have become today. Just as writers like Lafcadio Hearn, Buddhist scholar DT Suzuki, novelist Jiro Osaragi, among many others, helped to bridge gaps of understanding for their respective generations, Mark Yungblut, a young kiri-e artist from Waterloo, Ontario, is helping to keep this continuum going for younger generations of Canadian Nikkei now too.

Recent works by the 33-year-old artist are being featured at the JCCC until August 16, 2015. (He is also conducting a kiri-e workshop there. See website for details.)

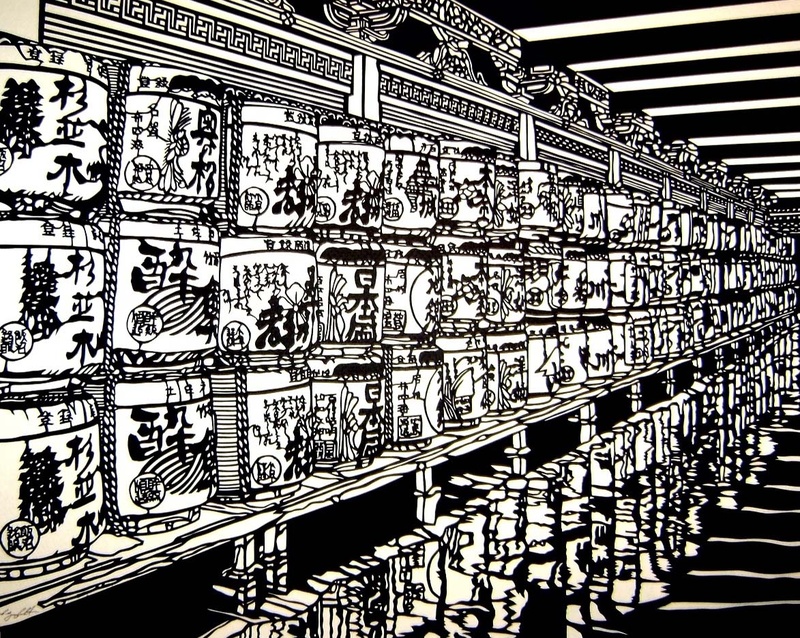

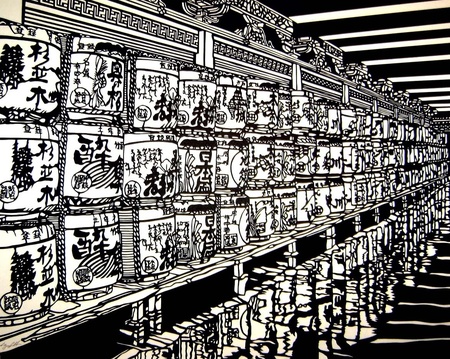

Describing the “Shodenzan Series” exhibition, Yungblut, one of Canada’s premiere kiri-e artists, explains: “The pieces I’ll be showing will all be depicting different scenes from a temple called Shodenzan in Menuma, Saitama Prefecture.

“Last year while we were in Japan, my family and I, along with my wife’s friend’s family went to briefly visit the temple complex because it is very close to their home. They decided to go for kakigori after a few minutes, but, as always, I couldn’t waste any seconds not looking around and taking pictures, even though I had been there several times before. What I didn’t know at that time was there was a whole section with a large pagoda and river that I had never seen before. I had wanted to make a series of art depicting this temple for a while but didn’t think there would be enough pictures to work from (especially since it’s been under construction for the past few years). This new portion gave me enough pictures to work from, and I really enjoyed working on this series.”

* * * * *

Can you describe your path to becoming an artist?

I was born in Hanover, Ontario. I moved to Regina, Saskatchewan when I was seven, and then moved back to Ontario to live in Mississauga at the age of 11. I lived there until I moved to Waterloo, Ontario to go to University in 2000 and have been living here ever since. I completed my B.A. and Bachelor of Social Work degrees in 2003 and 2004, and went back to university and received my Master of Social Work degree in 2012.

In terms of my path to becoming an artist, it was mostly by accident. In high school we were required to take arts courses, and because I was so shy I dreaded taking drama, so by default I enrolled in visual art class. I learned the basics the first few years but didn’t really enjoy it all that much until my last year in high school. I was writing an essay on Japanese history and came across a picture of Himeji Castle, and for whatever reason I felt impelled to draw it. It turned out really well, and after that most of my spare time over the next couple of years was spent drawing Japanese castles and temples.

When I first contacted, you made a point of telling me that you weren’t Nikkei. Where do you place yourself in relation to the Nikkei community? How much do you feel a part of it?

Yes, I honestly just wanted to make sure I qualified for being interviewed for this series!

That’s a difficult question that I’ve never really thought about consciously. It really depends on what you mean by Nikkei community? There is a Nikkei-kai association that we are a part of here in Kitchener-Waterloo. It is somewhat small given the number of Japanese people in K-W, but I definitely feel a part of that community.

There are a number of mixed marriages within the group, with many half-Japanese half-Canadian children. Because it’s such a small group there are no issues with not being of Japanese descent. If you’re asking about the larger Nikkei community, I suppose I do feel a part of it to a certain extent. Most Japanese people are intrigued by the fact that I do kiri-e and speak a bit of the language, so I think that helps bridge some of the gap. I recently learned that I’ve been placed on a list of “bunka-jin” (cultural person) for the Japanese embassies and consulates in North America, so I guess that counts for something. I think the fact that I’m so passionate about kiri-e, and that it isn’t just a fad or trend for me, allows people to know that I have a really deep appreciation for Japan, which is almost always greeted in a welcoming fashion.

What is your own family’s ethnic background?

My grandfather on my father’s side was born here after his parents immigrated from Germany. My father’s mother is of Scottish background. Her mother was born in England, her father was born in Canada. My mother’s parents were both second generation Canadian, with her grandparents coming from England.

So when did your attraction to “things Japanese” begin?

I started taking karate when I was 14 years old, but I didn’t really become fascinated with Japan until I was about 16 or 17. I’m not sure why, but I stumbled across James Clavell’s book Shogun, and for whatever reason I felt I had to read it. From there it just snowballed.

Can you give us a brief history of kiri-e? Can you describe your personal affinity for the art form?

At first I wasn’t all that concerned about the history of kiri-e, but I’ve become acquainted with many paper cutting artists across the world online recently, which has piqued my curiosity about the art form. There are many different styles, but I would say the type of paper cutting I do would draw its lineage from China. Paper cutting in China dates back about 1,500 years.

Most of what I have seen in traditional Chinese cut outs are two dimensional, focusing on animals and Chinese characters, and would be used for festivals, rituals, etc.

As far as I know it evolved in Japan out of “kiri gami”, which is a combination of origami and paper cutting. I believe it has become popular in many countries in Europe, South Asia, and Mexico. Some use scissors to cut paper, but I prefer a single bladed knife.

The style that Mr. Okamura teaches is almost exclusively in black and white. I’ve found that in North America people prefer the colour, while in Japan people are able to appreciate the black and white ones a bit more. Most Chinese paper cuttings that I’ve seen are done in red paper, with no other colour added. I think that this simple difference in preference says a lot about each respective culture.

Can you please elaborate about what this might say about Japanese and Chinese culture, respectively?

In terms of the way Japanese and Chinese cultures specifically are represented, I can only really speak to the works that I’ve seen, and some of the differences in culture I’ve noticed over the years.

As a general rule, I’ve found that Chinese people are a bit more direct and straightforward. They also have a tendency to be a bit more pragmatic in some ways. So in terms of subject matter, you see this art form used for practical purposes, i.e. decorations for celebrations. For example, if it’s the year of the dragon, you’ll see a lot of paper cuttings of dragons. In Japanese culture you tend to find a bit more subtlety and, for lack of a better term, concealment.

I think this plays out in the subject matter, as you find more abstract works or depictions of everyday scenery (people, architecture, plant life) that can hold within themselves a deeper meaning than meets the eye. In no way am I saying one style or use of paper cutting is preferential to another, but I find it really interesting how these differences play out organically, and will happen on their own over a long period of time.

Can you comment about your personal affinity for this art form?

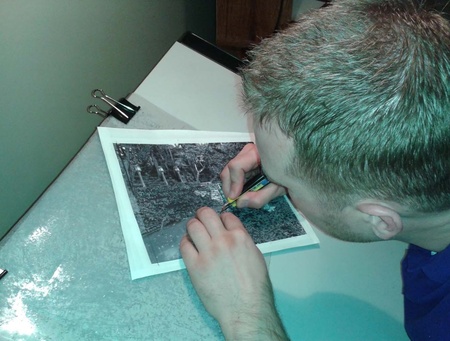

One of the reasons why I like this art form so much is because it presents such a challenge in terms of how to represent different subject matter. With a pencil you can essentially just start drawing. With this medium, in order to create an effective piece, you need to plan everything out before you start.

I often tell people the cutting is the easy part, as long as you have the patience to do it. The hard part is knowing where to put the lines that are going to be cut. You also don’t really have the option of shading, or any kind of gradation, so that’s another thing that needs to be figured out.

I also appreciate the finality of paper cutting. With pencil you can erase, paint can be painted over, but once you’ve cut the paper it can’t be undone. Again going back to the planning involved, this forces me to really think about what I’m going to do beforehand.

Up until the age of around 23, I would only draw in pencil. When I first tried out kiri-e I honestly didn’t like it at all. It was frustrating, in part I think because I didn’t have the right tools, but also because I didn’t see any reason to stop drawing in pencil. I didn’t think there was any advantage that this art form could give me that I couldn’t get using a pencil. I grew to like it after being given the proper tools by my teacher, Yasuyuki Okamura, and shown a bit more how to do it properly. I’m glad he was persistent in getting me to at least make a proper effort at doing it.

The art form seems particularly suited to representing things that are “Japanese”?

I think that may just be because the specific style I do was developed in Japan. I think if we really look deeply into it, there are some cultural elements that are reflected in this method, but I also think it has to do with our own understanding of what looks “right” based on what we’ve seen all of our lives.

I think painting seems more suited to North American and European scenery because that’s what’s been used to depict those subjects more often than not. There’s absolutely no reason why “western” style painting can’t be used to depict Japanese scenery, and why kiri-e can’t be used to depict western scenery, it just isn’t what we’re accustomed to seeing so it might look a little bit off at first. I’ve come to learn that the only limits to this art form (and I would say any other) are those that I put on myself. There’s no reason it has to be only one certain subject matter or done only one way. If there are boundaries, then it isn’t art.

Have you ever tried to take on Canadian themes using kiri-e?

I have made several Canadian-themed works. The only real challenge that I find when making kiri-e of any subject is to find the right picture to work from. Some pictures work for kiri-e, some don’t. That understanding only comes from experience and developing your own style.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki