Read “Part 6: Constant King [1 of 2]” >>

How, then, are manhood, fatherhood and hierarchies constructed in this? It’s not just one thing.

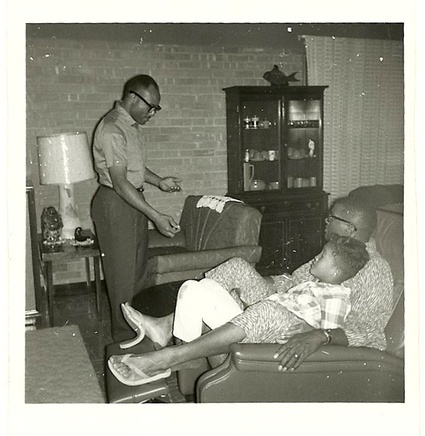

You’re too young to remember, I think. One time I was giving you a bath. It was at our house in Ōme. Your Dad came to Japan to see how we were doing, a year after he was here for your birth. We were still waiting for the American government to let us marry. Until then, your father could visit us only once a year.

I was putting you in the bath and your father came in. He suddenly sees this huge blue mark on your butt. He asked me what this was. I told him it was the mark left by his hand when he spanked you. You’d peed in your pants or something earlier that day and he spanked you. You were one-year-old, I think. When he saw the mark of his hand, he pulled you close to him and hugged you with so much tenderness. He seemed like he couldn’t believe it. He told me “never again.” And your father never hit you again, for any reason. I loved your father for that. He is a kind man. You should appreciate your father.

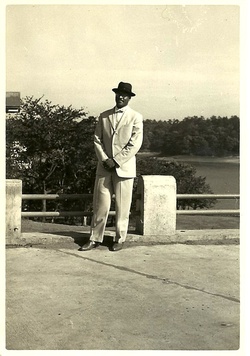

What toll does this take when sitting at the dinner table with Mama and me while he was experiencing some of the worst racism in the U.S. military bases in Korea and the U.S.? What stories of death and fire could he not tell, or even have the words for? What had accumulated from his young soldier days fighting in Korea, after battling Klu Klux Klan in Tennessee as a child, his segregation battles with racist white superiors on the bases of Japan, and later in the battlefields of Vietnam? What had become his relationship to Asians and the Pacific? How, then, did he relate to Mama and me?

When I was in my 30s, Mama told me that Dad was sent back to the U.S. after his helicopter was shot down in Vietnam and he was injured and in the hospital. Dad continued to stay in the US Air Force into the ‘70s. He wanted to rise higher in the ranks. This became possible only to a very small degree. Blacks were never promoted higher than a certain rank. Dad found out the hard way.

Against him and from somewhere over him in the hierarchy there needed a space for him to be empowered. In Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, with Asians—Dad became humanist. He had brought home Japanese American U.S. soldiers and Puerto Rican soldier friends to our home, even in the early days, understanding himself to be “humanist.” What role does marrying a Japanese woman play? Where does the violence and destruction of Asians—the constant experiences of life in Asian subjugations, go in his imagination and actions? Where would his frustrations, displacements from himself, and his growing rage go? Dad was a man of peace. He never yelled, threw things or even raised his voice or showed anything out-of-line in our house. But he dominated. Should he? Shouldn’t he? At our dinner table, how would this play out? How would Mama’s life and dreams play out? What would I become in this?

I begin a short list of notes:

- 1924 Immigration Exclusion Act or Chinese Exclusion Act (USA) targeted Asians especially

- In 1945 and 1946, U.S. Congress passes special laws for war brides, but not for Japanese brides.

- Public Law 213 allows spouses of U.S. citizens 30 days to sign all papers to immigrate to the U.S. with their American husbands, from the date July 22, 1947. Massive paperwork, investigation of Japanese women’s backgrounds, and necessary permission directly from immediate commanders prevent the majority from even qualifying.

- Frustrated U.S. soldiers petition Congress for relief. Many Japanese commit suicide, along with a few U.S. soldiers, after years and years of fighting their commanders and the U.S. government. Many GIs renounce their U.S. citizenship. Many are married through Shinto priests in Japan, even though Shinto is not recognized as legitimate during the U.S. Occupation. For the couples, it was a legitimate union until the U.S. laws changed.

- Between 1941 and 1951, approximately 200 private bills are passed to allow all sorts of controls on racial exclusions.

- June 27, 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act revokes the 1924 Exclusion act.

- Before 1952, approximately 819 Japanese brides were admitted to the U.S. Most were to Japanese American Issei (first generation Japanese Americans) who had petitioned U.S. Congress. At the time, most Issei and Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) despised any Japanese women who married U.S. servicemen and treated those Japanese women (like my Mama who came to the U.S. as late as the 1960s) accordingly.

- In 1952, 4,220 were able to immigrate. For each year, there is a quota limit established as to the number of brides allowed.

- In 1962, Mama is one of the 2,749 brides named in the immigration statistics that are allowed to immigrate to the U.S. I was already 7-years-old. Dad and Mama married only after permission was granted after 4 years of pleading and waiting with military commanders as well as the U.S. government.

In Mama’s photo album, I see one of her when she is young. She is in western style lingerie sitting on the bed with her back to me, turning her head and face to the camera with a nice smile. Toward the top of the photo, in my Dad’s handwriting is written: “To my darling Emiko, my sweetheart.”

Dad and Mama exchanged many letters while they were separated between Mama’s home in Japan while the armed forces tried to keep them separated, with Dad in Korea, then all over the U.S. They kept writing letters, encouraging each other, waiting. For Mama, especially, these were the years of hoping and dreaming, wrapped in the rapture of freedom from the confines of Japanese womanhood into a “new” history. For Dad, it was not just love, but a way to express his “equality of all humanity” internationalism.

(The End)

Note: The above statistics were taken from: Japanese War Brides in America: An Oral History, by Miki Ward Crawford, Katie Kaori Hayashi, and Shizuko Suenaga.

This is an anthropology of memory, a journal and memoir, a work of creative non-fiction. It combines memories from recall, conversations with parents and other relations, friends, journal entries, dream journals and critical analysis.

To learn more about this memoir, read the series description.

© 2011 Fredrick Douglas Cloyd