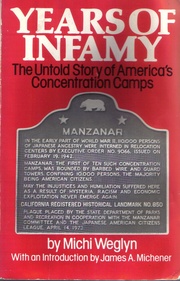

Like it was yesterday, I remember the first time I picked up and started to read Michi Nishiura Weglyn’s Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps. My now-faded, coffee-stained, first-edition William Morrow copy is dated 1976, so I must have gotten it shortly after it came out. After reading the first several chapters that gave a moment-by-moment description of the events leading up to the decision to incarcerate and Roosevelt’s EO 9066, I was dumbfounded. Never before had I read such a thorough, detailed account of why American citizens of Japanese descent were rounded up and put into concentration camps. I couldn’t help wondering then, “Who in the world is this woman with the German-sounding name of Weglyn1, living in a Nisei vacuum on the East Coast, and—of all things—a costume designer!”

Secretly jealous of her ability to produce such a history-changing and mind-boggling book, I was dying to know more about this woman named Michi Weglyn. Sadly, with no Google to turn to, I resigned myself to knowing only that there was a costume designer in New York who did what no Nisei before her had done. In doing the research and the writing, she not only pushed the gas pedal to start the redress movement, she also changed the way we as Japanese Americans look at our history, our government, and most importantly, ourselves.

Having just completed a brand new website (www.michiweglyn.com), the first complete web offering on the life and work of this complex and dynamic woman, little did I know that I would get to know Michi Nishiura Weglyn almost better than I knew myself. Funded by the California Civil Liberties Public Education Project, I spent the last year going through box after box of photos, books, and papers that were left in storage for ten years after her death in 1999. They were untouched since her rent-controlled New York City apartment was cleaned out shortly after Michi died by a friend who told me that she was overwhelmed when she saw the job that packing would involve. Those who knew Michi remember her as one who saved every article, every newspaper clipping, every source that might be of value to someone, somewhere, in her never-ending search for the truth about what happened during World War II. And, not only did she save everything, she made multiple copies of each. She had detailed notes scribbled everywhere, pieces of papers cut-and-pasted together—all in seemingly disorganized fashion, but with a method that probably only Michi herself would know. It was this array of material that I had the opportunity to see when the boxes containing Michi Weglyn’s life’s work arrived on my doorstep. You can imagine my dismay.

However, as I slowly looked through the material in hand, I felt so fortunate to be able to take my perch looking back at a life of almost maniacal dedication and determination. I realized that these qualities were essential to write a book of the magnitude of Years of Infamy. And I began to understand why this work was to become the only book that this brilliant, driven woman could muster. I saw why it took her eight years to do the minutely detailed research, and why no other subject would grab her attention in the same way.

Indeed, there were other subjects that Michi pursued with the same passion that she used for Years of Infamy . Within these boxes were volumes of material on Pearl Harbor, a subject she intended to pursue as her next masterwork. She also had an abiding interest in Japanese haiku written in camp, as seen in the reams of material written on the subject found in her files, as well as actual poetry gathered over a series of years. Sadly, neither of these topics was made into a published work bearing Michi’s byline.

Those who knew her best remember the papers that were strewn everywhere in her one-bedroom apartment—from inside the kitchen oven to kitchen cabinets and drawers, to the crevices of her bedroom—which represented the work she did not want to leave unfinished. At the end, she even worked from the living room in a rented hospital bed now laden with paperwork, after having moved her sleeping quarters in her not-so-spacious apartment.

Though it is impossible to capture the essence of the woman who can be described immodestly as our redress champion, our feminine knight in shining armor, our Rosa Parks—it is hoped that reaching out on the web about her life and work will be an inspiration to all those who think that it is impossible for one person to make a difference. Hopefully, www.michiweglyn.com will offer some insight into how this single-minded, unwavering, and courageous woman helped erase the shame that was a part of our history, and turned it into a lesson in civil justice.

Notes:

1. The original 1976 version of Years of Infamy did not include Weglyn’s middle name of Nishiura. The cover and title page simply read, “by Michi Weglyn.” It was at the urging of activist Edison Uno that the publisher changed her byline to include her Japanese surname.

* * *

Film Screening & Panel Discussion

Out of Infamy: Michi Nishiura Weglyn a film by Nancy Kapitanoff and Sharon Yamato, narrated by Sandra Oh

Saturday November 7, 2010 at 2 pm

Japanese American National Museum

This short film paints a portrait of her dynamic personality and gives a stunning human face to the struggle for civil justice. The film recently received a Special Jury Mention at this year's Tribeca Film Festival. After the film, there will a special panel discussion featuring, Sharon Yamato, Nancy Kapitanoff, and Professor Art Hansen.

© 2010 Sharon Yamato