Read Part 1 >>

How did 9-11 change your thinking of yourself as a JA? The larger JA community?

9-11 was undoubtedly a galvanizing moment for the JA community as it was for me, because the government’s response of targeting Muslim, South Asian, and Arab communities completely negated the apology, reparations, and promise that were supposed to insure this kind of injustice would never be repeated.

The event and aftermath redefined what being a JA meant to me by adding a heightened commitment to social justice.

How and when did you make the connection between 9-11 and WW2 internment?

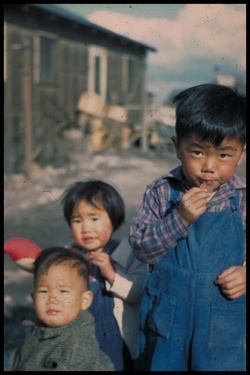

Photo taken by director Konrad Aderer’s grandfather, children incarcerated in Topaz camp (Central Utah) camp (photo by Hiroshi Takayama, director’s grandfather)

The connection between 9-11 detentions and WW2 internment hit me immediately after I saw the towers fall on TV. To me it was important to open Enemy Alien with that connection, and the antithesis: the reaction of someone who denies there’s any parallel between the two aftermaths, and what underlies that negation.

When the interviewer brings up the camps, the terrorism expert and politician Michael Wildes immediately says “we didn’t do that this time, right?” But as soon as I start probing further, he lets it slip that actually he didn’t feel it was wrong to incarcerate JAs back in 1942: “exigent times call for very strenuous reaction.”

Wildes is a perfect example of how the people who deny a parallel between the two aftermaths end up affirming it, because they’re the ones who think targeting a particular ethnic group makes us safer. Islamophobia and internment revisionism were inseparable trends in public discourse, as seen in the work of Michelle Malkin and Bush appointee Daniel Pipes. Ideological cousins of Holocaust revisionists, they say the mass incarceration didn’t really happen, but at the same time Japanese Americans really were dangerous and deserved to be incarcerated.

The parallel is much deeper than the actual policies, which were different in many ways. To try to compare them side by side as to how severe they are is educational, but at the same time I don’t believe you could make a responsible ultimate conclusion as to which was “worse.” Learning about the two eras tells us a lot about where we’ve been and where we’re going as a system of states which parcel human rights on a sliding scale and maintain their legitimacy through violence.

What is it like to be Muslim in America today?

I’m not a Muslim, so I can’t speak to what it’s like to be a Muslim in the U.S., and I wasn’t a JA during World War 2 either, so I can only imagine that experience.

Are there parallels with being JA in 1942?

There are parallels. It’s essentially the same government agencies using related tactics and laws to monitor, criminalize and incarcerate immigrant communities along with their citizen family members.

So, who is Farouk Abdel-Muhti, the main subject of your film?

Farouk Abdel-Muhti was born near Ramallah, Palestine in 1947. His mother died when Israeli Occupation forces refused to let his family through a checkpoint to reach a hospital. He came to the U.S. in the early 1970s. In the following decades, Farouk became a well-known New York City activist who worked hard for the cause of human rights at home and abroad.

What was his crime?

Farouk was arrested on April 26, 2002, in Queens, New York, by the Absconder Task Force, a joint federal-state immigration enforcement unit which targeted non-citizens from Muslim countries. But this arrest also came a month after he began arranging interviews with Palestinians in the Occupied Territories on the New York radio station WBAI-FM, making him one of several Palestinian activists arrested in that period.

Was he targeted just because of where he was from?

Was Farouk targeted for being not only an Arab, but a Palestinian? In his interrogation at a Federal building in lower Manhattan, FBI and INS officers tried to coerce him into giving names of people who had given aid to Palestinian organizations. When Farouk refused, he was knocked to the floor and methodically beaten by agents for 15 minutes.

Even the Kafkaesque, indefinite form of detention Farouk was placed in smacked of a cruel joke on his Palestinian origins. The sole legal basis for his detention was a deportation order, but because he was a stateless Palestinian, he could never be deported.

After leading a hunger strike with four other immigrant detainees, Farouk was kept in solitary confinement for eight months in York County Prison, Pennsylvania. In November 2003, guards beat and kicked him in the Bergen County Jail, in New Jersey, after finding what they called “anti-government” publications in his cell. When Farouk mentioned his human rights, one of the guards said, “you have no rights, f-----g Palestinian!”

So yes, Farouk’s arrest, detention, and the abuse he sustained was in effect a 2-year U.S. government hate crime on a Palestinian. But all the more so because he was a progressive activist who didn’t stop organizing people to stand up for themselves even in detention.

Your visit with your Nisei grandmother in Cleveland, Ohio offers an interesting juxtaposition with your visits with Farouk in Hudson County Correctional Center.

It’s when the struggle to get Farouk free is at its darkest that I drive from NYC to Ohio to visit Grandma Toyo. At that moment, Farouk has been in solitary confinement in York, PA and I’ve been denied permission to interview him.

Given that Farouk wasn’t charged with terrorism or any crime, why was Homeland Security allowed to detain him after 9/11?

Farouk was in the situation faced by thousands of immigration detainees: held indefinitely in prison, not on the basis of a criminal charge but a deportation order. Legally, a detainee can only be held for the length of time it takes to arrange his or her deportation, up until six months. After six months, according to a 2001 Supreme Court ruling (Zadvydas v. Davis), the detainee must be released. As you see in the film, Farouk was held about four times longer than that. He was impossible to deport because he was a Palestinian rendered stateless by Israel’s occupation of his homeland. I said “legally” detainees can be held up to six months, but the U.S. government detains thousands of people illegally for longer periods of time.

The INS, which became the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) over the course of his detention, lengthened Farouk’s detention by pretending it didn’t have proof he was Palestinian, even though they had his birth certificate, and repeatedly implying he was a possible terrorist threat because of his political advocacy.

© 2013 Norm Ibuki