>> Read part 5

During the day, Kurihara and his fellow soldiers were occupied with bivouac and artillery practice, trench digging and mock trench warfare, bayonet drills, hiking, and marching. In their spare time they participated in team sports, took classes, and enjoyed movies and other forms of recreation. Through the War Camp Community Service, Kurihara enjoyed the hospitality of the families of Homer Knight, a physician in the nearby town of Charlotte, and William Green, president of an advertising company in Detroit. In his several visits to their homes, he was “treated like a prince.” He was deeply touched by their kindness, which helped to sustain his positive identity as an American and made him even more determined to “fight and die for the U.S.”1

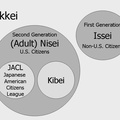

In Kurihara, the War Department was successful in its effort to “Americanize” its seemingly foreign soldiers. The Department was concerned about recruits who were immigrants and sons of immigrants, who constituted more than 18 percent of all the soldiers. This large percentage resulted from the millions of newcomers who had settled in the United States during the prior three decades. The effort by military leaders to Americanize their soldiers mirrored similar assimilation efforts across the country. In the cantonments ethnic community leaders participated in the Americanization push by teaching English, giving patriotic speeches, and translating patriotic literature and other forms of war propaganda. At the same time, they advocated successfully for the cultural and religious needs of immigrant soldiers. As a result of their efforts, for example, the military granted leaves for religious holidays and welcomed the services of immigrant clergymen. It should be kept in mind that this enlightened treatment was aimed at immigrants from Europe. American Indians, Mexicans and Mexican Americans, Asians and Asian Americans, and African Americans were not of primary concern in this effort.2

In contrast to the anti-Japanese hostility on the U.S. West Coast, and despite the increasing tensions between the Japanese and U.S. governments during the war, as an enlisted soldier in his training camp and on the battlefields of France, Kurihara experienced little or no anti-Japanese sentiment or hostile behaviors toward him. This gave him a feeling of belonging, which fed into his identity as an American.3

Figure 3. Kurihara, age 22, in World War I uniform, with unidentified man, 1917. Courtesy Grace Fukumoto.

Kurihara embraced “the hyperpatriotic atmosphere of the war, in which all were called to demonstrate their ‘unqualified loyalty.’” He further welcomed the idea of military service being “the ultimate test of a man’s Americanness.” Like other Asian Americans and like Asian immigrants, European immigrants, African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos who joined the armed forces, he was enthusiastic about demonstrating his American identity and loyalty to the United States. At the same time, he, and they, hoped to gain greater respect from the larger community and improve their groups’ social standing (figure 3).4

In France, Kurihara experienced the nightmare of war, a contrast to his training experiences at Camp Custer. Two decades later he looked back at his experiences and wrote, “Let those who agitate for war fight it out. Let them carry that heavy pack and hike to the front for days and nights without a decent meal. Let them drink the muddy water, and let them go without a bath, so the cooties can flourish on their filth! If such is not enough, let them sleep in a rat-ridden, cold and damp dugout. Let them stand guard and freeze in bitter cold. Let them live under bombardment with death staring them constantly in the face, and see if they ever will ask for another war!”5

Soon after Kurihara wrote this exhortation, America was at war again, and he found himself incarcerated by the country for which he had risked his life. Failing to recognize the patriotism displayed by Kurihara and other Japanese Americans who served in World War I, the U.S. government treated them as suspicious “alien citizens”—those born in the United States and thus U.S. citizens, “but who remained alien in the eyes of the nation.” Kurihara did not take this affront quietly, and from within Manzanar, he became a vociferous and impassioned dissident who asserted his rights as an American citizen and World War I veteran—rights he had defended with his life.6

Notes:

1. Frank Parker, “Custer begins Trench Work,” Detroit Free Press, 7 Nov. 1917; Edward Speyer, “Custer Bayonet Classes Taught How to Growl,” Detroit News, 4 November 1917; “Custer Gives Sham Battle,” Detroit News, 18 December 1917; “Camp Custer Boosts Sports for Soldiers,” Detroit News, 16 September 1917; W. J. Cameron, “Yanks Study French; Aliens Study English,” Detroit News, 9 November 1917; Camp Custer, 4; Kurihara, Autobiography, 5.

2. Ford, Americans All! 3, 14, 112-36; “Stimulating Loyalty,” Detroit News, 11 September 1917; “Draft Aliens for U.S. Army,” Detroit News, 14 September 1917; Gerald E. Shenk, “Work or Fight!” Race, Gender, and the Draft in World War One (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 119, 122.

3. While Japan and the United States fought on the same side during World War I, their national interests conflicted in the Pacific, and during the war the relations between the two countries deteriorated. See Noriko Kawamura, Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations during World War I (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2000). My statement on the absence of hostility toward Kurihara is based on his autobiography, in which he discusses both warm relations with and hostile treatment by others. In recalling his experiences during World War I, he mentions no ill treatment by fellow soldiers or officers and only warm feelings toward families in Michigan who befriended him.

4. Lucy E. Salyer, “Baptism by Fire: Race, Military Service, and U.S. Citizenship Policy, 1918-1935,” The Journal of American History 91 (Dec. 2004): 848; Britten, American Indians in World War I, 124, 130.

5. J. Y. Kurihara, “I Was In The War,” Kashu Mainichi, 19 May 1940, 26 May 1940.

6. The phrase “alien citizens” comes from Mae N. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 8.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society