Your art seems to focus on traditional aspects of Japanese culture like temples, shrines, cherry blossoms, etc. Is there a reason for this?

I’d like to give you a more in-depth answer than “because I like them,” but that’s essentially it. I really can’t explain why I’m so drawn to this subject matter, maybe I worked on their construction in a past life. I have been to several castles and temples, and the feeling I get while I’m there is unlike anything else.

Except for one trip, I’ve only ever been to Japan during August, the hottest time of year. My wife deserves a lot of credit for taking me to these places knowing she’s going to have to sit outside in 45 degree [Celsius] weather while I walk around taking pictures for 3-4 hours. If she weren’t there with me I’d probably never leave. Why I have such a strong connection to traditional Japanese architecture, I don’t know? But it’s there and it’s very strong.

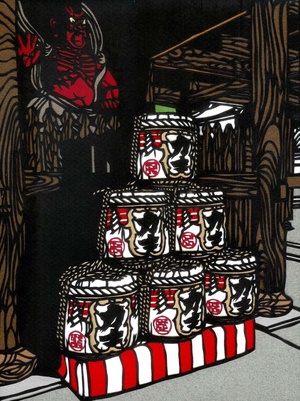

Whenever I’m creating art, the subject matter is being filtered through me. Sitting and interacting with this subject matter for hours on end is something I enjoy doing. By doing so I’m creating a real connection, and any time I go back to any scene that I’ve cut out, I feel a very strong connection. As you know, in the Shinto belief, every natural thing has a soul. Most of the older buildings are constructed out of natural material, so I think that connection is real.

Are your representations of these Japanese things different than how they are traditionally represented by Japanese kiri-e artists?

As far as I know, traditionally kiri-e was done in black and white, so that is one major difference. I have however seen a lot of newer Japanese artists use colour, which I would guess is just a matter of the availability of material more than anything else. In terms of how my artwork differs in style, it’s difficult to say. As I’ve said, every artist is different, so it’s impossible for two people to come up with the same finished product. I don’t know that there’s anything in the way I do kiri-e technically that would allow someone to know that I’m a non-Japanese artist, other than particular subject matter. I have seen a number of people very surprised at the fact that I’m not Japanese after they’ve seen my artwork.

Is there something about Japan that you are trying to capture about your subject matter for your Canadian audience then?

I wouldn’t say it’s limited to the Japanese subject matter I use, but overall I think that one thing an artist should do is find beauty or meaning in the seemingly mundane, or more broadly to appreciate the things we have around us a bit more.

As that idea relates to Japan, most of my audience has seen the more famous temples and typical scenery hundreds of times. So the challenging/fun part is finding scenery that is new and interesting to use in my artwork. Even if it’s something that is an everyday thing for Japanese, it isn’t so for people looking on from Canada. Visiting some of the smaller temples and shrines that I’ve been to, sometimes I get the impression that the people living around them take them for granted because they’ve seen them every day of their lives. Someone from another country might show a bit more interest because it’s such a different setting, and so rare for them to see.

It hasn’t really been until recently that I’ve come to realize how much I’ve been doing the same thing here in Canada. Because I’ve grown up with all of this unique scenery around me, it wasn’t until I began looking for Canadian images to use for my artwork that I realized how special some of these settings really are. I really only like to use my own photographs for my artwork, so I’ve had to force myself to stop and take notice of things that I simply haven’t analyzed before. For instance, I’ve begun using a lot more trees in my artwork recently, so I’ve had to really look closely at how light and shadow are affected by different sizes and shapes of leaves and trees. This isn’t something I would ever have appreciated if I didn’t use them in my artwork.

In April 2004 you went to Japan and learned kiri-e for the first time from Yasuyuki Okamura. Was that trip for that specific purpose? If so, how was it arranged?

My wife’s family still lives in Japan, and we go back to visit almost every year. She is from Kumagaya, Saitama prefecture. Her mother and sister still live on the same property where she grew up. That year, as with every other, the main purpose was to visit them. Meeting Mr. Okamura was strictly a stroke of luck/fate. Up until that time I had no idea what kiri-e was, nor did I know he taught it.

Mr. Okamura is the father of my wife’s good friend from high school. We visit her and her family every time we’re in Japan, and that year I brought some of my drawings with me. Her father happened to be there, and saw that a lot of the subject matter I was working on was similar to his and his students’, so he showed me some of his artwork. Ever since then we’ve met every year and he’s taught me paper cutting whenever I’m there. We also usually go on a short trip to different places with other students of his. We’re always going with the express purpose of taking pictures for kiri-e, or seeing other kiri-e artists. Again, why this all happened the way it did I really can’t say, but there’s no way I can repay him for everything he’s done for me.

What kind of contact had you had with Japan at that point?

At that point I had been to Japan twice already with my wife (then girlfriend), and had visited a number of temples and castles. I had learned Japanese language at university as well, although I was/am far from fluent. Other than that, I had read a lot about Japanese history and religion, and obviously spent hours looking at books with pictures of temples and castles.

What role does your wife have in your continuing work as a kiri-e artist?

My wife has always played a large role in my life as a kiri-e artist. There’s the obvious fact that if it weren’t for her I never would have met my teacher, so without her literally none of this would have ever been possible. She continues to support me and offer honest advice whenever I ask. She is not an artist, and that helps because she sees my artwork the same way that most of the rest of my audience will. I can usually tell in a matter of seconds without her saying anything if she thinks something is good or not. Usually this is a good predictor of how a piece will be received by other people. She has also helped a lot with reading kanji characters, which helps me to understand the history and meaning of certain buildings or places.

How often do you get to Japan nowadays? What is the kiri-e art scene like today?

I try to go every year, but it’s very expensive, so it’s becoming every other year. I still consider myself extremely fortunate to be able to do that. I’m not sure I’m qualified to comment on the kiri-e scene in Japan, but I can say that kiri-e is much, much more common in Japan than in North America. Every time I’m there my teacher takes me to see different exhibitions or shows so that I can see different ways people are using kiri-e. I’ve also been able to meet a couple of artists that are way beyond my level of ability. I always love seeing their works because it gives me something to strive for, or a new technique to try.

As you know Japan is very much a country and culture that has strict norms, and only really promotes expression in small bursts in certain contexts. If art serves its purpose it’s going to reflect the environment that created it. I suppose this style of art works well to reflect that culture, because you need to have a lot of patience and restraint, but in the end it allows you to express yourself in one solid, visual statement. With each generation, art is going to change and develop into something new, that’s inevitable. Overall from what I’ve seen, newer artists (both Japanese and non-Japanese) aren’t afraid to take this art form and really do some wonderful experimenting with it. I’ve seen a lot of works using cut paper in ways that I never would have thought of. As it grows and is used by people from different cultures and backgrounds we see a lot of new things being done.

How connected to Japan are your kids? What role has your wife had in this? Yourself?

I would say they are as connected as they could be, being born and raised in Canada. They have gone back to Japan at least once a year, every year since birth. Creating that connection is a high priority for my wife.

When they were young, we only spoke Japanese to them in the home, knowing that English would come anyways. It made things a bit difficult when they started going to school, but at this point English is their strongest language. They are both also in French immersion. I think already being used to speaking two languages has helped them acquire a third. For them, speaking more than one language is just natural.

I think that my love of Japan has helped them stay connected as well. I think the fact that they see me dedicate hours and hours towards something Japanese subconsciously makes them understand that we aren’t really forcing them to acknowledge their Japanese side just for the sake of it. Luckily, we’re also in a situation where there are many children from different backgrounds at their school, so knowing another language or not being fully Caucasian hasn’t caused any big issues.

Can you talk a bit about the Japanese/Nikkei community in Waterloo?

There are also a few second and third generation children, whose parents and grandparents are still involved in the local community association. A couple of them lived through the internment camps in British Columbia, as well as a society that was much less accepting of people from other cultures, and it’s really interesting to hear their stories. I think the children and grandchildren in these families get along fairly well because there is a shared, common experience, as well as a shared familiarity with the culture and language. As they grow older they become conscious of their place in this unique community, and that familiarity with one another creates a bond among them.

I think the connections will naturally be made stronger where they need to be.

My wife has the need to have Japanese friends, so she does. We know many families in Canada that approach their relationship to Japan very differently. Some make an extra effort to keep the culture alive in their children’s lives, some don’t. I don’t think either approach is “better” than the other, but every family is different and I don’t think this is an issue that has a right or wrong way of looking at things. At a certain point it seems to become a personal choice as children grow into adults as to how much of their parents’ culture they want to keep. If one of my children married a Canadian of European descent, and my other child married a Japanese person and lived over there, their ideas of what it means to be half-Japanese and half-Canadian would develop into something very different. I know from personal experience that this is something that affects families that come from many different parts of the world. I’ve been told it’s a real struggle for both the parents and children, trying to figure out a good way to balance two cultures.

Can you describe what you do at the CMHA?

I work full time with the Canadian Mental Health Association as a Support Coordinator. I’m part of a large team that provides support for people living with a wide range of mental health issues, and also provides resources for mental health and addictions. My main role is helping people deal with crisis situations related to mental health.

Any future plans for you as an artist? Final words?

If no one ever saw any of my art again, I’d still be spending most of my spare time doing kiri-e. My big goal in life is to one day be able to make a living solely off of my artwork, own a small gallery and just create and teach kiri-e all day. I always have an ever-growing list of projects and ideas to pursue both artistically and in terms of getting more exposure.

Over the next few months I have the display at the JCCC, I’ll be taking part in a couple of art shows/sales, and will have a display at an East Asian Festival. I was hoping to go to a Japanese festival in Chicago that I attended last year, but the timing didn’t work out, so probably next year again. I’ll also be sending some artwork to Japan to be displayed in a local show that my teacher holds for his students every year.

In terms of my actual artwork, I’ll be working on a series of pieces depicting the Japanese countryside. I’ve taken a lot of pictures over the years with no intention of using them for kiri-e, but the inspiration has come and I’m glad I have the pictures to use as subject matter. I did one of Hiroshige’s woodblock prints as a kiri-e a few years ago, and it turned out well, so I’ll be using some ukiyo-e as a guide to make these pieces. I’ve completed one preliminary drawing, and it has been a real struggle trying to plan out a paper cutting that will be different from what I’ve done in the past, but I really love the challenge. If they turn out well, I think the next progression is going to be to use the same style to depict Canadian scenery.

Thank you so much for this opportunity, you’ve given me a lot of things to think about going forward.

If I could be so bold, if anyone wants to see more of my artwork they can visit my website: www.japanesepapercutting.com; my Facebook page: Japanese Paper Cutting; or find me on Twitter: @papercutting.

If anyone wants to contact me, my e-mail is markyungblut@hotmail.com.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki