Read Part 5 >>

Stampede to Renounce

Public Law 405, authored by U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle, permitted American citizens to renounce their citizenship during time of war. Congress passed it and President Roosevelt signed it into law on July 1, 1944. This denationalization law was directed at the Japanese Americans in Tule Lake after widespread newspaper coverage of the November 1943 disturbances at Tule Lake led to “intensification of the idea that some law should be passed depriving these people of citizenship, and which would result in their ultimate deportation.”1

U.S. District Judge Louis Goodman would later outline the government’s goal of detaining and deporting Japanese Americans. In his 1948 opinion concerning the thousands of renunciations at Tule Lake, Judge Goodman found that the Attorney General had unstated objectives in passing the renunciation law: to keep Japanese Americans out of the WDC’s “critical areas” and behind barbed wire:

The Attorney General recognized that there was no constitutional means by which American citizens, not charged with crime and not under martial law could be detained by administrative, military or civil officials or upon a mere administrative determination of loyalty. The Attorney General was thus required to exercise his ingenuity to accomplish the continued detention of the citizen group at Tule Lake Camp without doing violence to the Constitution… If renunciation of American citizenship could be obtained from those in Tule Lake it was thought they could then be detained as alien enemies without doing violence to our traditional constitutional safeguards.2

One thing, however, frustrated the government’s plan for “legalizing” its continuing detentions of the so-called troublemakers at Tule Lake. The problem was that very few Japanese Americans were taking the opportunity to renounce. The WDC noted that on November 21, 1944, there were only 17 properly filed requests to renounce, and only 100 others who had requested applications.3

On December 17, 1944 the WDC announced that the Mass Exclusion order would be revoked and an individual exclusion program would be implemented,4 and the WRA announced the camps would be closed within the year. The Segregation Center was thrown into turmoil.5 Recognizing the potential dangers they faced if dumped into hostile white communities with the war against Japan on-going, inmates reacted with anger, fear and, in some cases, panic.

In the midst of the near hysteria, one bit of information seemed to offer a solution. The source of the information was the team of twenty Army officers who held hearings for male residents of Tule Lake to determine who would be permitted to return to the West coast. They asked, “Do you want to go out, or do you want to renounce your citizenship?”6 Those queries led many to infer that renouncing their U.S. citizenship would allow them to remain at Tule Lake.

Anthropologist Rosalie Hankey (Wax), the only paid Caucasian researcher of the frequently-cited book on Tule Lake, The Spoilage, noted that:

The means by which security could be safeguarded was suggested by reports that the Army officers were asking citizens whether they wished to leave camp and resettle or to renounce their citizenship… Reports of this sort confirmed the belief that resettlement and renunciation were not compatible.7

In a remarkable admission, the WDC also acknowledged the impact, as exclusion was ending, of stating the alternatives as either leaving Tule Lake or renouncing citizenship to stay put. “This action by WDC unquestionably stimulated the requests for renunciation by the remaining citizens in Tule Lake.”8 Nikkei inmates responded to the Army’s hints in a dramatic fashion the day after Christmas, Tuesday, December 26, swamping the DOJ with over 2,000 applications for renunciation.9

The next day, December 27th, seventy leaders in the Hokoku-Hoshi-dan, who were either Issei ineligible for U.S. citizenship or had applied to renounce their citizenship, were dragged out of their beds in an early morning raid and sent to the DOJ prison for alien enemies in Santa Fe, NM. Following the first group of seventy, 171 more Hokoku-Hoshi-dan members were sent to Santa Fe on January 26, 1945, 650 to Bismarck, ND, on February 11, 1945, and 125 on March 4, 1945. From December 27, 1944 to March 20, 1946, approximately 1,600 male inmates from the Segregation Center were sent to DOJ detention camps for alien enemies in Santa Fe, NM and Bismarck, ND.10 Some of the inmates were involved in the pro-Japan movement at Tule Lake, reported the WDC, but mainly “they were young males who were now shorn of their citizenship and were subject to treatment as any other alien.”11

The stampede to renounce gained momentum. Thousands in Tule Lake renounced, giving the government authority to detain them. The nagging problem of the constitutional and legal questions over continued arbitrary detention of individuals was solved.

In the midst of the stampede to renounce, a January 12, 1945 confidential letter to Dillon Myer, Director, WRA, from Raymond R. Best, Tule Lake Project Director, described the tragedy from the mass renunciations and urged that residents of Tule Lake be permitted to remain under protective custody until the end of the war. Best said that the thousands who wanted to renounce did so out of confusion and anxiety over forced departure and “irrepressible rumors that renunciation will assure them of detention and protect them against expulsion from this center.”12

In honesty, I will state that neither I nor my staff clearly understand the situation and as a result our efforts to explain it to the evacuees, together with statements issued from Washington, by the army, and appearing in the public press, have resulted in the greatest confusion in the colony. The central theme of evacuee thought at the present time is focused not on how to leave the center, but on how to remain in it. Most of the adult evacuees have given negative loyalty answers or have otherwise placed themselves in a position making war-time relocation extremely difficult. They have become emotionally conditioned to accepting the promise previously extended to them here that this camp would remain open to them as a haven during the war. They now see themselves faced with the choice of having the camp closed and being forced to relocate or in someways persuading some agency of the Government that they are dangerous and they must be detained.

The seriousness of the situation in which many citizens are being led to renounce their citizenship solely for the protection against having to relocate warrants, in my opinion, a clear and unqualified announcement that no resident will be forced either directly or indirectly out of this center for the duration of the war, and either this center or a similar center will be available to the present residents of Tule Lake on a voluntary basis whether or not they renounce their citizenship.13

Tule Lake WRA Community Analyst Marvin Opler described the renunciations in an April 23, 1945 confidential memo to Dillon Myer, advising the Administration of the rank injustice of the renunciation program:

I have found renunciants who did so in defiance of family pattern ‘because friends renounced,’ renunciants who have taken the step simply out of fear that relatives abroad would be prosecuted by the Japanese government… With mass pressures at work in the community, renunciations were neither individual nor voluntary. Parental pressures, the pressure of draft rumors, mass sign-ups and mass-applications were the order of the day. The hearing officers recognized that wives followed husbands, and children parental decisions.14

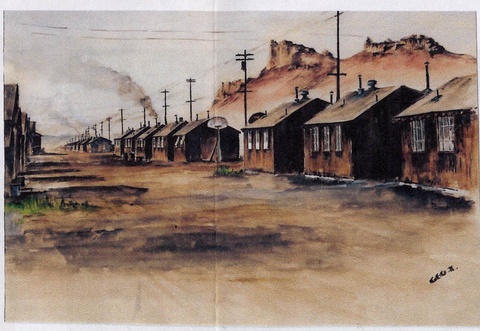

Judge Goodman, in his 1948 opinion concerning the renunciations, reflected on the conditions at Tule Lake. Giving up their American citizenship, said Judge Goodman, was “the outgrowth of the combined experience of evacuation, loss of home, isolation from outside communication and concentration in an enclosed, guarded overpopulated camp with little occupation, inadequate and uncomfortable living accommodations, dreary and unhealthful surroundings and climatic conditions—producing neuroses built on fear, anxiety, resentment, uncertainty, hopelessness and despair of eventual rehabilitation.”15

Why would someone who was penned up for years and traumatized by the terrible conditions in Tule Lake’s Segregation Center seek continued incarceration? Michi Weglyn viewed the situation as one in which “hordes of frightened, demoralized Americans sought self-imprisonment at the price of an irreparably depreciated, seemingly worthless citizenship, so great was the fear of resettlement in America.”16 The process was deceptively easy, she said. “By simply declaring loyalty to the Emperor and tossing off what amounted to a mere ‘scrap of paper,’ they could cancel out forced resettlement, rule out the draft, and extend protective custody for the entire family until such time as they could depart for safer shores.”17

Notes:

1. Supplemental Report, page 113.

2. Opinion of U.S. District Judge Goodman filed in Abo v. Clark and in Furuya v. Clark, pages 8-9. Filed April 29, 1948. 77 F. Supp. 806.

3. Supplemental Report, page 116

4. FBI Report, August 2, 1945, page 196.

“Citizens within these four categories will be served with individual exclusion orders by military authorities and it is expected that the majority of them will be kept in the Tule Lake Relocation Center which is being utilized as a segregation center for disloyal Japanese. Alien Japanese by the same standards will be interned in camps under the jurisdiction of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. …Japanese who are not considered loyal by the following standards will not be released.

- Those who have signified an intention to renounce their citizenship.

- Those who have expressed a desire to be repatriated to Japan.

- Those who when registering under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 stated they would not fight for the United States or would not swear allegiance to this country.

- Those who are considered disloyal for other reasons.”

5. Thomas and Nishimoto, pages 334-35.

6. Donald E. Collins, Native American Aliens, page 102-03, citing McGrath v. Abo.

7. Thomas and Nishimoto, Chapter XIII footnote 19, pp. 337-38. Footnote cited in Years of Infamy, Chapter XII, footnote 9, page 318.

8. Supplemental Report, page 109.

9. John Christgau, Collins versus the World: The Fight to Restore Citizenship to Japanese American Renunciants of World War II, Pacific Historical Review, Vol. LIV, February 1985, No. 1, page 6, citing Outline of Events Leading to Renunciation of Citizenship, Jan. 1954, carton 3, Collins papers.

10. Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial, Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II, 2003, Chapter 8, footnote 37, page 278.

11. Supplemental Report, page 116.

12. RG 60 DOJ File 146-54-012 Sections 1-3.

13. RG 60 DOJ File 146-54-012 Sections 1-3.

14. Weglyn, page 252.

15. Opinion of U.S. District Judge Goodman filed in Abo v. Clark and Furuya v. Clark, page 6. Filed April 29, 1948. 77 F. Supp. 806.

16. Weglyn, page 244.

17. Weglyn, page 236.

* This article was originally published in the Journal of the Shaw Historical Library, Vol. 19, 2005, Klamath Falls, OR.

* * *

* Barbara Takei will be a presenter for “The Tule Lake Segregation Center: Its History and Significance” session at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity on July 4-7, 2013 in Seattle, Washington. For more information about the conference, including how to register, visit janm.org/conference2013.

© 2005 Barbara Takei